Pilot program carried out 26 years ago proves good for demographic structure, Duan Yan in Shanxi and Shan Juan in Heilongjiang report.

When Wang Wei works his night shift at a steel plant, his wife Chen Aihua can tend to the housework without having to entertain their 8-year-old son.

The boy can, instead, play with his little brother thanks to a policy implemented 26 years ago.

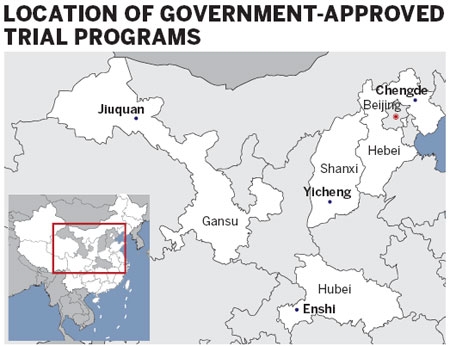

The family lives in Yicheng county of North China's Shanxi province - one of the four regions that the central government chose in the 1980s to test a policy allowing two children in rural families.

|

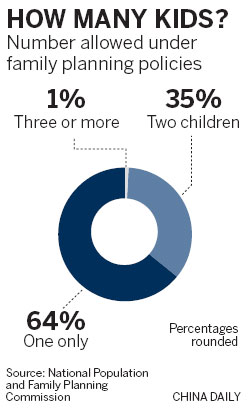

Ethnic groups and families in remote border areas can also enjoy the two-child policy.

Demographic indicators in these special zones have turned out better than the national average, and they have provided valuable references for China's family planning policy, according to Gu Baochang, professor of demography at Beijing-based Renmin University of China.

A 2005-2007 study that Gu led found that a two-child policy is both practical and better for healthy population development.

It is also true in the eyes of a mother.

"Two is better than one," Chen said as she held her boys beside her in their sparsely furnished home.

"They've even learned to share their toys."

|

"We have to consider the economic situation when it comes to having babies," Tian Xiuju, 30, said while watching her 2-year-old son in the early education program that is provided, free, by the local family planning department.

A mom of two now, Tian said that if her firstborn had been a boy she wouldn't have had the second. "Many in the village of around 200 people choose to have only one today."

Like most others who live in Luoguhe, in Northeast China's Heilongjiang province near the Russian border, Tian isn't interested in having a second child, as is allowed.

Many in Yicheng have enjoyed a similar policy, but 8,430 households (about 12.5 percent of those eligible) have waived their rights to a second chance at parenthood.

Liang Rongrong, 28, is caring for 5-year-old Liang Zhenjiang while her husband works in Guangzhou, in South China. Burdened with medical bills for her son's cardiac surgery - 30,000 yuan ($4,730), equal to the family's average yearly income - Liang said she could not afford another child.

"Taking care of my son is our priority."

Fears unrealized

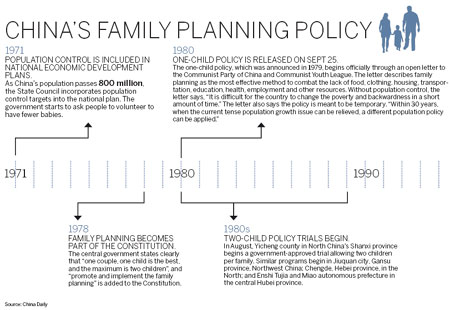

In 1985, when most couples were allowed to have just one child, demographer Liang Zhongtang noticed the conflicts when villagers' desires for fertility clashed with the national policy.

Liang was a teacher at the Party School of Shanxi Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China then, and he suggested to the central government a "second-child" pilot program, but with strings attached.

China's marriage law, then and now, sets the minimum marriage age at 20 for women, 22 for men. Under Liang's proposal, women could not marry until they were 23, men at 25. Women could have a first child at 24 and a second at 30.

Local cadres worried that a relaxed family planning policy would lead to a quick and explosive increase in population. It didn't happen.

Two decades later, population is growing slower in Yicheng county than the average for all of Shanxi province. In 1985, Yicheng had 258,000 residents, 1 percent of Shanxi's total. In 2007, the county had 316,000 people, 0.92 percent of the provincial population.

"If the law allows people to get married (and start having children) at 20, within a century there will be five generations of people. By delaying the childbearing age for four years, there will be only four generations of people," explained Wu Baotang, director of Yicheng county family planning bureau.

More important, demographic indexes turned out to be more balanced than the national average. Statistics from Wu's bureau show that 104 boys are born for every 100 girls in Yicheng. The national average in last year's census was about 118 boys to 100 girls.

Unlike Yicheng, where couples need to wait six years to have a second child, the policy in Heilongjiang's border area lets couples set their own timetable.

"Population growth and development in our two-child policy areas appear to be more healthy than the general situation of the country," said Jia Yumei, the family planning chief for the province. And there has been no significant increase in the total fertility rate, the number of children a woman has during her lifetime.

"People's desire for reproduction has kept weakening here," she said, "and some places in our province, like the Greater Hinggan Mountain area, have seen negative population growth for several years."

|

|