Positive prognosis for hospitals

Lipson talks with a child at a United Family Healthcare hospital in China. CHINA DAILY

US director of healthcare company is confident dramatic improvements will continue

The idea of setting up a network of hospitals and clinics in China offering obstetrics care came to Roberta Lipson after seeing women sharing a room during childbirth.

Lipson, from the United States, witnessed the scene when she accompanied a pregnant Chinese friend to a Beijing hospital in the late 1980s, a time when the country was undergoing a baby boom.

"I was surprised, but it wasn't because the hospitals only wanted to treat the patient in such a mechanical way," said Lipson, who first arrived in Beijing in 1979 as a marketing manager for a trading company.

"Instead, it was because the extremely busy ward and the lack of resources didn't allow them to be compassionate about childbirth."

In the 1990s, Lipson returned to the US to have her three children. She eventually relocated to China and founded United Family Healthcare, which opened its first hospital in Beijing in 1997 and its first in Shanghai in 2004.

Healthcare in China today is vastly different from what Lipson encountered more than three decades ago.

Women in cities now have access to an independent delivery room where family members, especially fathers, can be on hand to offer their support during the birth.

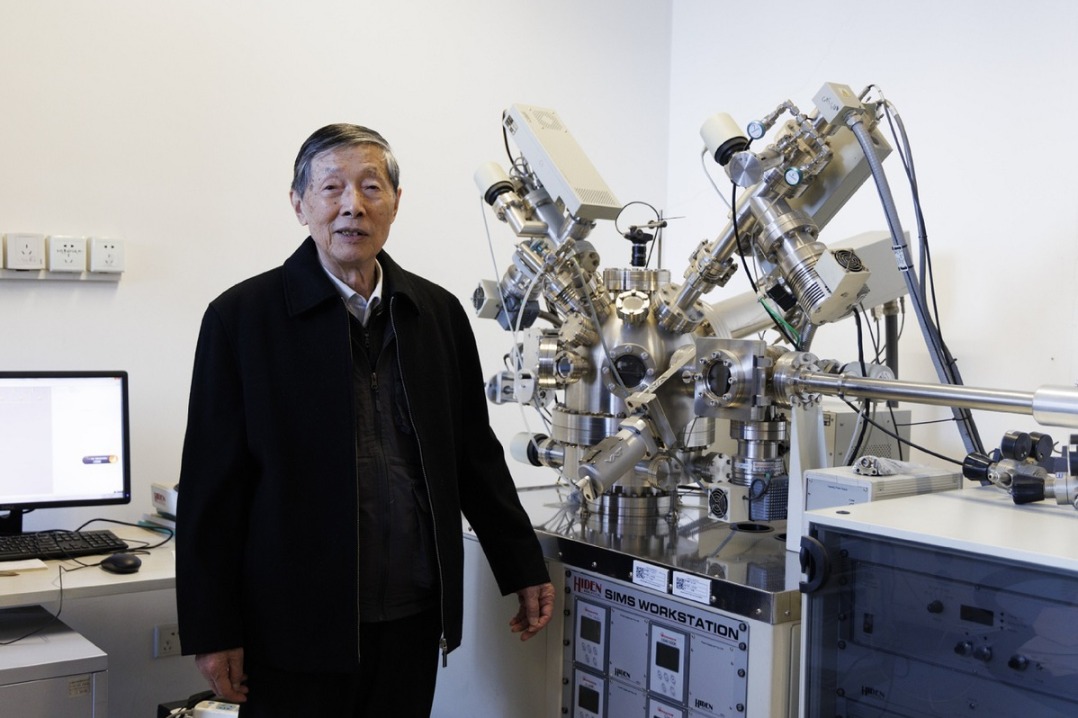

Roberta Lipson is the founder of United Family Healthcare. CHINA DAILY

"Childbirth today is not only about being as safe as possible. It can also be a pleasant experience to be celebrated as there is nothing happier than welcoming a new life," she said.

The improved conditions for the delivery of children epitomize how well-rounded healthcare in China has become, said Lipson.

She said the improvements she has witnessed in China's healthcare system over the past four decades have been incredible.

Lipson said the long-term achievements in the years following the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949 are reflected in healthcare statistics.

The life expectancy for Chinese reached 77 in 2018, more than double the figure seven decades ago. Over the same period, the maternal mortality rate decreased from 1,500 per 100,000 women to around 18 per 100,000.

The enormous strides in obstetrics can largely be put down to the nationwide management system of pregnancies, even in the countryside, better nutrition, and postnatal health checkups for babies and mothers. "Chinese women now get five free prenatal checkups for every pregnancy," Lipson said.

"For women undergoing a high-risk pregnancy, they are sent to hospitals that can really handle those risks, even in very poor rural places. I saw on the wall of one local health center a chart about all the high-risk pregnancies in the area."

Pain reduction during delivery has also made noticeable progress, she said, adding that it is important to be aware of the safety of both the mother and baby. When the mother is in pain, hormones are released, which in turn reduces the amount of oxygen to the baby, she said.

UFH was the first medical institution on the Chinese mainland to offer pain control in the late 1990s. Lipson said this increased women's awareness about reducing pain that triggered changes in public hospitals.

At least 20 hospitals in Beijing now offer pain control services for pregnant women.

"That's an example of when we serve a small proportion of people in China it brings in new approaches and has an impact on the attitudes of doctors and patients in public hospitals," she said.

The change of focus from disease treatment to prevention has been another huge improvement in China's healthcare system, Lipson said.

"From the country's perspective, it's a lot less expensive to prevent diseases than trying to cure them. Preventing diseases also stops some people becoming trapped in deep poverty," she said.

Lipson cited the human papilloma virus as an example of preventive healthcare having a positive outcome.

Repeated HPV infections can lead to cervical cancer. Before China started a free HPV screening program for rural women in 2009, the country accounted for 28 percent of cases worldwide and 90 percent of the deaths, which mainly occurred in rural areas.

In 2016, the UFH's charitable arm, the United Foundation for China's Health, began a cervical cancer screening program, which involves a team of around 20 doctors visiting poor areas of China.

The team has traveled to disadvantaged regions in Yunnan and Gansu provinces and the Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Hui autonomous regions and screened and treated tens of thousands of women, Lipson said.

"I remember meeting a woman in Inner Mongolia who said it was the first time she had taken such a screening. She said she wanted to pass the hygiene and healthcare knowledge from our team on to her daughter, who is the mother of two daughters," she said.

- A gateway to travel in China

- Researchers identify T cells causing chronic sinus inflammation

- Former head of China Geological Survey pleads guilty to bribery, leaking secrets

- Scientists synthesize single-crystal sp2 carbon-linked covalent organic frameworks

- Shanghai Museum holds snake-themed exhibition to celebrate Chinese New Year

- Pediatric rescue alliance launched in Guangdong