Virtual shopping is favorable but there are downsides to the retail revolution

A traditional approach to history has been to focus on the significance of factors such as war, conquest and dynastic competition in determining world affairs. Modern historians, however, tend to focus on the influence of a much more pervasive if more mundane factor - shopping.

What and how we buy, sell or barter has probably had more effect on human progress than the triumph of armies or the rise and fall of empires. Contacts between previously isolated civilizations have invariably been spurred by a desire to gain access to the rare goods that each had to offer.

That is how Chinese silks and spices made their way to northern Europe while furs from the frozen north ended up being traded in the markets of the East.

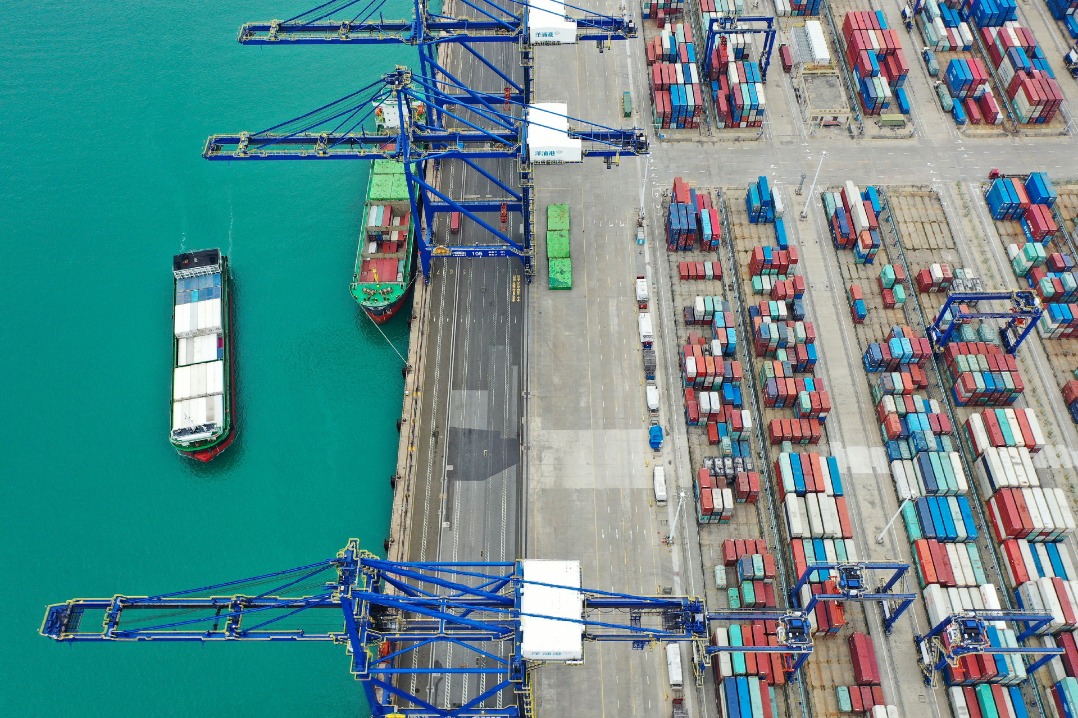

These exchanges have grown more sophisticated and complex across the millennia, leading to the present era of globalized trade. But, in essence, initiatives such as Belt and Road Initiative are an extension of a long-established pattern of making goods produced in one part of the world available in another.

The way these goods make their way to the final consumer has also remained broadly unchanged across the centuries: they end up in the physical world of markets and shops.

Like so much else in the connected 21st century, that tradition of interchange may now be headed for the historical dustbin. Consumers increasingly opt to buy online via their laptops or mobile phones rather than heading for the market or the mall.

Online giants such as Amazon, JD and Alibaba have come to eclipse traditional retailers, many of which have gone to the wall in what analysts have described as a retail Apocalypse.

In the United Kingdom, once thought of as "a nation of shopkeepers", the sector shed 70,000 jobs in the final months of 2018 amid a series of retail bankruptcies.

Elsewhere in the developed economies, where a migration of retail to out-of-town malls had already devastated traditional city center shops, the malls themselves are now under threat from online competitors.

It might be argued that a switch to virtual shopping can only be beneficial: it puts more goods at the disposal of more people than physical retail was ever able to do. Shoppers can save precious time they previously expended on trekking from home to market and back again. The use of delivery drones will even help to reduce on energy use.

But there is also a significant downside. From ancient times trade contacts were about more than just goods. Trading posts and caravanserais,or roadside inns, along the ancient Silk Roads were also a focus for the exchange of ideas, traditions, culture and art.

At a local level until modern times, shops and markets have also provided a meeting place for social exchanges, a chance to meet other people and swap news or gossip.

In those countries of Europe where the retail revolution has driven small shops out of city centers, locals complain that the soul has been ripped out of their communities.

At the same time, the mega-malls that have sprung up in both the developed and developing economies have come to provide some of the social interchange once provided by old traditional markets.

In the long run, online retail threatens even these modern meetings places. It is not hard to imagine a dystopian world in which we all stay at home and our only social interchange will be with the online robot that is taking our order.

In the face of these challenges, there is what might be thought of as a retail fightback. Innovative retailers have built on the attraction of the physical market place to adapt their businesses.

Booksellers, who just a decade ago faced the prospect of being wiped out by e-books, have successfully fought back by incorporating cafes, meeting spots and cultural spaces.

Big store chains have adapted to the new market by realizing that physical shops are now basically a showplace for the goods they have to offer. Shoppers will go there to see physical products and then go home to make their final purchases online.

Perhaps the final proof that physical shops and markets still have a future is the fact that online giants have decided to open shops of their own.

In the United States, Amazon and a range of smaller online companies have invested in bricks-and-mortar outlets to provide greater exposure and boost their sales.

And in China, which became the largest e-commerce market in the world in 2013, the same phenomenon is apparent.

A survey by consultants PwC found that 86 percent of Chinese respondents, compared to an average 68 percent around the world, said they had gone to a physical store to check a product before buying online, with many citing lower prices as the reason for an e-purchase.

Online retailers may now call the shots but it might be too early to predict the death of the shop.