Morphine is culturally a tough medicine

Deeply ingrained fears

However, despite the huge progress, Xu said he has no illusions about the scale of the problem in China. Among the multiple hurdles still to be overcome, the deeply ingrained fear expressed by patients represents the initial obstacle.

Yan Runlan has first hand knowledge of this. Lying in bed in the oncology ward of Beijing's Aviation General Hospital and fully aware of her situation, the 67-year-old, who has terminal stomach and colon cancer, balked not at the inevitable outcome of her illness, but at the two small morphine tablets on her bedside table.

"There will come a day when I'm standing right on the doorstep of death and experiencing debilitating pain - I want to save all my morphine quota for that day," she said. "If I start to take it right now, I might become addicted before that moment arrives."

|

|

|

|

Liu Yin, Yan's attending physician and the director of the oncology department, has seen many similar reactions: "It's not uncommon for patients to hide the morphine pills they've been prescribed, sometimes abetted and assisted by their equally concerned relatives. The thought of an undignified death as a drug addict tortures them."

In the darkest and often most-neglected corner of a dying man's heart, psychological terror has a much firmer reign than physical agony. Physicians, with their immense sway over patients, are often blamed for not tending to that corner, not always for the wrong reasons.

Ning Xiaohong, an oncologist and palliative care expert at Peking Union Medical College Hospital, said that the strong, yet often subconscious, resistance to morphine use among Chinese doctors is something closer to the heart of the problem.

"Sadly, many of our so-called health professionals are themselves unwitting believers of the addiction theory," reflected the doctor. "By withholding a definite answer when questioned by a concerned patient, and by not providing proof convincing enough to dispel the doubts, a doctor could actually serve to reinforce the patient's existing fears."

This is aggravated by a strong tendency among Chinese doctors to trust no one but themselves.

"They believe that they are the only ones in a position to judge whether a patient is suffering sufficiently to qualify for morphine administration. In most cases, decisions are based purely on 'subjective evaluations' - various figures yielded by clinical tests pointing to a specific stage of the illness," said Ning. "The WHO has long deemed this approach arbitrary and obsolete."

One concept she emphasized is "Total Pain", that is, the sum total of a patient's physical and psychological suffering, which is usually much higher than the former alone. "Depressed and inconsolable, a cancer patient routinely feels a level of pain that would be theoretically associated with a still-to-come stage of their disease," said Ning. "Not many Chinese doctors have a deep understanding of that."

The underestimation of pain could lead directly to the under prescription of morphine and other analgesics, as desperate patients are urged by their omniscient doctors "to be strong".

Cruel as it sounds, to put the doctors alone on trial would be to tiptoe around the very core of the issue, which lies with the management, from the various levels of local government all the way down to the leadership of each and every hospital.

"In China and many other countries, the sale, purchase and consumption of morphine for recreational purposes are all crimes punishable by imprisonment. While the government has correctly taken a very strong stance against all possible flows of morphine into society, it has to work equally hard to meet the urgent needs of those whose pain cannot be alleviated without it," said Liu the oncologist. "The reality for the moment is: Although the Central Government is unequivocal in its message, the seismic waves for change lose much of their power in hospitals situated a long distance from Beijing."

Twenty years ago, an outpatient could ask the doctor for a prescription of morphine that would last a maximum of three days. However, in 2002, the Health Ministry extended the number of days to 15. Even today, only half of all Chinese hospitals act on that standard. For doctors, this passive approach amounts to effective discouragement.

"For every morphine pill given to a patient, especially an outpatient, there's a possibility - although this very rarely happens in reality - that it will find its way into the hands of someone else," said Liu. "When this does happen, there's bound to be a police investigation. And it appears to me that some health officials are simply more interested in holding onto power and staying out of trouble than reducing the toll that cancer pain takes on its victims."

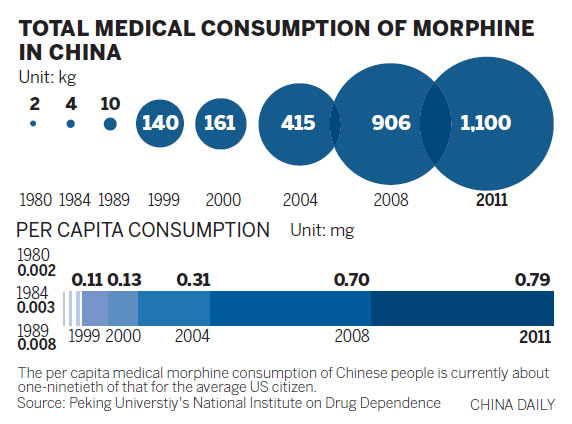

According to Liu, even with the 2011 figure of 0.79 mg per person, China still ranks just below 100 among the more than 120 countries that have submitted their numbers to the WHO, which considers it the foremost indicator of a nation's pain relief effort. And the per capita medical morphine consumption of Chinese people is currently about one-ninetieth of that for the average US citizen.

Twenty years ago, Liu was running a first aid training class for students from neighboring Southeast Asian countries. One day, the victim of a car accident was rushed to the hospital, bleeding and groaning. While all the Chinese staff were busy chasing up various pieces of medical equipment, a young Pakistani intern was making wild gestures and shouting out in his weirdly accented Chinese, "Morphine! Morphine!"

"His voice has stayed with me ever since," said Liu, "not because of what he said, but because of his willingness to feel so much of the pain that the injured man must have felt."

Contact the writer at [email protected]

- China issues first white paper on traditional Chinese medicine

- China's Alipay takes root in Lapland, near the Arctic Circle

- Snow sculpture 'Love Song' to be displayed in NE China

- Xi urges more reforms to give people greater sense of gain

- Shanghai urges Apple to handle recent iPhone combustion incidents