Doors of healing opened for a traumatized New York

What it took to reopen The Met museum in its 150th year, amid a pandemic

Gaiety and glee, galvanizing excitement bordering on exhilaration, a moment of rapture and blissfulness — a picture posted by New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art on Instagram upon its reopening at the end of August says it all through one single image. It is of a visitor, torso dramatically leaning back as if he had "stepped on a banana peel" as one Instagram user jokingly commented, with arms extended wide, ready to re-embrace a much-missed part of his life.

Years on if one were to look at the picture, the element of "when" would be just as unmistakable as that of "where", thanks to the masks worn by the man and those filing in after him.

Since then, the image has been retweeted many times and has solicited more than a couple hundred comments. "How's the flowers?" one asked, referring to the giant blossoms placed on the information desk right in the center of the great hall that greeted the overjoyed man the minute he passed the door.

Will Sullivan was the man behind that door.

"Since we didn't have the setup ready to keep the door open, I personally held the door for him, who I believe is our very first visitor when the museum opened for our members on August 27th, two days before it did so for the general public," said Sullivan, the museum's head of visitor experience.

Later that day, when Sullivan "was finally able to step away", he had "a moment of being choked up, I was standing outside the museum's main entrance and looking up and down the Fifth Avenue. I could see people waiting to come in," he said. "It was emotional because you had done everything to get prepared, but you never really knew if people were going to turn up.

"They did."

Sarah Cowan, a fellow New Yorker who, by her own admission has "grown up in the Met first by coming to the Met and then by working here for 10 years", shares that sentiment.

At the beginning of this year, while the museum was gearing up for the much-anticipated celebration of its 150th anniversary, with an exhibition proudly titled Making the Met (1870-2020), all Cowan could think about as an editor and producer in the Met's Digital Department was the making of Met Stories – a 12-episode video series focusing on visitor experiences.

Thought up as a commemorative project, it's also meant to be a personal tribute. Through her creative eye, Cowan saw such artistic shots in which "the color of the visitor's jacket rhymes with that of a painting".

She was also hoping to capture — with close-up shots — many spontaneous and intimate moments played out on the gallery floor. That was before COVID-19 and its casualties started to dominate the news, and the museum closed its doors on March 13.

Upon the museum's reopening, Cowan released her seventh episode, the only one shot "not with Steadicams and cinema lenses but using Zoom and smartphones". All footage of the empty Met, which adds an additional resonance to the stories being told in that episode, was collected by the Met's essential staff, who filmed with their mobile phones during shifts.

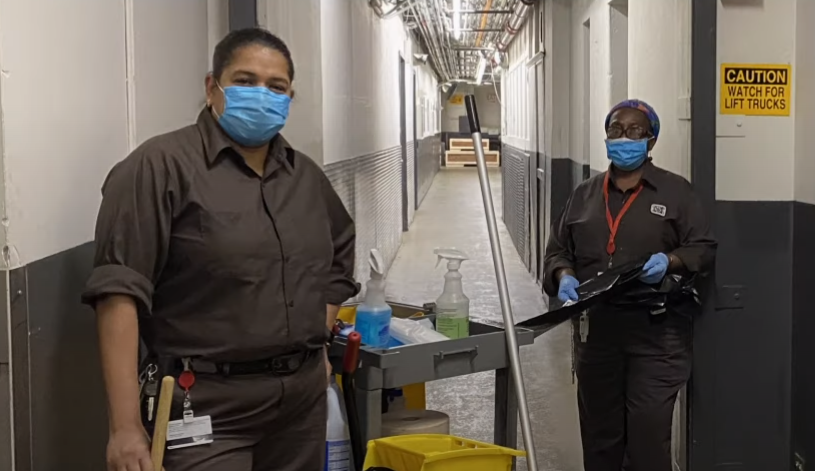

"Collection monitors, security workers, custodial workers — they all chipped in to help," said Cowan. Fittingly entitled Essential, the episode features three interviewees – an author who had made visiting the Met every day her 2020 New Year's resolution; an artist who has published two books of figure-drawing out of her intense people-watching inside the galleries; and Angela Reynolds, the Met's assistant building manager for maintenance who heads the custodial team, whose members also were in charge of cleaning the building "the way they would have done in a hospital".

"You name it, they'll write every single thing down and clean every touchable surface. It was just putting them on the front line, knowing that they were protecting themselves with all the training and PPE," Reynolds said. "In the beginning after the museum's closure, this was done on a voluntary basis, which was quite powerful."

On an average day during the Met's five-month closure, 13 to 15 people from the custodial team would work the vacant museum, where, "walking with spray bottles and clean rags", they felt their own presence through "the echoes of the custodial carts rolling down the empty hallways", Reynolds said.

They also were taking care of things that on a normal basis wouldn't fall under their responsibility, to feed the koi fish in the museum's second-floor Chinese garden court being one example.

