A choreographed 'dialogue' on perception, history

|

Chinese choreographer Yin Mei [photo by Peggy Jarrell Kaplan]

|

When Chinese choreographer Yin Mei first arrived in New York in 1984, she discovered the simple pleasure of peering up at windows on nighttime walks around Manhattan. She pictured the lives of the people who lived inside, and imagined wildly divergent narratives.

"Those windows and the city itself seemed to open their arms to me," Yin said. "It was an incredible feeling. When I first came to the US, my jaw was constantly dropping."

Fashions she had never seen were draped on a variety of body types and skin tones; everywhere she looked she found surprises. In China back then, everyone was the same, dressed in uniform grays and blues. The idea that everyone could be free to look completely different was a revelation.

Yin has lived in New York for almost three decades, but her work continues to be shaped by her years as a dancer for the People's Liberation Army and various troupes during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), and her discovery that the Chinese perspective was only one of many.

This weekend, the Asia Society presents Dis/Oriented: Antonioni in China, a new piece by Yin that explores her memories of the revolution in "dialogue" with Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni's once-banned 1972 documentary Chung Kuo, of which excerpts will be screened. (The movie was shown publicly for the first time in China in 2004, at a festival hosted by the Beijing Film Academy.)

Dis/Oriented, which features Yin and dancers Fei Bo and Dia Jian, was conceived as a "window" into the variety of gazes that can shape perspective, she said.

"I kept thinking and going back to this idea of windows. When your mind's eye is open, those paths open and your thoughts travel. This is a dialogue with Antonioni, but also ultimately a dialogue within myself."

The documentary, shot over eight weeks at Chairman Mao Zedong's invitation, was intended to "present a large collection of faces, gestures, and customs," according to voice-over narration. Antonioni's stark scenes of rural poverty, gritty living and working conditions, and unflinching depiction of life at the time quickly drew a government ban.

Yin, who in the early 1970s spent several months in the countryside with a state dance troupe, was one of many young people of her generation who protested the "counterrevolutionary" film. Although very few people had actually seen the movie at the time, it was common knowledge that Antonioni had humiliated the Chinese people, she recalled.

Years later, she saw the film for the first time and sat transfixed, she recalled.

"I was completely mesmerized," she said. "Most of the scenery he was filming was so real. But Antonioni was from Italy, and at the same time he had no idea what the real China was either. It was two perspectives that at the time could not speak to one another; back then, there was this idea that you are either my friend or my enemy, and nothing in between."

She began thinking about choreographing a piece that might allow for "dialogue" between the film and her own memories of the time it chronicled. But as she worked on the piece, even that dialogue began to change, she said.

"This work isn't really about Antonioni," she said. "This piece is about perception, a gaze — whether it's Antonioni's gaze at a Chinese man or, now that I'm older, my own gaze looking back at my life and my history."

Hansol Jung, director of Dis/Oriented, recalled Yin's first words to her upon meeting to discuss the work.

"She told me she's constantly seeing different realms of reality," Jung said. "She's always 14, but she's also always present. The way her mind works is fractured. This idea of perspectives and gazes, the ways you can look at a thing and the ways in which being looked at can change a person, are really important in her choreography. This piece is less about the social events of that time and more about how these stories have been instilled in her."

Dis/Oriented is about a time that was defined by a particular juxtaposition of East and West, said Rachel Cooper, director of global performing arts and special cultural initiatives at the Asia Society. While China might be viewed as a sophisticated country today, it is only as a result of China's opening-up that that old paradigm has faded, she said.

But the piece shouldn't be interpreted as overtly political, she said. "The question is, How do you understand yourself when you're in the midst of these huge social and political dramas? She was just a young girl, learning how to dance. At the core she was just trying to grow up, and there's something very poignant about that question of what it means to be a whole person."

The idea of a public persona in contrast to a private one is particularly interesting in light of the ban on the film. Antonioni likely interpreted the footage very differently from the way in which it was perceived in China, Cooper said.

"The things [Antonioni] thought were noble or moving, were read very differently in China, and that happens when you work across cultures," she said. "Sometimes you don't think about what it means in a different cultural context: Whose eyes will be looking at the work?"

The performance, which also features puppets and a live soundtrack created and performed onstage by composer Bora Yoon, is an attempt to ask questions about the meaning of love and our everyday struggles, Yin said.

"While this isn't an answer to those questions, I'm just saying that, yes, maybe this is a window we can go through to go somewhere else, to maybe feel life differently in this moment," she said. "I don't want to make a big deal about my story, because ultimately life isn't a big deal. It's just small moments."

Today's Top News

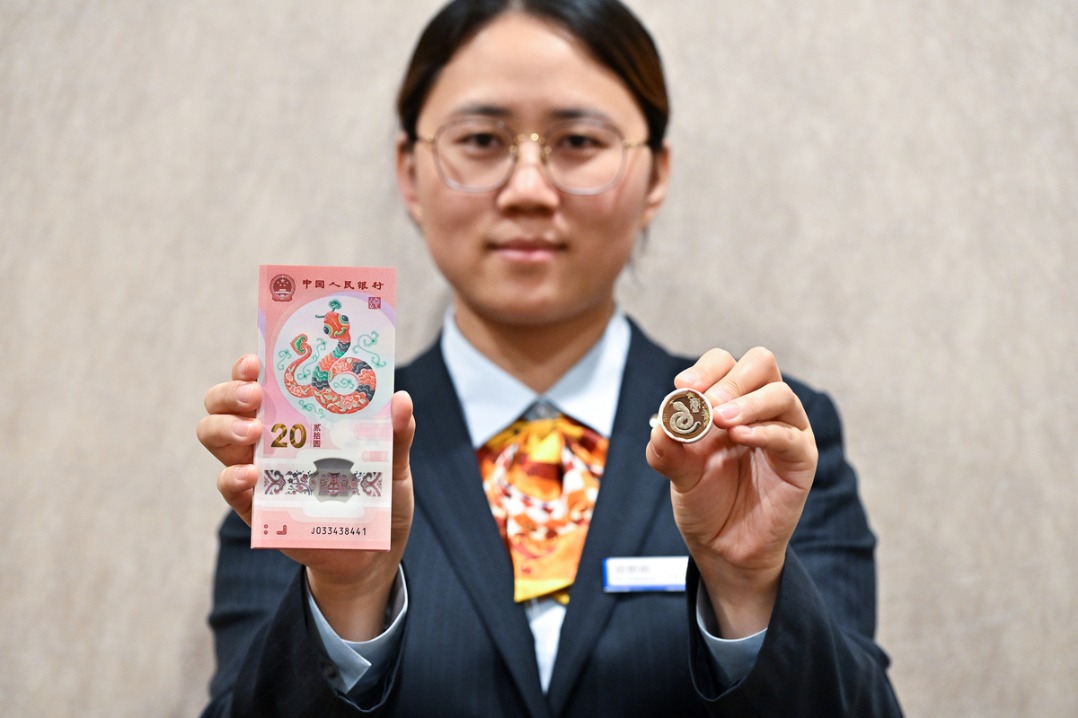

- China's central bank outlines monetary priorities for 2025

- 8 killed, 15 injured in market fire in North China's Hebei

- IoT new engine of socioeconomic development

- Visit highlights strong ties with Africa

- Xi sends congratulations to new Georgian president

- No letup in battle against corruption