China’s Active Year of Diplomacy in 2017

The article was first published on chinausfocus.com on Jan 2, 2018. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

In his landmark speech to the 19th Party Congress in October, China’s president and leader Xi Jinping boldly asserted China’s claim to being a global diplomatic power. Asserting 26 times that China was either a “great power” or a “strong power” Xi staked out new ground in Chinese diplomacy. Gone is any pretense to “biding time and hiding brightness,” as Deng Xiaoping had counseled. Instead Xi laid out a vision for China to “play its part as a major and responsible country” and “promote a community of shared future of mankind.” A significant part of his “great rejuvenation” is for China to establish a central position in world affairs. The past year of 2017 was indicative of China’s new proactive position in international diplomacy.

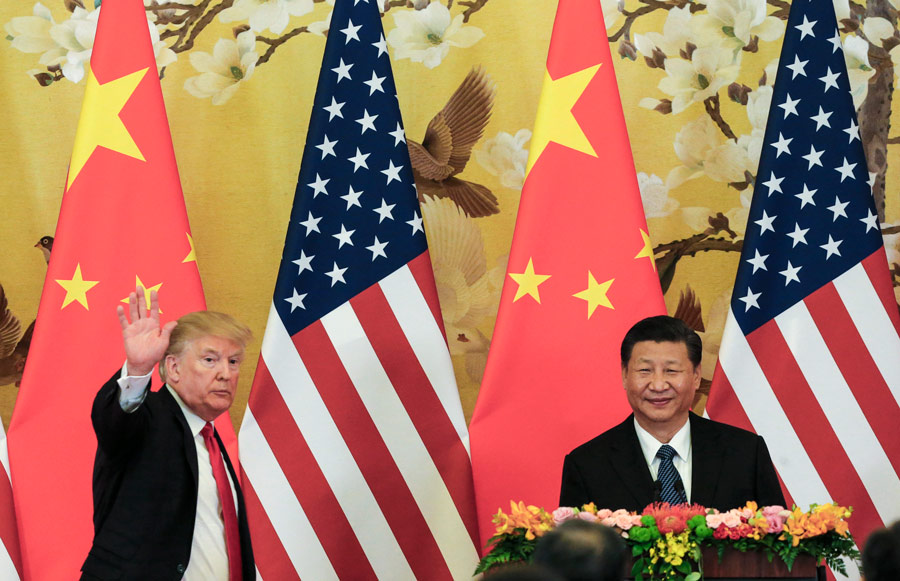

Xi signaled this early in the year at the World Economic Forum in Davos. Taking the stage on the opening morning and exuding confidence, Xi commanded his audience and his speech was beamed live on CNN around the world. Xi told the delegates that China would be an upholder of economic globalization and was prepared to play a leading role in global governance. This message was extremely well received, particularly as the world was bracing for a new U.S. president, Donald Trump, whose rhetoric indicated overt hostility to the forces of globalization and the multilateral institutions of global governance. At the very moment that the United States seemed to be stepping back from a half-century of global engagement and leadership, China was seen to be stepping up and embracing the role as new global leader. This stark juxtaposition was not lost on the delegates at the World Economic Forum nor diplomats and observers worldwide.

As 2017 played out, that is exactly what the world has witnessed. On the one hand, America has withdrawn from one global commitment after another, and has a U.S. president filled with ego, bravado, and a false sense of security, alienating allies and indulging adversaries. On the other hand, the world sees a secure Chinese leader, whose power was consolidated at the Congress, and who casts a confident posture on the world stage. His country, instead of stepping back, is stepping up and looking forward. It is moving to fill vacuums left by the United States in Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere.

A review of China’s diplomacy during 2017 reveals considerable activity. President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang each visited ten countries during the year. Xi’s travels took him to an eclectic mix of countries: the U.S., Russia, Germany, Finland, Switzerland, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, Ecuador, Chile, and Peru. In Beijing, Xi played host to no fewer than 24 visiting presidents or prime ministers plus the Secretary-General of the United Nations. The list of state visitors included two from North America, five from Latin America, two from Africa, two from the Middle East, five from Europe, and eight from Asia.

Throughout the year, China also participated in high-level dialogues with the United States, Canada, France, the United Kingdom, European Union, Russia, Indonesia, Singapore, South Korea, and the sixteen Central-East European states. All of this bilateral and multilateral diplomacy advanced China’s ties with these states and regions.

Two other key highlights for China’s diplomacy during the year were to host the Ninth BRICS Summit in Xiamen and the inaugural Belt & Road Forum in Beijing.

Xi Jinping tried to breathe new life into the BRICS with his opening speech. The BRICS have stumbled along over nearly a decade as an organization in search of a substantive mission. Some individual members also have difficult bilateral relations with each other—notably China and India, but Brazil’s relations with China, India, and Russia also reveal strains. Nonetheless, Xi’s speech echoed some of the themes he struck at Davos:

“We need to make the international order more just and equitable. We should remain committed to multilateralism and the basic norms governing international relations, and work for a new type of international relations. We need to make economic globalization open, inclusive, balanced and beneficial to all, build an open world economy, support the multilateral trading regime and oppose protectionism. We need to advance the reform of global economic governance, increase the representation and voice of emerging market and developing countries, and inject new impetus into the efforts to address the development gap between the North and South and boost global growth.”

The inaugural Belt & Road Forum held in Beijing in May was probably the highlight of the year for China’s diplomacy. The Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) is an extraordinarily ambitious set of projects to connect Asia and Europe via a vast web of transportation and other infrastructure—“connectivity” the Chinese label it—that will facilitate commerce and a range of people-to-people initiatives. It is comprised of two principal routes, one overland and one via sea: the Silk Road Economic Belt running from China across Eurasia to Europe, and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road linking China to Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean littoral, East Africa, and up to southern Europe via the Red Sea. From these two main routes, six separate arteries spin off into various countries. While still in its early stages, the gargantuan project involves sixty countries and will cost somewhere around an estimated $12-14 trillion. In May 2017, Xi Jinping gathered together sixty heads of state and other representatives in Beijing to formally launch the BRI, and his speech to the conclave laid out a wide variety of commitments and investments.

All in all, 2017 must be considered a banner year in China’s global diplomacy. We may look back on it as the year when China cemented its place as a major power in world affairs and reassured the world of its commitment to upholding the existing international system. In my view, Xi’s commitments to contributing to global governance end the long period of China’s “free riding” and reveals that Beijing is finally becoming the “responsible international stakeholder” that others have called for. This is a significant breakthrough for Beijing, and Xi Jinping deserves much personal credit for it. To be sure, China continues to have difficulties in its bilateral relations with certain countries, and its unabated rise in world affairs continues to give angst to others; Beijing will have to manage to assuage these anxieties—but, overall, we should note the major trend of China having hit its diplomatic stride. This is good for China and good for the world.

The author David Shambaugh is Gaston Sigur Professor, George Washington University.