Mountains, temples & jungle

Famed for its majestic snow-capped peaks, Nepal also offers up a diverse array of attractions, from temple walks to treks through its lush forest wildernesses

It took my breath away when I first caught sight of the snowcapped peak of the world's highest mountain emerging from the clouds outside my plane window.

Qomolangma, or Mount Everest, is as white as the clouds. Only its sharper edges distinguish the peak itself, letting mountaineers know it's there - the highest point on Earth.

And it also tells me that my trip to Nepal has just begun.

| From left: A shop sells carved wooden Buddhas; gharial, an endangered native crocodile species; the Pilgrims Book House in Thamel. Photos by Xing Yi / China Daily |

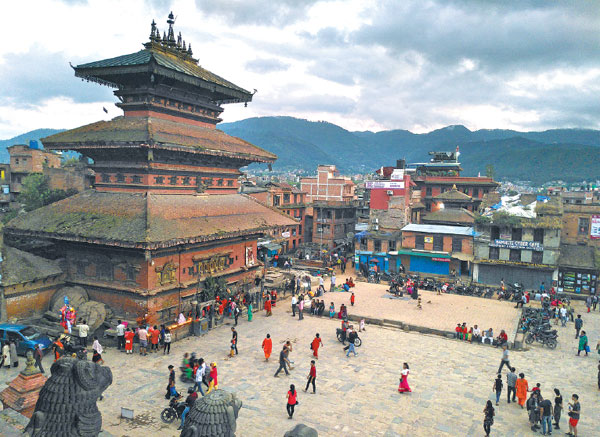

| Temples in Kathmandu can be found on street corners, in markets and squares, or even at construction sites. Xing Yi / China Daily |

As the plane begins its descent, Nepal's sprawling capital Kathmandu comes into view, occupying a wide valley on the southern edge of the Himalaya Mountains.

Dusty, chaotic and bustling on a truly metropolitan scale, Kathmandu Valley is the country's largest urban area where more than 6 million people live in a cluster of satellite cities and towns surrounding the capital.

A stroll around the city

What impresses me first of all is the ubiquitousness of Kathmandu's temples.

They come in every size imaginable and appear in almost every corner of the old city. They can be as small as a miniature stone carving set into a concave hole in the wall or a religious sculpture placed on an altar, or as large as a pagoda sitting on a huge stone base resembling a Mayan pyramid.

Rarely walled, temples in Kathmandu can be found on street corners, in markets and squares, or even at construction sites, where people pass them as they perform their daily routines - chatting, playing, resting, doing business, or simply getting from A to B.

The lines between Hinduism and Buddhism are so blurred in Nepal, and it's often difficult for outsiders to distinguish between them.

On our first morning our guide Bipin Banepali, an indigenous Newar from Kathmandu, led us on a walk from the city's main tourist district in Thamel to the old royal palace in Durbar Square, which is still being reconstructed after being damaged by the destructive earthquake of 2015.

As we walk around the labyrinthine alleyways, we bump into local people engaging in morning prayers at these temples.

Carrying plates with small offerings such as rice and flower petals, they visit temples with one and another. At each altar, they sprinkle offerings, touch sculptures of the gods with vermilion-red powder, and lower their heads while murmuring a string of prayers.

Along the road, street vendors and shops sell cashmere scarfs, carved wooden Buddhas, and singing bowls - a Buddhist meditation instrument that chimes when you roll a wooden stick around its rim.

As well as Nepali cuisine, restaurants along the way offer Chinese noodle dishes and buffalo steaks.

I opted for a thali, a generous meal served on a bronze platter, consisting of curry, vegetables, rice, and lentils served in individual bronze bowls. And throughout my trip, a cup of local herb milk tea, or Masala tea, continued to be my drink of the day.

The Pilgrims Book House in Thamel is home to one of the most complete collections of works on the Hindu and Buddhist religions, as well as range of detailed mountaineering guides.

Other than Thamel, other popular attractions include UNESCO world heritage sites such as Dubar Square, Boudhanath Stupa, or simply "Big Stupa", where we see Nepal's largest Buddhist domed pagoda, and Swayambhunath, or "Monkey Temple", which sits atop a hill west of the city, and, as its nickname suggests, is home to hundreds of monkeys.

While enjoying the panorama of the Kathmandu Valley at Swayambhunath, Banepali told me a legend about the formation of the valley.

It goes that in ancient times, the valley used to be a big lake, on which floated a beautiful and magnificent lotus.

Manjusri, the bohddisava of wisdom in Buddhism, once visited the valley from China, and seeing that the valley would be made a good settlement for people to worship, drew his sword and sliced a gorge. Water drained out of the lake, leaving the valley in which Kathmandu now lies, and the lotus transformed into a hill and the flowers became the Swayambhunath.

A walk in the jungle

The jungle is my next destination, which stretches in Nepal's southern Chitwan district.

The name Chitwan means "the heart of forest" in the Nepali language, and the district established the country's first national park in 1973 to protect its abundant animals and forests, which was listed as a world heritage site by UNESCO in 1983.

It took me 7 hours by bus from Kathmandu to reach a local Tharu people's village by the jungle, where a river separates it from the forest.

A wooden plaque in front of the resort I stayed at read: "Into the Wild".

With a group of around 16 tourists, we set off at 8 am the next morning from the river bank.

We boarded a wooden canoe and set off westward following the current of the river.

At the front of the canoe stood a local boatman with a long pole, and at the other end a boatman with an oar.

The current was fast and the river was quiet, and I could only hear the sound of the water as the boatmen paddled.

As we passed, we saw birds resting on sand banks in the middle of the river. A rhino was later spotted standing in the shallow water on the southern bank of the river bordering the jungle.

In about one hour, we arrived at Kasara entrance of the Chitwan National Park.

We first passed an army barracks, and then visited a crocodile breeding center to see gharial, an endangered native crocodile species found in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent.

We then started our jungle walk.

Our guide's name was Chok, a man in his early 60s with 35 years of experience of working in different nature preserves.

"The most dangerous animal one can encounter in Chitwan is a rhino", he said. "There are some 500 rhinos here". Rhinos are herbivorous, but will attack humans if they get too close.

People still hunt rhinos for their precious horns, so they are now aggressive toward humans, Chok explains.

But so far the jungle seemed pretty tame, and a far cry from the thrill of jungle adventures such as Tarzan or Jurassic Park.

For most part of the journey, we just walked in a line on a narrow path on the edge of the jungle.

We saw some deer, birds, and a wild gharial crocodile swimming in the river.

But at one turning over a brook, Chok stopped and motioned to us to be quiet. Then we heard splashes of water coming from behind thick shrub.

A few steps later, I saw a gray shadow pass through the dark green grass to my right about 10 meters away, then disappear quickly into the forest before I could make it out.

"A rhino?" I asked.

"Yes, it's a rhino," Chok said.

"It didn't attack us. It ran away because we outnumbered it."

Maybe, millions of years ago, we human beings came from the jungle. But now humans are intruders in it. That's why wild animals all hide away when they hear human noise.

After this, increasingly dense foliage prevented any attempt by us from entering the jungle again, and we returned to the canoes.

| A local house of Tharu people village by the jungle in Chitwan. Xing Yi / China Daily |

(China Daily 10/28/2017 page17)