Future up in the air for kite collector

ISTANBUL-Egyptian student Ibrahim, who recently moved to Istanbul to study medicine, entered the kite museum out of sheer curiosity and apparent excitement.

Turkey's single kite museum in the Uskudar district on the Asian side of Istanbul has been trying to stay afloat amid the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

"I wouldn't think that I would find a museum in the city dedicated to kites," Ibrahim says, while gazing at the colorful, differently shaped kites in admiration.

Mehmet Naci Akoz, president of the Istanbul Kite Association and founder of the museum, says that he created the 3,000-piece collection over the course of 40 years and opened this museum in 2005.

He visited over 35 countries to gather kites to be displayed in the museum.

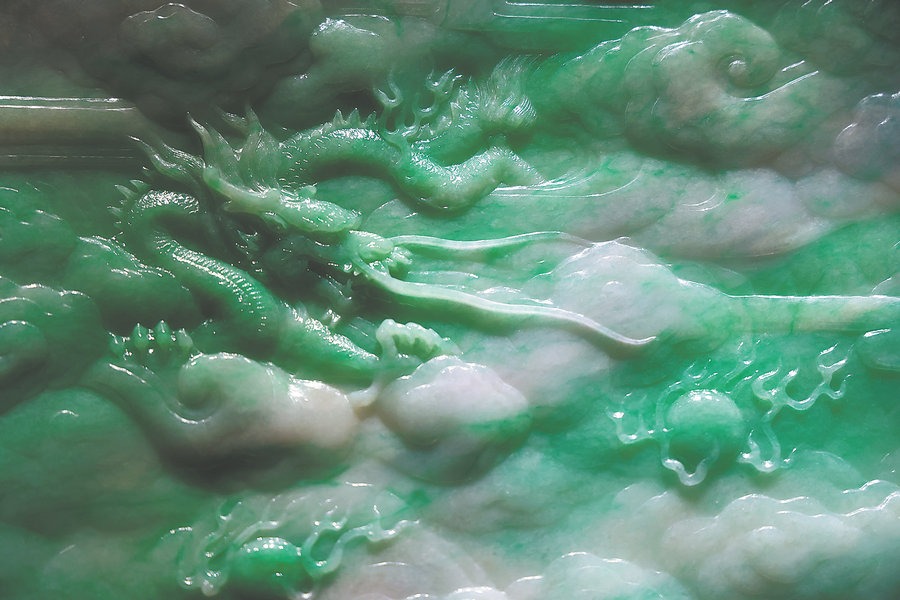

"I was most impressed by the ancient kite culture of China, dating back to 300 BC," Akoz explains, standing in front of several picturesque three-dimensional Chinese kites.

He went to China several times to collect exhibits for the gallery.

"Chinese people created kites in the shape of everything that comes to mind," Akoz adds, saying that "they made the kite of a bicycle, wheelbarrow, and train with smoke coming out".

At the entrance to the museum, a giant Chinese dragon head with a 28-meter-long tail swinging from the ceiling catches the eye.

"Here, you can only see 16 meters of its tail. The rest is on the shelves as we don't have enough space to display it all," he says.

One of the most attractive Chinese kites in the collection is one shaped like the head of a girl. Her long hair forms the tail of the kite.

Liu Zhiping, an organizer of the Weifang International Kite Festival, a global event held in Weifang, Shandong province, known for its kite-making tradition, presented the kite as a gift to Akoz several years ago.

"Liu Zhiping is a highly prominent character who has worked hard to promote Chinese kite culture around the world and I am proud that he is my friend," he says.

He says the art of designing a kite has been forgotten, and as a result, many ancient types of Turkish kite have disappeared.

Kite culture arrived in Anatolia in the 13th century during the Ottoman era, but never became as popular as it was in China, he says.

Akoz has been working hard to introduce this art to Turkish children by hosting workshops on the ground floor of the museum.

"We used to organize daily workshops for up to 100 pupils at once. Our weekly schedule used to be full before the pandemic," he says.

"But when the outbreak in Turkey erupted in mid-March, my sole source of income came to a full stop," he notes, adding that Ibrahim is the first visitor the museum has received in two days.

As for the future, he seems reserved in his hopes, saying, "even if the pandemic was over, there is still no space left in the megalopolis for kites. Therefore, I am calling the city authorities to open some green areas for children and to support the art of kites."