Economic interconnectivity of Tibet

China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective

Economic interconnectivity of Tibet

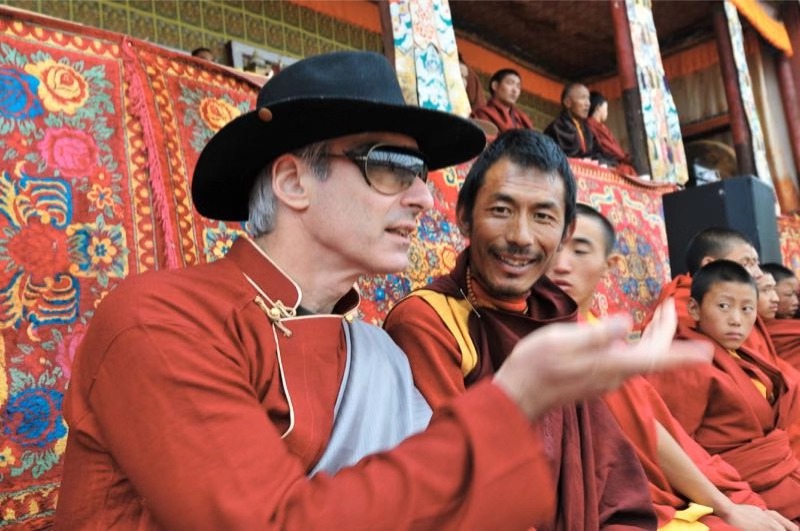

Editor's note:Laurence Brahm, first came to China as a fresh university exchange student from the US in 1981 and he has spent much of the past three and a half decades living and working in the country. He has been a lawyer, a writer, and now he is Founding Director of Himalayan Consensus and a Senior International Fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

He has captured his own story and the nation's journey in China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective. China Daily is running a series of articles every Thursday starting from May 24 that reveal the changes that have taken place in the country in the past four decades. Starting this month, China Daily will run two articles from this series each week – on Tuesday and Thursday. Keep track of the story by following us.

2007, Lhasa: I awoke each morning to the sound of local people doing their morning kora,or circumambulation, reciting mantra while turning handheld prayer wheels, as they passed along the alleyway outside my window. Each morning I would buy Tibetan flatbread from the lady who gave her profits to wandering street children.

At the alleyway crossroads of Tsongsikhangmarket, dried Tibetan cheese was piled high at stalls. The fragrance of red chili and yellow cumin overflowed from the wooden trays of spice vendors. This juncture between alleyways was an ancient traders’ market, in unbroken service since the seventh century when the city was first built. Nomads from Kham wearing chunks of amber and turquoise around their necks and red tassels tied to their hair from which coral pieces dangled, chatted into dusk excitedly trading semi-precious stones, saddles and pelts. All of this occurred daily, just minutes from the front door of my Tibetan courtyard house. I observed each day how every aspect of the kaleidoscope of color in these alleyways was actually part of an integrated economy. I realized that the success of what we wanted to achieve with our social enterprise would depend upon joining that integration.

In the afternoon Pembala and I usually walked through the neighborhood, visiting artisans in their shops, asking if they wanted to work on our products. Together Pembala and I designed everything needed for this little hotel. We sketched designs with pencil on scraps of paper and gave them to the artisans. Only traditional materials were to be used.

Soon the whole neighborhood became stakeholders in Shambhala.

When we wanted to create coffee cups, plates and bowls for our first restaurant, Pembala and I traced the source of Tibetan ceramics. We did this by talking with migrant street vendors squatting in the alleyways selling earthenware. The source led to a village about three hours from Lhasa. Here the earth was a deep red. The pottery village specialized in ceramic vats to store chang. However, production was in decline because Chinese-manufactured plastic and aluminum products were cheaper. With no money in pottery, young people were leaving to find work in cities. Pembala and I suggested modifying the natural shape of traditional ceramic vats and storage bowls to create cups, plates, and vases for shampoo and bath lotion. With three hotels and three restaurants in the planning works, we kept the villagers quite busy revitalizing their craft. The best thing about the plates and coffee cups they made for us was that no two matched at all. It was all just pure art.

We decorated the restaurant tearoom with antique door panels collected from western Tibet during the filming of Shambhala Sutra. When it turned out that guests were keen to purchase and collect them, we made reproductions small enough to pack in a suitcase. Before we knew it, the entire neighborhood was making them.

We had sparked an artisan revival without even knowing it.

People in the neighborhood were thrilled to see one of their old buildings being restored so painstakingly. It amused those that soon discovered a foreigner was behind it. Sometime they sang lyrics from a popular song. "Shambhala is not far away" adding with laughter "Shambhala is my next door neighbor".

Tibetans live by a natural rhythm. There was no separation in their minds between the spiritual and material worlds. Their thought process is intrinsic. Time is somewhat irrelevant. For instance, the word guongda "afternoon" really means anything from lunchtime onwards, including all night. Things flowed without specific context or deadlines. By living in the old city interacting with Tibetans each day, I was making a conscious effort to step out of our western pre-conceived rational thinking box.

Walking through these busy alleyways, I often stopped to chat with a monk who sold yak butter in a little shop. He always cut a tiny sample with a broad knife, offering it as I walked by. Yak butter is essential for Tibetans. Mixing it with black tea, they drink it all day long, and it provides calories and vitamins they need to survive at this high altitude. Throughout the day every Tibetan household burns yak butter as offertory candles adorning home shrines. Of course it is used in cooking. I found that yak butter proved the best protection against sharp ultra-violet rays of the highland sun. Every morning I rubbed it on my face and arms.

The yak butter sellers in my neighborhood came mostly from Amdo, or Eastern Tibet, which is a nomadic region. I remembered what the monk Jigme Jensen had taught about the importance of letting nomads continue to live as nomads. Yak-grazing patterns have been on the highlands since people crossed the Bering Straights. Yak migration is an integrated part in the delicate bio-diversity of the Tibetan plateau.

I began to think about the economic interconnection of all things. Whatever was happening in our neighborhood was intimately connected with the sustainability of the Tibetan plateau, and in turn global climate change. All things were interconnected, in ways that often were not apparent, but always present.

By restoring traditional homes as small family businesses, shops, teahouses or guest lodges, people would not have to move out, as developers wanted, and some government officials insisted. The neighborhood could have an economic platform that would evolve and sustain culture rather than change or break it. People would continue to live in the old neighborhood, buy yak butter for their tea and family shrines. The nomads in Amdo could continue herding yak. And the patterns of grazing that had kept balance in the grasslands for millennia could remain.

Please click here to read previous articles.