A new look at human evolution

A British historian's two-volume book tracing the development of human thought and how it has made us who we are over time has been released in Chinese. Fang Aiqing reports.

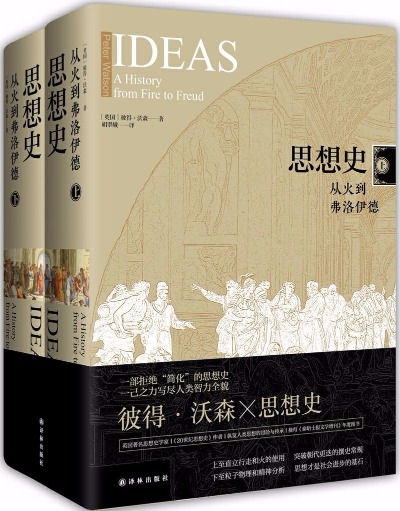

Despite the popularity of short works on history these days, British historian Peter Watson sticks with his form of comprehensive writing. And his persistence is showcased in his two-volume work of more than 1,000 pages called Ideas: A History from Fire to Freud that was recently published in China.

The work dwells on the key achievements of mankind from the time humans started walking upright and making fire to the year of 1900, when Sigmund Freud became well-known for his theory of psychoanalysis.

Watson's work, together with one of his earlier books, The Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the 20th Century, which has been translated into nearly 20 languages, provides an integrated picture of the intellectual evolution of humankind to explain how we have become what we are today.

"Reading the book is like entering a museum of human thought, but the collections and the way they are displayed are quite different from ordinary museums," says Mu Ye, a Chinese poet and editor of the magazine Shanghai Culture.

Watson, 75, is a journalist-turned-scholar who was once a research associate at the McDonald Institute for Archaeology Research at Cambridge University.

He has also published dozens of books, both nonfiction and novels, some under the pen name Mackenzie Ford.

Watson says he came up with the idea of writing about intellectual history in the late 1990s. He was inspired to do this by the British philosopher Sir Isaiah Berlin.

Watson then made up his mind to write a history of ideas of the 20th century, which was later expanded to cover a longer period of time.

Watson's work not only includes abstract ideas, but also the products of ideas that have had social consequences.

One example in his work is the invention of the guillotine during the French Revolution.

Before the revolution, there were more than 100 ways to execute prisoners. However, the invention was not only a more efficient one, but also a deliberate way of equalizing punishment.