In the steps of the enigmatic black dancers

But two things are beyond dispute. First, they entered the lives of the Tang people in an intimate way, attested to by the abundance of their pottery renditions in Tang-time tombs. Second, their arrival in large numbers in Tang China was made possible by the fast development of the ancient Silk Roads, including the terrestrial route and the maritime one.

The terrestrial one, the more famous one, is composed of a network of trans-Eurasian trade routes connecting the Chinese heartland with the Eurasian steppe, the Mediterranean countries and the Indian subcontinent. The maritime one linked China to Japan and the Korean Peninsula to the north and Southeast Asia and Africa to the south.

"Some of these men may have been purchased - or captured - by local tribal leaders or human traders in one of those Indian Ocean islands," Ge says. "From there they could have traveled to what today is Vietnam before moving further toward the heartland of the Chinese empire. Their existence in Tang China has cast a tantalizing beam of light on the society of their adopted home, although most details of that existence are likely to remain forever shrouded in mystery."

Ge says that the Kunlun slaves, with other non-Chinese domestic servants, were so popular at the time that having them within the household became not only fashionable but de rigueur for the rich.

"It was a fashion and a fad that reflected a general fascination with things exotic, a fascination that gripped all of society."

That was more than half a millennium after the initial opening of the terrestrial Silk Road, by a man named Zhang Qian, between 139 BC and 126 BC. Over the following centuries a great miscellany of people traveled on Zhang's road, while having it constantly extended and expanded. Frequent cultural and commercial exchanges ignited the interest of the Chinese toward the outside world, and the sparkle turned into a bonfire during the era of Tang.

The Kunlun slaves were seen less as domestic servants and more as the embodiment of a foreign land, land of which their masters could only have imagined.

And they dazzled not only with their crowns of curls. A Tang Dynasty pottery figurine unearthed in Xianyang city, a little more than 20 kilometers north of Xi'an, in present-day Shaanxi province, captures a Kunlun slave in a dance act. His torso is twisted, the palm of one hand faces down, the other hand is raised in a tight fist, and he wears a beaded necklace, bangles and rings. You get the feeling that no banquet would have been complete without a few of his dynamic moves.

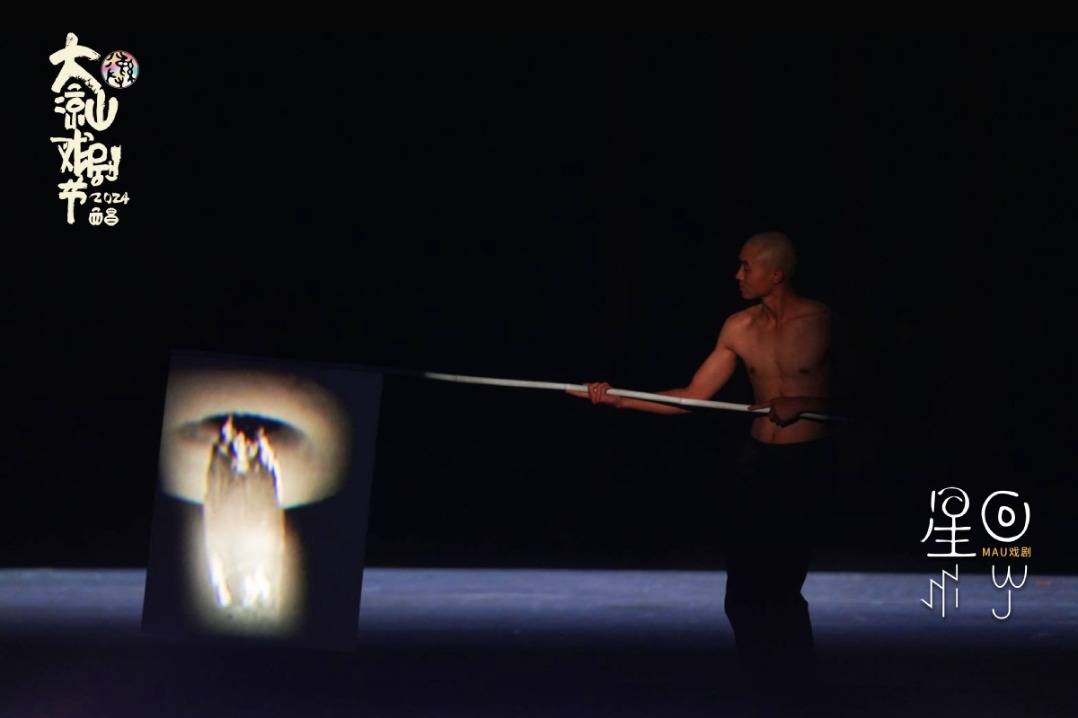

In another equally vivid rendition, a black teenage boy, half-naked, does a rod dance. Yet more moving than the dance gestures are his well-proportioned body, supple skin and a youthful elegance enhanced by palpable athleticism. Both images were on view at a previous Silk Road exhibition in Hong Kong to which Ge was a consultant.

"They could be entertainers or even acrobats," he says.