Rebalancing the old and new economies

Around 2000, I attended a business debate in Mumbai, India, whose content, it seems in retrospect, is proving to be prescient in the context of the current novel coronavirus developments.

Two stalwarts of Indian industry were invited to debate the "Old Economy versus New Economy" theme.

A little background: Back then, India was shaking off decades of economic and policy drift by seeking to consolidate early gains made in the emerging IT industry. Big investments in software gave the country a head start over other emerging economies.

IT and software education firms not only mushroomed but were listing on the bourses. Equity investors, venture capitalists, media, lenders, bureaucrats, politicians, career-minded youth ... everyone came under the IT spell. Pundits argued that India's future lay in services, not the old economy of agriculture and low-quality manufacturing.

IT, tourism, hospitality, banking and financial services, online content, dot-coms and so forth-all glamor, and limelight-hogging-were referred to as the new economy. In the 1950s, agriculture accounted for 53 percent of the Indian economy, with industry taking 20 percent and services 27 percent. By 2000, the three sectors' shares changed to 24 percent, 27 percent and 49 percent, respectively, sparking intense debate.

At the Mumbai forum, Rahul Bajaj, the outspoken champion of the old economy, an industry doyen and then chairman of the family-inherited Bajaj Auto, the world's largest maker of two-wheelers then, crossed swords with Nandan Nilekeni, then celebrated chief operating officer of Infosys Technologies, India's best-known, Nasdaq-listed IT unicorn startup.

Bajaj and Nilekeni had a go at each other in a cordial, spirited way, enthralling the audience. For a while, it seemed as if Bajaj was old-fashioned in thought, in denial, bitter that the spotlight should shine on the IT Johnnies-come-lately at all. In Bajaj's view, the hoopla over the new economy's potential was a passing phenomenon, a fad at best.

Manufacturing, he said, has to be the backbone of any economy like India's. You can't wish away the old economy or play up the new economy unduly, given the 1 billion and growing population. The old economy, Bajaj averred, will prove itself to be a prerequisite.

And any unreasonable imbalances in primary, secondary and tertiary sectors, he warned for good measure, would be tantamount to creating a recipe for potential disaster during trying times.

Bajaj could have been speaking not only about India but emerging economies with large populations. China's current population of 1.4 billion exceeds India's 1.36 billion (although India is forecast to be the world's most populous nation in a few years).

In the aftermath of the novel coronavirus outbreak, policymakers and economists worldwide will likely find themselves revisiting and reviewing afresh the "old economy vs new economy" debate, if not urgently recommending a rebalancing of the sectoral proportion of big economies with large populations.

