For city's darkest day, justice is still to be dispensed

"On May 30, 1921, I went to bed in my family's home in the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa," Viola Fletcher, 107, told members of a congressional subcommittee in Washington in May. "I felt my sleep that night was rich, not just in terms of wealth but in culture, community and heritage. My family had a beautiful home, we had great neighbors and I had friends to play with. … Then a few hours (later), all of that was gone."

Still being able to "smell smoke and see fire", Fletcher, who has lived long enough to be called Mother Fletcher by all who come into her audience, had traveled all the way from her home in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to Washington, so her story could be heard, and the century-old damage done to her and her people could be mended in the slightest possible way.

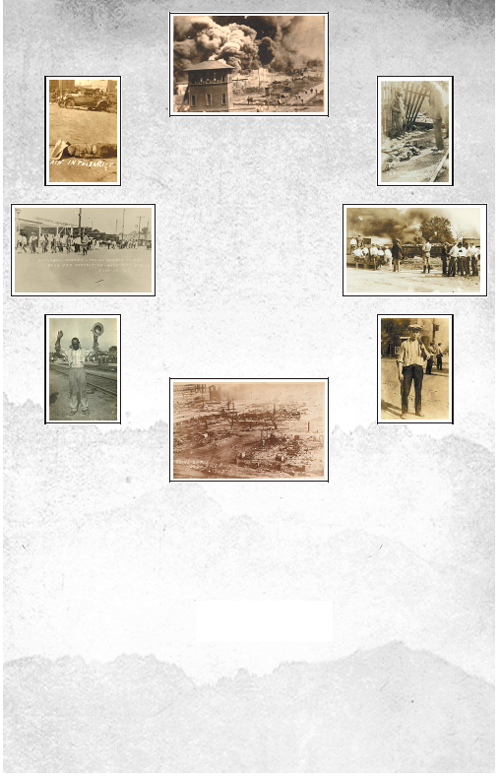

In searing detail, Fletcher recounted the killing of her people and the burning of her community by white mobs on May 31 and June 1 of 1921, as seen through the eye of a 7-year-old. Known as the Tulsa race massacre and perhaps the most horrendous racial violence against black people on US soil in the past century, the event led to the destruction of a 35-square-block neighborhood known as Greenwood District in North Tulsa. In the aftermath, more than 10,000 black Tulsans were left injured, homeless and destitute. It is estimated that as many as 300 were killed, the whereabouts of their remains largely unknown.

"I am 107 years old and have never seen justice," Fletcher told her listeners on May 19, referring to the fact that no one has ever been held accountable and none of the victims compensated by any level of US government. She was joined in the US Capitol by her 100-year-old brother Hughes Van Ellis and through videoconference by their fellow black Tulsan Lessie Benningfield Randle, 106. All have spent their life in Greenwood.

Today it would be hard for anyone not there in the years leading up to this calamity to imagine how prosperous the community once was, without the moving images captured by a black Baptist minister and amateur filmmaker named Solomon Sir Jones (1869-1936). Under his lens, impeccably dressed pedestrians and stylish cars shared the bustling streets lined with clothing stores, movie theaters and hotels. Young workers loaded crates of beer onto the back of a van, in a life that after all was well worth toasting.

"The African American history in Oklahoma is deeply rooted in slavery and linked to land that became first available for black people in the late 1800s," said Hannibal Johnson, author of the 2020 book Black Wall Street 100: An American City Grapples With Its Historical Racial Trauma.

A major black migration took place in the 1830s and 1840s when native American Indians were forcibly removed from the southeastern United States to what was to become the state of Oklahoma, he said. "Migrating with the tribes were both free and enslaved people of African ancestry, the latter owned by tribal members."

After slavery was abolished in 1865, the federal government forced native Americans to provide land allotments for blacks. In the late 1800s Oklahoma had a number of land runs and land lotteries. The prospect of land ownership attracted blacks, including some relatively wealthy men who came to Tulsa and created the black community of Greenwood District, mainly by buying land and recruiting other people of African ancestry.