Caught in an unending twirl

"At the end of the twirl, the emperor was left in a daze," wrote the Tang Dynasty poet Yuan Zhen in the aftermath of the shock, offering mild criticism of Xuanzong, himself a music virtuoso and aficionado of the Hu dance.

The rebellion, taking more than seven years to quell, not only sapped the powerful empire of all its energy and zeal, but also represented a turning point of the fortunes of the Sogdians in China.

Overnight, infatuation was replaced by mistrust, if not hatred, and openness by rejection. Economically and emotionally, a weakened Tang Empire was no longer the market it once was for Sogdians, whose own status on the Silk Road was also challenged by Arabs from the west and by Uygurs from the east.

"It is fair to say that in terms of doing business, the Sogdians were the teachers of the Uygurs living in what is today Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in western and northwestern China," Rong says. "The two people also intermarried. By the 10th century the Sogdians had largely retreated from the center stage of international trade."

The dust they and their pack animals had aroused on the Silk Road also gradually settled: although a dramatic decline took place much later, around the 16th century, the kind of brisk trade the Sogdians witnessed was never repeated.

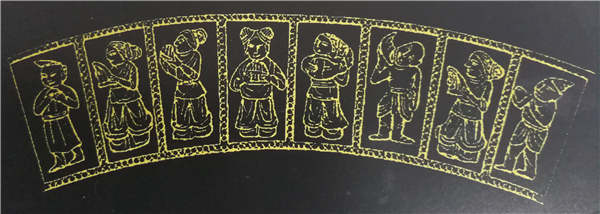

On a pair of stone gates leading to a Tang Dynasty tomb in Ningxia Hui autonomous region, northwestern China, are two dancing Sogdians. With one leg rooted on a round carpet and the other lifted up, each is engaged in a spin of their own. Everything else - the ribbons, the upturned skirt hems and even the surrounding clouds - spin with them.

For a moment it may seem they will never stop.