Food waste is a shameful chronic disease

When I was a young boy in Shanghai in the early 1970s, my father occasionally teased me at the dinner table:"Your grain ration is 18 jin (9 kilograms), so you can only have one bowl of steamed rice per meal." He knew I often ate more than a bowlful of rice.

Those were times of food scarcity when everything from rice and meat to tofu and cooking oil was rationed.

Food rationing has become a memory of the past. Abundant supply has been the norm for at least the past three decades, so the younger generation in China may not have any memories of food scarcity. And I don't think I could eat 9 kg of rice a month now because there are so many other foods available.

Instead, overeating and wasting has become a serious concern with expanding waistlines in China. More than 300 million Chinese are overweight or obese.

And food waste has become a chronic disease for the country, especially so when people dine out. According to a study by the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chinese restaurants wasted 17-18 million tons of food a year from 2013 to 2015, food that could feed 30-50 million people a year.

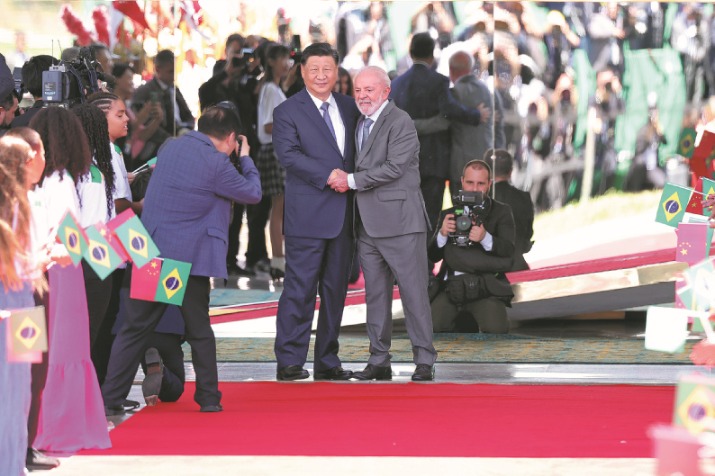

That's why the latest call by President Xi Jinping to curb food waste and food loss is important to ensure people abandon this bad habit. The COVID-19 pandemic, floods and other natural disasters that have hit China have added urgency to this campaign.

However, some Western media outlets have given a spin to the issue. They have churned out numerous headlines on China's "food shortage crisis" by citing this week's 2020 Rural Development Report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, which says China is expected to have a food supply gap of 130 million tons by the end of 2025.

Li Guoxiang, a researcher in agriculture at the CASS, has dismissed the alarmist views, arguing that China's food supply is absolutely secure. He said China became self-sufficient in food long ago, producing about 700 million tons of food at home and importing about 130 million tons from around the world. China's self-sufficiency in three major food grains-rice, wheat and corn-remains as high as 98 percent.

The so-called food supply gap is nothing new-it has remained stable, between 100 million and 150 million tons, including 80-90 million tons of soybeans and tens of millions of tons of grains, for years.

China, like most other countries, is helping the global market by importing food from economies such as the United States, Canada, Australia, Ukraine, Argentina, the European Union and Southeast Asian countries. Such imports have become a big source of revenue for the exporting countries.

While some countries have imposed restrictions on food exports since early this year due to the pandemic, the impact on China has been quite limited, according to Qiu Hongping, a researcher at the risk-info.com.

While posted in the US, I stayed with a wheat and soybean farmer's family in Minnesota, and interviewed farmers in Iowa and Montana. All of them pinned high hopes on the Chinese market. That must also be the case for farmers in many other countries. And it's unlikely that all of them will cut food exports at the same time.

For most Chinese people, food shortage is a painful experience of the past. But rampant food waste at Chinese dinner tables remains painful, and shameful, given that many people in China and other parts of the world, including in the US and Europe, are still struggling to put food on the table.

The author is chief of China Daily EU Bureau based in Brussels.

[email protected]