Fighting back with venom

|

| A view of Nongjing village, Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. Photos by Zhang Li / China Daily and Provided To China Daily |

As China aims to eradicate poverty, residents of a rural pocket in the country's south breed scorpions for livelihood support

Amid the green vegetation on the outskirts of a small town in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, a dirt track leads to a village in a valley, molded in karst landscape.

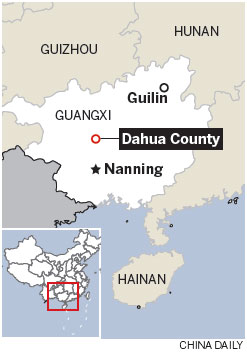

The Yao ethnic group is the dominant population in Nongjing and a few neighboring villages that are three hours or so by road from the autonomous region's capital Nanning. And while southern China is largely associated with affluence, some of its rural pockets have yet to ascend the development graph.

In Guangxi, 3.41 million people still live in poverty.

But Nongjing has recently found a fascinating way to enhance the livelihoods of its nearly 60 resident families - breeding scorpions.

As China seeks to end absolute poverty by 2020, such projects are expected to help the affected both have short-term earnings and build on entrepreneurial skills for later use.

China's poverty line is measured at the annual household income of 2,300 yuan ($335). By this 2010 standard, the country's impoverished population stands at 43.35 million, data show.

In March, the central government's work report said 12.4 million were lifted out of poverty last year. Financial aid for poverty reduction programs has exceeded 100 billion yuan.

Hu Angang, an influential economist from Tsinghua University, says China is meeting poverty reduction targets ahead of its Five-Year Plan schedules. He predicts that by the end of the decade, households in the country will be identified for assistance on the basis of their minimum insurance coverage.

Nongjing's scorpion farm, established with a government fund of 1 million yuan in September, now employees 10 locals on a full-time basis and several others for part-time work, including four women, Qiu Xiaojun, a 34-year-old civil servant, says. He has been deputed by the Guangxi government to oversee daily operations at the site.

"Once trained a person can earn between 2,000 and 3,000 yuan a month here," Qiu says. "We are providing the villagers with an income source as well as technical knowledge so that they can set up their own businesses in future."

|

| Lan Tianting, a local, works at the farm, where scorpions are bred as part of Guangxi's poverty alleviation program. |

Pharma and food

More than 2,000 people live across 10 villages in the vicinity. The residents raise pigs or poultry and grow corn mostly for personal consumption as they have little access to markets from such a remote area. Besides, the topography allows crop farming only to an extent and groundwater availability is scarce.

In Nongjing, Mesobuthus martensii, aka Manchurian scorpion, is among the main varieties bred artificially. Found in China and other parts of East Asia, where moisture levels are sufficient, a full-grown arachnid is 6 centimeters long and has sharp pincers and a deadly telson.

A female is usually larger than a male and natural breeding can take two years. But the process is completed in a few months on the village farm.

Qiu says, this year, the farm expects to make more than 1.5 million yuan from sales. The current market price for a kilogram of scorpions is 930 yuan. Nongjing is looking to meet the demand in the provinces of Guangdong, Henan and Shangdong, where the bulk of the arachnids will be sold for pharmaceutical purposes.

Scorpion toxins are used in traditional Chinese medicine to "smoothen the flow of blood in the human body". The arachnid is also eaten as a snack.

"The community is working together on this project. We want to build a brand around it," says Lan Tianting, 25, whose one job is to segregate female and male scorpions.

Although most of his peers work outside Dahua, the county where the village is located, Lan says he returned in the hope of a rise in local employment. He attended college in Guangxi's touristy city of Guilin. His 42-year-old colleague, Meng Zhiyao, despite holding a different background, seems to share Lan's enthusiasm for the project.

Meng, who spent much of his youth in poverty, says he has applied for low-interest housing loan since he started to work here. He has six children and an elderly mother to care for.

Huang Jing, a senior county official, says farms to raise cows and bamboo rats have also been built in two other villages where poverty alleviation is being targeted. Last year, 15 million yuan was set aside by the local government to supplement livelihoods in at least six such villages, he adds.

