A refuge for bookworms & the broken-hearted

Asked if he was lonely, Wu gazed at the questioner and blushed after downing half a cup of his curative liquor.

"My son's all I've got. I earn money for him or I die. Forget about loneliness; it's no big deal. Of course there's meifeng jiajie beisiqin (a poetic line referring to missing one's family especially during festivals). But no matter how hard life is, I just need to get on with it so I can save money for my son."

Then, as his eyes became watery, Wu added:"After all, books teach me that loneliness is my fate."

In January last year Wu unusually went back home for the Spring Festival. He did not return until June because of the COVID-19 lockdown. However, the pandemic had reduced orders for shoes, so many shoe factories had closed, and he, like many migrant workers, decided to return to his hometown.

On June 23, a Wednesday before the Dragon-Boat Festival, Wu, aware that he might never return to Dongguan, went to the library to return his 12-year-old library card and get his 100 yuan security deposit back.

Librarians at ground-floor reception were inundated with similar requests at the time, and had a few thousand yuan of cash on hand at the desk every day, Wang Yanjun, a librarian, said.

The day Wu went there, Wang, on staff since 2004, was at the reception desk, where she also worked on Mondays and Fridays, otherwise working on the third floor. One of the most popular programs she had organized, in the year she started working there, was free Cantonese lessons.

"Our chief librarian requires us to take the receptionist shifts to know better about our users," she said.

She often saw Wu at the library, and the two had discussed at length A Dream of Red Mansions written by Cao Xueqin in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), both having read it three or four times.

"But our views on the novel are very different," Wang said."I understand it from an aesthetic perspective, about private lives in ancient times, but he looks at it from a political angle."

That Wednesday when Wu went to the reception desk his 12-year-relationship with the library, its books and its staff loomed large in his mind. Taking out the card and rubbing it against his shirt, he thought again about what he was about to do. One hour passed before he finally made his decision.

Wang, sensing his hesitance as she took care of the paper work, took out the library's comments book and asked Wu to leave a comment.

"I've worked in Dongguan for 17 years, and been reading at this library for 12 years," he wrote."Books enlighten people with only benefits. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a lot of factories have closed, migrant workers cannot find jobs, and we choose to go back to our hometowns. Thinking about all my years in Dongguan, the best place for me has been the library. As much I want to stay, I cannot, but I will never forget you, Dongguan Library. All the best for the future. Enlighten Dongguan and enlighten migrant workers."

Another librarian, moved by the comment, took a photo of it and posted it online, and before long it was doing the rounds of the internet and moving many more people.

"Before long many more people were using the library and applying for membership," Wang said.

"I'm very proud of my librarians," Li Donglai, the chief librarian, said in an article in the academic periodical Library and Information Service.

"We've tried to create a good working environment and atmosphere. Librarians can work hard and enjoy a rewarding life. The goal is to nurture peaceful, friendly, wise and respectable librarians.

"Wu Guichun is not an accident or an aberration but rather the result of years of professionalism and the idea of equal service, which has been widely adopted by libraries around China."

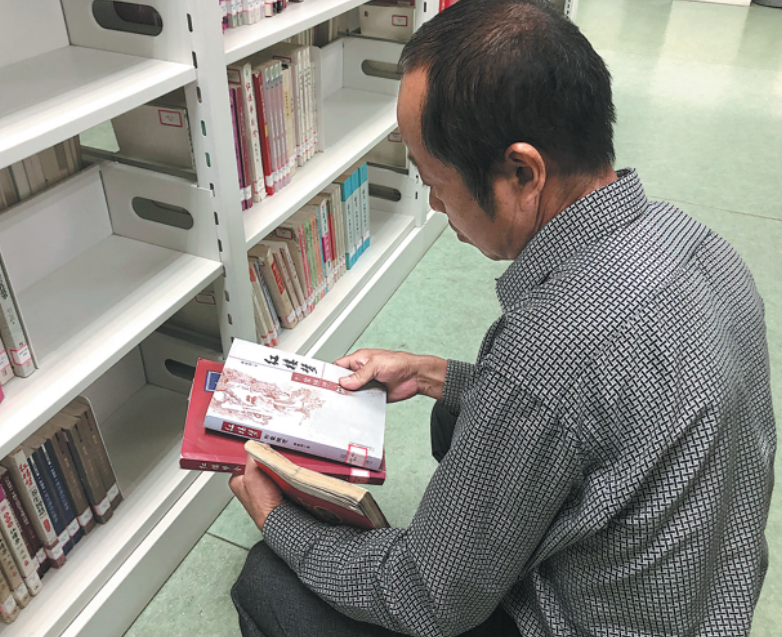

On a Wednesday afternoon, more than half the seats in Dongguan Library were taken by readers. Many were studying English, law, and finance for examinations. Others were reading literature and studying courses online.

In the reading room on the ground floor four people sat before a long desk. A young man wearing a white shirt was reading an English book. A gray-haired man in coffee-colored coat, his gray trousers rolled up to the knees, was reading a book with a red cover. A pair of sports shoes lay nearby, his bare feet on the floor.

For years libraries in China have promoted an ethos of being open to all. In 2016 a reader suggested that Hangzhou Library in Zhejiang province stop people who earned a living by collecting street junk from entering because their clothes were dirty and they smelled.

In response, the chief librarian, Chu Shuqing said: "I have no right to stop them reading here, but you have the right to leave."

Dongguan Library had similar complaints. "We have toilets upstairs, but it would be disrespectful to ask them to wash themselves, so we simply asked complainants to move to other seats," Wang Yanjun said.

She recalled the instance of a mother and daughter showing up in the comic library, the girl 5 or 6, her clothes dirty and her hands soiled.

The mother told Wang she had been the victim of beating by her husband, and she and her daughter had fled the family home. The librarians took pity on them and began to buy meals for them and allow them to stay in the 24-hour library during nights.

They stayed in the comic library for more than a week until Wang asked the woman whether they should help her to contact social workers. The woman smiled, and the two disappeared the next day.

Ten years has passed, and Wang says she has often thought about them, blaming herself for handling the matter poorly.

"Perhaps I shouldn't have mentioned social workers," she said.

In an article titled Library: Warmth and Hope, Li wrote: "For many marginalized people in cities, public libraries offer not only an intellectual and spiritual haven, but are a physical shelter as well."

Wu said reading has greatly changed him. "Reading gives me a lot of help in terms of personality, mentality and vision. Otherwise I'd be a lot more irritable."

In October he went back to his hometown and found that although his granddaughters wanted to read books, there was no book available in the village. So he decided to spend a 6,000 yuan book coupon donated to him and mail all the books back to his hometown. "My current goal is to build a small library for my hometown," he sad.

As a result of the publicity generated by his Dongguan Library comments book entry, Wu eventually received an offer of employment in the city, but the job did not work out and he and his employer went their separate ways after four months.

When China Daily spoke to Dongguan Library's most celebrated member in November he had ceased visiting the library because with the fame he had gained he had been inundated with books that people all around the country had sent to him. More recent reports said he had returned to his home province of Hubei.