The well-being of the fish holds particular importance to Daniel Bergmann, an undergraduate at Harvard University who is autistic. During his childhood, Bergmann was frequently taken by his artist mother to the Met, where his discovered his ultimate attraction — the 17th century-style Astor Chinese garden court embedded in the heart of the museum's China galleries. There, contemplating the koi pond and the miniature waterfall for hours on end, the boy, who was unable to speak, had an epiphany.

"I didn't even know that the sounds and sights went together and represented the same event. I thought the world offered both things I could hear and things I could see as separate phenomena," said Bergmann. Appearing in one episode of Met Stories with his parents, Bergman sits on a wooden bench in the garden and types on an iPad to express his thoughts.

"One day when I was about 9 years old, while I was looking, I suddenly realized that that the sound of the waterfall was the same event as the sight of the water falling. Sound and sight went together, and there were only half as many things to understand in the world."

Another person who has gained insight into the world and himself and had done so in a more conscious way is Michael Zacchea. He joined the US Marine Corps at 17 and was deployed to Iraq in 2004, where he was seriously wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade during the second battle of Fallujah.

"When I came back to New York City, sometimes I couldn't tell if I was in Iraq or in the United States. That's post-traumatic stress. I was really messed up," said Zacchea who, with a major in classical civilization from his college years, later started paying visits to the Met's Greek and Roman galleries.

"The American narrative of war is that it's a just war, a righteous way, and everybody goes home and lives happily ever after, and that's not the truth," he said. "There is a truth about the human experiences of war and war trauma. I could come here and see, mirrored in the broken statues, my own body," continued the veteran, who described the whole experience as a catharsis that had helped build him spiritually.

Cowan, who filmed Bergmann and Zacchea in the galleries before the Met's closure in March, called the stories "timeless and timely" for a people deeply bruised by the ongoing pandemic, an outbreak that has claimed nearly 24,000 lives in New York City and more than 200,000 nationwide.

"These works are really about individuals confronting their suffering and mortality. In that sense, they resonate with how a lot of people are feeling right now," she said. "If you just look at the comments on Instagram and YouTube, it's clear that people are looking for truthful, genuine emotional connections right now. And these stories have turned out to be extremely important touchstones."

On the other hand, even an empty Met has a healing effect, said Reynolds. On her way to work last November, Reynolds accidentally had her foot catch the top part of the stairs inside a train station, and she fell. "I hit the steel and I heard my skull crunch. It was a moment of nothingness," she said.

Although she was back to work two months later, the physical and mental impact of her brain injury has proven to be long-lasting. "I couldn't be in crowds; I couldn't go into the galleries or the great hall," said Reynolds, who found a much-needed respite when the museum closed its doors.

"This worked a little different for me than it did for others: The empty spaces gave me a chance to connect with myself, to be familiar with the museum again, and to get ready for the return of the crowds," she said.

Coming to work regularly during the entire closure time, Reynolds, who calls herself "a pre-spiritual person", would spend time in the Asian and African galleries, where she felt "strengthened".

"At this moment, we are affected one way or the other. Whether or not we're directly affected, we feel it energetically," said Reynolds. She was referring both to the pandemic and the series of tragic events involving police brutality and black Americans, who, according to Reynolds, herself an African American, "have not been given a real opportunity to heal, especially in this country".

"About 92 percent of my staff on the custodial team are black. I think they show up and they do what they need to do. But there's an awareness in them that you're going to judge them," she said. "They feel second-class because of the position they hold and the color of their skin."

Likening their role to that of "piano tweakers" as opposed to "players", Reynolds hopes that the Met video could help bring "compassion and understanding" to these invisible heroes.

But with the museum projecting a $150 million loss in revenue from the pandemic, some of her custodial staff members have been furloughed for six months starting from September.

The same thing has happened to others on the Met's security team, whose mostly black members once populated the museum's seemingly endless numbers of galleries. (The Met paid all of its employees from March 13 to the end of August.)

Last Monday, for the first time since March, Cowan was back filming at the Met. Describing the galleries as "much quieter and more contemplative", she said that it was "uplifting to see the giddiness of one of our subjects when he came upon paintings by one of his favorite artists".

While admitting that worries about a potential resurgence in novel coronavirus infections are "in the back of everyone's mind", Sullivan called the reopening "a step towards collective healing".

"For so many years, we've been welcoming people from around the world, people who don't necessarily speak English. As a result, we are used to doing that with our eyes and body gestures," he said, referring to the Met's compulsory face-covering wearing for all over age 2.

Other precautionary measures include maintaining 6 feet of social distance, reservations or timed tickets, temperature checks at the entrance and reduced visitor numbers (25 percent of regular capacity).

"In the past weeks, I have found in the galleries nothing but people being respectful of one another and of the rules," he said.

One morning when he and his colleagues were preparing for the reopening, Sullivan noticed that a van had pulled up in front of the museum.

"A bunch of people walked through the front door carrying boxes. Before I realized it, they had pulled out bouquets of flowers and started putting them in the giant vases in the great hall, kept quiet for so long a time," recalled Sullivan.

"It was a miraculous moment, a moment when the museum sprung back to life."