Exporting sci-fi beyond imagination

Sci-fi grew in popularity in the late 19th century, spurred by technological advancements. Early best-sellers include H.G. Wells' The Time Machine (1895) and Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864).

Chinese science fiction began to grow in the early 20th century, says Nathaniel Isaacson, associate professor of modern Chinese literature and cultural studies at North Carolina State University.

Back then, the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was collapsing, and some parts of China fell under European control. Within this identity crisis, Chinese science-fiction books emerged to explore the country's place in the world. Isaacson names Wu Jianren's 1908 short story New Story of the Stone as an example.

New Story of the Stone imagines a world where Shanghai has become a world center of trade and commerce, and hosted a world expo and global political summits.

"Fairly often, what they imagined was a future where China is politically, economically and culturally dominant," Isaacson says.

Early Chinese science fiction's appeal was limited. What really made it big domestically and pushed the genre to the world is Liu Cixin's generation of younger writers and translators. Their modern and international perspectives, and the impact of internet publishing in the 21st century, all played key roles.

Many of China's best-known science fictions did not go for the traditional route to market, which is through book agents and established publishers. Instead, they were often published on digital bulletin boards and forums, more for feedback rather than wealth or fame.

Early drafts were posted and editing was crowdsourced. For instance, Hao's Folding Beijing was initially published on a popular bulletin board hosted by Tsinghua University.

But the internet is a place where impact can escalate quickly.

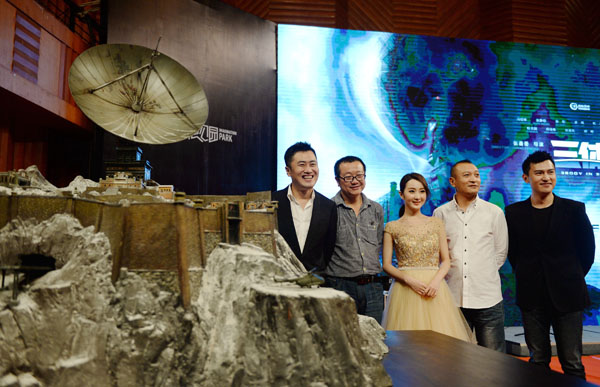

When The Three-Body Problem was published in China in 2006, internet fans loved it. They composed songs, created fake trailers for the movie they hoped for, adopted social media personalities based on Three-Body characters and wrote fan fiction.

The real international breakthrough of The Three-Body Problem trilogy came when China Educational Publications Import and Export Corp took the risk of commissioning English translations of the Three-Body trilogy.

The US publisher Tor Books bought the book's English rights from CEPIEC and made it big in the US with more than 700,000 copies sold.

House of Zeus bought the trilogy's UK and Commonwealth countries rights from Tor Books, facilitating its entry into familiar British bookshops such as Waterstones and Foyles.

Globally, it is published in 10 languages, thanks to other publishers who have bought the rights in their own markets. The sales of the French, Spanish and German versions have each exceeded 30,000 copies.

Ji of Future Affairs Administration believes Chinese science fiction's international appeal will continue, alongside China's fast-paced scientific advancement.

"The background of the golden age of science fiction in the US was its fast-developing science. So, right now in China, science and technology are developing so fast that it changes people's lives every day," Ji says.

Others, including Cheetham, want to be more careful about making generalizations about so-called Chinese science-fiction writing.

"Science fiction is a diverse scene. I would be careful to make generalizations about whether this is a Chinese trend or not," he says.

House of Zeus is launching Chen Qiufan's The Waste Tide and Bao Shu's The Redemption of Time in the UK market in 2019. Cheetham hopes these books will share some of the proven luck of previously successful Chinese science fiction.

If the author's voice matters, Liu Cixin makes it clear that although he is Chinese, he hopes his work reflects the concerns of all human beings.

"It is not my purpose to show the reality of China from a science-fiction perspective. This may not meet the expectations of Western readers. My purpose is very simple: that is, science fiction itself," he tells China Daily.