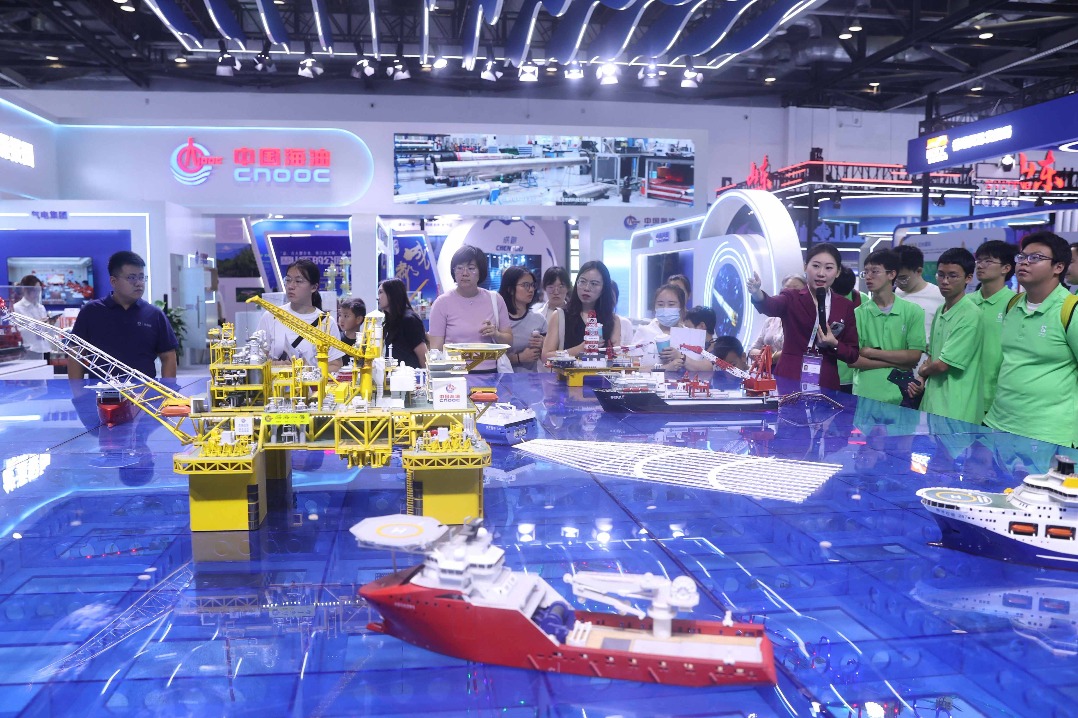

According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, China's GDP in 2019 was 99.09 trillion yuan ($14.1 trillion). Agriculture now accounts for some 7 percent of the economy while employing 26 percent of the total workforce; industry contributes about 39 percent to GDP while employing 27 percent; and services generate around 54 percent of GDP and provide 47 percent of jobs.

In 2019, services accounted for the largest chunk-47 percent-of financial institutions' outstanding medium-and long-term loans; they also received more than 72 percent of the $137 billion worth of foreign direct investment in China.

This has been the broad trend for a while now, and is largely true of even investments in the local as well as global startup ecosystems. This may appear progressive, even visionary, in the normal course of events. But, both history-wars, scandals, recessions, depressions, natural disasters, pandemics, new technologies and geopolitical factors-and the novel coronavirus have shown potential game-changers are only to be expected.

Factor in the hyper-globalization of the last two to three decades and you have a planet entangled in heavily interconnected systems or mechanisms, interdependent markets and intertwined economies, where not a single community, sector or business segment is geographically self-reliant. And the quality of healthcare and education available in up to 80 percent of areas globally hardly correlates with 21st-century possibilities.

"Breaking news" of a royal pregnancy can brighten mood in one country, and spark off a global chain reaction almost instantly: a potential boom in mom and baby products (as more women may decide to have babies); a surge in stocks of companies making such products; glad tidings for suppliers to product-makers; rising demand for this commodity or that service; buoyancy in a slew of currencies; changes in global oil prices; knock-on effects on several industries.

The flip side of that is, a black-swan event can also floor farming, maul manufacturing, savage services, and bring the globalized, heavily digitalized and economy-first world to its knees, all in a matter of weeks.

Celebrated former IMF chief economist and former Indian central bank governor Raghuram Rajan, who famously predicted the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (and was promptly snubbed by the high priests of US economic policy), has cautioned against excessive use of monetary and fiscal tools in the global epidemic combat. Instead, conventional epidemic controls-science, medical-care, order and logistics-should receive top priority.

That's easier said than done. That is because populous emerging economies are addicted to the services sector whose temptations like quick, large-scale employment and sustained robust growth are irresistible. But coronavirus has shown it may be time to weigh such enthusiasm against potential socioeconomic pressures that may arise when an economic downturn is exacerbated by a global upheaval.

On the one hand, any massive job losses, stagnant wages, shuttering of SMEs and even en masse elimination of certain business segments could threaten a downward spiral. On the other, questions could arise on the dependence on imports of all sorts-food, energy, medicine, medical supplies, expertise and what have you. Climate activists and scientists are now linking non-vegetarianism to global warming.

When the going is good, the benefits of cities, or urbanization, appear unquestionable. At other times, however, one city could prove a concentrate of invisible trouble capable of tearing asunder the delicate fabric of interwoven markets worldwide.

The novel coronavirus has also highlighted the unrecognized dangers of a certain lifestyle shaped by market forces, as exemplified by the travails on some cruise ships. Is it then time for humanity to return to age-old questions like GDP vs GNH (gross national happiness), our relationship with nature and the planet, and the purpose of life in human form?

An aside: For all its recent thrust on services, India's IT industry is still stuck in low-value outsourced coding, an edge now being blunted by some cost-effective South Asian and ASEAN countries. Assorted Indian startups across fintech, edutech, health-tech, hospitality and e-commerce segments have proved to be more sexy media stories than real-economy achievements.

The fast-emerging consensus among experts is that the Indian economy is in a shambles and likely to miss the 2024 goal of $5 trillion GDP, even as services accounted for a whopping 61 percent of the $2.9 trillion GDP in 2019(up from 27 percent in 1950 and 33 percent in 1970).

The rise of the far right, trade conflicts, intellectual property battles, geopolitical tensions, economic inequalities and the climate change crisis should concern the world. At the same time, the novel coronavirus, it seems, is underlining not only balance in economic sectors but a certain degree of economic self-sufficiency at the local or community level, for immunity from the perils of unrefined globalization.

The author is a senior staff commentator of China Daily.