Of the county's 460,000 people, some 80,000 live in poverty, according to another official.

|

| A Manchurian scorpion that is found in China and other parts of East Asia. |

Drilling wells

As it snakes around a peak, a path places the village in full view. Rainwater harvesting is an essential part of life in Nongjing that has struggled with groundwater sources for decades. The area is said to have water trapped in aquifers but extraction has proved difficult in the past. In addition, the mountain rocks often crumble like chalk.

After a failed attempt to drill a well, authorities have decided to dig deeper - at least 280 meters below - in pursuit of water this time. A team of four engineers from a Liuzhou-based company in Guangxi has pitched a tent on a desolate cliff since November, looking to accomplish the mission through rain and wind.

A road along 11 kilometers will be constructed to connect the area's villages, says Qiu, the official from the scorpion farm.

In Nongteng, a village of nearly 30 households situated downhill from Nongjing, the county government is encouraging tourism to boost incomes. A few cottages have been painted in blue and red to draw city dwellers keen on experiencing the quiet countryside. Lan Fanglin, 33, says at her hotel, a room's rent is 80 yuan a night. She calls the business profitable.

But Wei Yuguan, a 48-year-old former plastic factory worker in Nanning, who has managed a neighboring hotel since 2015, says her property sees very few customers.

An orchard in the county's Duyang town offers an example of private-public partnership in poverty reduction in this part of Guangxi. In the past three years, oranges from this joint venture have been sold to retailers in Beijing, the city of Shenzhen and the provinces of Qinghai and Shangdong.

"A casual worker can make 70 yuan or more a day," the town's mayor Luo Yuehua says, adding that dozens of families are involved in the orchard business.

Tang Xiumei, 50, finds watering orange trees easier than her previous wood-factory shifts for 80 yuan a day. And, Huang, a 60-year-old woman who gives a lone name, expects her annual income of 2,800 in 2016, to increase with her new job this year. Her daughter's death has left her to fend for two grandchildren. Her work profile is similar to Tang's at the orchard.

Guangxi spent 18.7 billion yuan on poverty reduction projects last year, with emphasis on activities ranging from industrial programs to trade enhancement with neighboring country Vietnam, which lies to its west. Some patches of rural Guangxi have remained underdeveloped for long, in part due to regional disparities in growth.

"But the aim is to get there by 2020," Zhu Youkui, the chief economist for the local government's poverty alleviation unit, says in Nanning.

|

| Qiu Xiaojun, an official, holds up a jar of "scorpion drink". |

Post-2020

In the next three years, the central government is likely to focus on poverty reduction in the places most needed, namely the provinces of Guizhou, Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu.

Economic disparities among regions had peaked in 2004 but have declined since due to the movement of people from villages to cities for work and the adoption of measures such as the Western Area Development program, Hu, the economist from Tsinghua University, tells the newspaper in an interview in Beijing.

The dean of the Institute for Contemporary China Studies at the elite university, describes himself as a "scholar of the era following Deng Xiaoping" in a book on China's rise.

"By 2020, China will abandon the concept of absolute poverty and we will use low-income or minimum insurance to define this," he says. "It also implies that when China enters the high-income stage, the new standard will give us a better idea of how we can invest in human capital and help poor people improve their development ability."

Today, there are between 60 and 70 million people with minimum insurance in China, accounting for about five percent of the total population, he adds.

The minimum rural and urban insurance sums vary from province to province but are required by law to cover basics such as medical or pension allowance. For Guangxi, which is on the lower side of this spectrum, the figures are 300 yuan a person a month in the cities and 140 yuan in the villages. In 2015, Shanghai's minimum insurance was 790 yuan.

Zhang Li and Liu Yixi contributed to this story.

|

| An employee of a Guangxi-based company at a drilling site. |

|

| A woman from Nongjing village in Guangxi separates male and female scorpions at the farm for the arachnids. |

|

| The semi-urban Dahua county where the village is located. |

|

| A path snakes up a peak in the village. |

|

| Tang Xiumei, who works at an orange orchard in nearby Duyang town, says she finds watering the plants easier than her previous factory work. |