More than just a picture

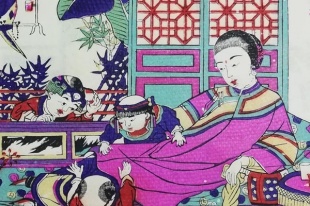

One artwork at an ongoing exhibition at the Shanghai History Museum portrays a parade led by a trumpeter, who is followed by a bride in a sedan chair, her family members and guests, some of whom are carrying gifts on their shoulders.

It's a scene typical of a Chinese wedding in the past. But what makes this Lunar New Year print truly unique is that mice are in the frame, not humans.

A popular folk tale in many parts of China, the wedding of the mice has different versions, but the wedding parade has always been a favorite subject for folk art across the country.

"We will soon step into the Year of the Rat according to the Chinese zodiac, and we hope this vivid picture can bring some joy to our visitors and arouse their interest in Chinese culture," says Zhang Rongxiang, head of the Chongqing China Three Gorges Museum.

The exhibition at the Shanghai History Museum showcases 87 artworks from its collection and that of the Chongqing China Three Gorges Museum. Most of these artworks were created during the period spanning the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) to the early 20th century.

Chinese have been putting up pictures of renowned marshals and generals on their gates since as early as the Han Dynasty (202 BC-220), hoping that the valiance and reputation of these figures would prevent evil spirits from entering the home. This practice, which is part of Chinese New Year celebrations, then became common with the advent of print technology during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127).

Lunar New Year prints, or nianhua in Chinese, have since become a unique genre of folk art that is deeply rooted in the lives and beliefs of ordinary Chinese, says Hu Jiang, director of the Shanghai History Museum.

"These pictures reflect people's wish for a good life, their life philosophy and beliefs. It also shows the wit, wisdom and entertainment of ordinary people," he says.