Smaller banks vulnerable when loans sour

Big Five' lenders see NPLs on the mend amid economic growth; while those of smaller players on the rise

If the latest annual results of China's "Big Five" lenders are anything to go by, the worst may be over after a stagnated spell of being saddled with bad debt that had vastly crimped their profit margins.

The banks' 2017 performance sheets came up with some handsome figures — net interest margins on the rise, profits up and, most notably, nonperforming loans (NPLs), which have long been irking investors and denting stock prices, are on the mend.

On the other hand, some of the biggest fines have been slapped on joint-stock commercial banks for illegal lending and the size of souring loans for smaller rural banks are on the rise, raising concerns over whether the rosy loan numbers of the country's biggest lenders is evenly shared with the cash-strapped smaller lenders.

Mainland banks generally adopt the international five-category loan classification system, which grades bank loans according to their inherent risks as pass, special mention, substandard, doubtful and loss.

Pass loans are those that are in good shape; special mention loans are overdue loans, but the banks don't see them as impaired, while the other three categories are collectively referred to as NPLs that are subject to impairment of varying degrees.

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) — the country's largest lender by assets — recorded NPLs of 1.55 percent at the end of last year, down 0.6 percent from 2016, and was the biggest drop among the "Big Five". Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) also saw its NPL ratio — the highest among them — trimmed from 2.37 percent in 2016 to 1.81 percent in 2017.

Good fundamentals

Solid economic growth, higher industrial prices that pushed up companies' profits and hence an enhanced solvency that effectively embellished their loan books have vastly contributed to improved asset quality.

"With decelerating growth in 2015, producer prices were heavily negative. But, last year, producer prices were positive and interest rates were much higher," said Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief economist for Asia-Pacific at French investment bank Natixis. "Their asset quality is better, I mean, they can't be worse than in 2015."

The Producer Price Index — which measures the cost of goods at the factory gate — fell sharply in 2015, gravely stunting corporate profitability. It bottomed out from a negative 5.9 percent at the end of 2015 and peaked in 2017 with a reading of almost 8 percent before cooling off this year.

Apart from good economic fundamentals, a rebalancing of State-owned banks' loan books has also made them look healthier and less risky.

"We've seen the big lenders reducing loans for the older, saturated industries such as coal and mining, and lending more to the new economy sector," said Gary Ng, economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis in Hong Kong.

While the biggest lenders are cutting their exposure to corporate loans, there has been a notable shift to household loans in the form of mortgages and credit cards, which are considered less risky, he noted.

Mixed scene

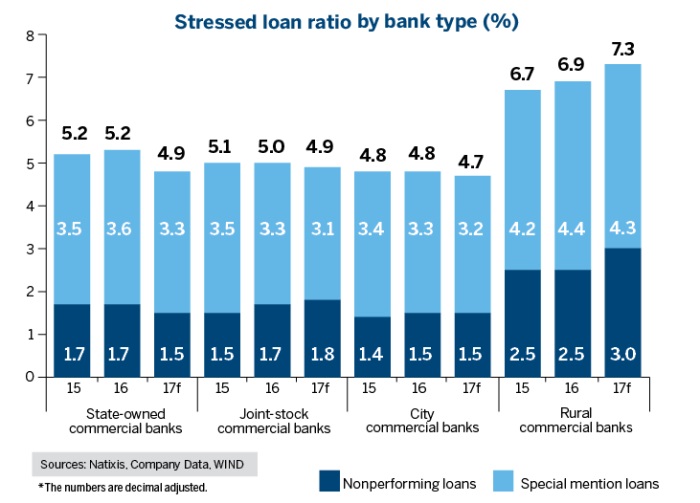

The Chinese mainland's existing commercial banking system is largely divided into four categories — five large State-owned commercial banks (SOCBs), 12 joint-stock commercial banks (JSCBs), hundreds of city commercial banks (CCBs), and thousands of rural commercial banks (RCBs).

The NPL ratios for the cash-rich SOCBs and the rest are diverged.

According to the latest Natixis China Banking Monitor, for the first half of 2017, while NPLs for SOCBs fell from 1.7 percent to 1.5 percent, JSCBs saw theirs rise 0.1 percent, and those at RCBs surged from 2.5 percent to 3 percent.

And, rising interest rates at home and abroad are hurting smaller lenders. While they enjoy a tip of surging loan rates but, with a narrower deposit base, they have to put up with heavier funding costs in the interbank market, where the State-own banks are the biggest lenders, noted Herrero.

Recent years have seen cash-strapped city and rural banks join the rush to seek listings in Hong Kong.

Less competitive rates have push second- and third-liner banks to turn to clients that are willing to pay higher rates that come with higher risks too.

Wild west

Management analyses of several listed city and rural banks show that the high cyclicality and poor risk resilience of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which constitute the majority of their corporate client base, are the primary reasons for their vulnerable and volatile NPLs.

A loans account manager with a rural bank in an eastern costal province on the mainland, using the pseudonym Liu, claimed that she had seldom encountered defaults by borrowers.

"But, for small banks like us, even with one single case of default, it would spell doom for that year," she said.

Risks could rise unexpectedly, Liu recalled that on one occasion, her bank had lent 20 million yuan to a local businessman who got addicted to gambling and subsequently defaulted, forcing the bank to turn to the guarantor to persuade the debtor to try to revive his failed business and pay up.

However, she reckoned that even in an economic downturn, a good loan business record could still be maintained with thorough due diligence, especially in places where everyone knows each other.

It's the profit-driven mentality to meet performance targets, and relatively loose internal control in smaller banks that can exacerbate the problem, she said.

In January this year, Shanghai Pudong Development Bank (SPDB) was slapped with a $72-million fine — the biggest fine so far this year — after it was found that its branch in Chengdu, Sichuan province, had extended 77.5 billion yuan in credits to 1,493 shell companies in a bid to cover up loans that had gone sour. It led to the bank posting the highest NPL ratio of 2.14 percent, among the 12 JSCBs in their 2017 annual reports.

As SPDB's branches compete with each other over profits, its Chengdu branch, which had been a star performer for years, was "favored" by the management and received less scrutiny, leaving the massive fraud undiscovered for years, an accounts manager for corporate loans at the bank told China Daily, requesting anonymity.

In Liu's view, SOCBs are not unscathed despite the loopholes. "Their books may look pretty, but they have their own way of tackling it."

Banking experts suspect that the exclusive access to some cleaning-up methods, such as debt-for-equity swaps — a scheme that let lenders become shareholders in an attempt to put troubled companies back on track through management restructuring — has also contributed to SOCBs' declining NPLs.

Due to potential conflict-of-interest concerns, original bank lenders are not encouraged to swap debt for equity directly. Instead, new entities, backed by asset management companies, insurance companies and State-owned funds, are established to pay off loans for equity swaps.

Natixis's research found that, in many cases, the original banks are big shareholders of such investors, leaving the market to question if the problem loans are solved or spinned off in a "matryoshka game".

ICBC, ABC and China Construction Bank didn't respond to China Daily's request for comments.

Contact the writer at [email protected]