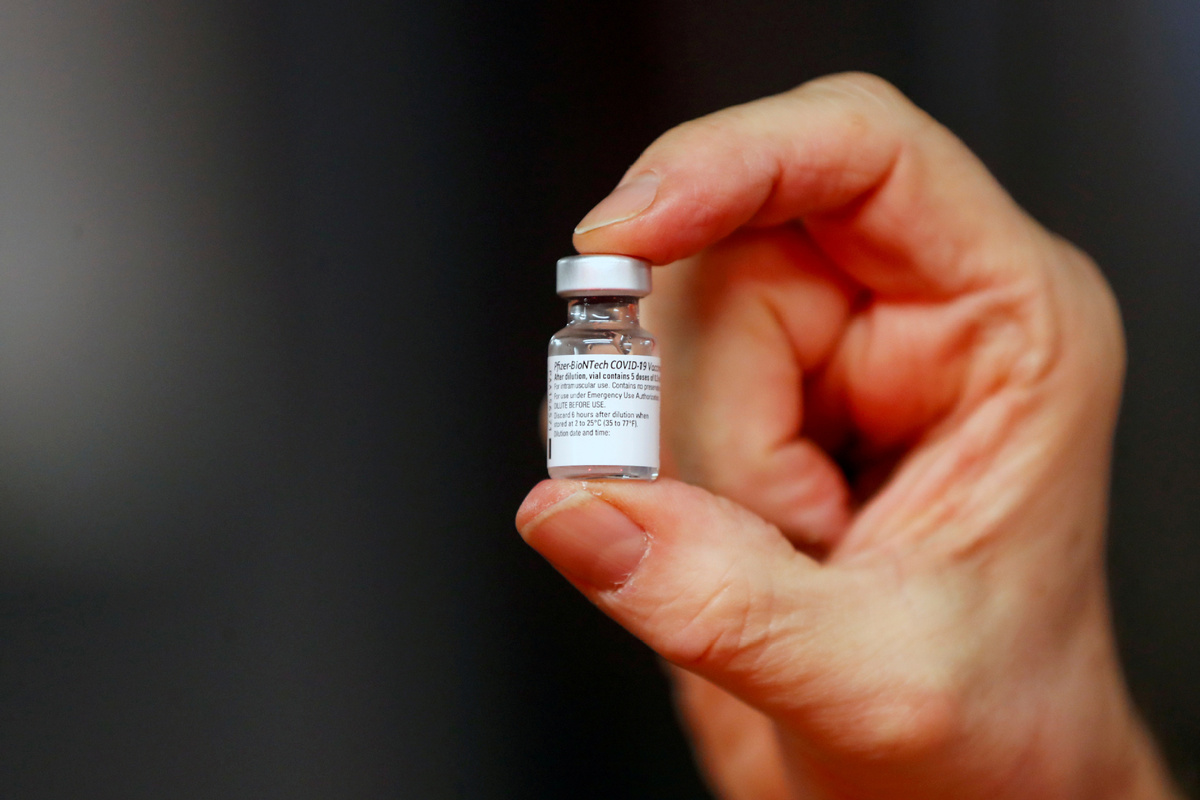

Single-dose concerns raised in UK

The United Kingdom's chief scientific adviser said the UK will look "very carefully" at recent COVID-19 vaccine analysis out of Israel, which suggests the level of protection provided by one dose of the Pfizer treatment is notably lower than first indicated in trials.

Israel's health authorities provided some of the first real-world data regarding COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness on Tuesday, releasing figures that suggest the chances of someone being infected by the virus decreased by 33 percent after receiving one Pfizer shot.

This compares unfavorably with clinical trial data, which found the Pfizer vaccine was 52 percent effective after one dose, and 95 percent effective after two.

The analysis could have implications for the UK, which has opted for a strategy that involves delaying second doses beyond vaccine manufacturer recommendations, in order to provide a larger proportion of the population with the first shot.

"We need to look at this very carefully, we just need to keep measuring the numbers," UK Chief Scientific Adviser Patrick Vallance told Sky News on Wednesday.

Real-world practice

"When you get into real-world practice, things are seldom as good as clinical trials."

UK Health Minister Matt Hancock said on Thursday that soon-to-be released data supports a 12-week dosing schedule for Pfizer, according to Reuters.

Experts have eagerly awaited early vaccine data from Israel, which has impressed with the speed at which it has inoculated more than one-fifth of its population.

Israel's National Coronavirus Project Coordinator Nachman Ash told domestic broadcaster Army Radio that the first dose is "less effective than we thought" and that data on effectiveness was found to be "lower than presented by Pfizer".

"Many people have been infected between the first and second injections of the vaccine," Ash said.

But Vallance said more information is needed before firm conclusions could be drawn, adding the first dose will not provide much protection whatsoever within the first 10 days, as the immune system is yet to develop a response. Also, some people are likely to have contracted the virus prior to inoculation.

"I don't know exactly what Israel are looking at," he said. "If they are looking at the total period from day nought, then that doesn't give an exact comparison (with the data)."

Stephen Evans, who is a professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, cautioned against reading too much into the figures.

"The reports that have come from Israel are insufficient to provide any evidence that the current UK policy," he said.