Stolen identity

Tens of thousands of Indigenous Americans were sent to boarding schools in an assimilation program one bureaucrat saw as part of 'a final solution of our Indian Problem', Zhao Xu in New York reports.

Perhaps more significantly, such experiences cultivate activism in the authors themselves. "Some of the 'exemplary' students later became civil rights leaders," Emery says. "They came to see the English language as a powerful tool to speak in the interests of their community."

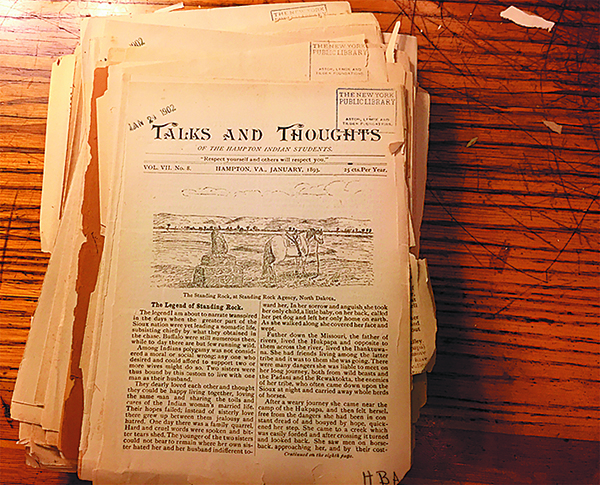

The Bender sisters were once selected as model students to travel on behalf of their boarding school, the Hampton Institute in Virginia, to attend events such as the 1904 World Fair, before both becoming involved in indigenous rights issues.

Another example is Luther Standing Bear, who implored his Indian chief father to adopt Christianity, in a letter that is part of Emery's book. He grew up to be an author, educator, actor and Indian chief, fighting for the government to change its policy toward indigenous people.

To Emery, the cultural loss at the boarding schools, irreparable as it was, had also brought out cultural awareness and persistence. And the school experiences, embodying both victimization and agency for indigenous people, were all part of their ever-evolving identity.

To prevent students from communicating in their indigenous tongue among themselves, school authorities deliberately mixed children from faraway tribes that did not share the same language, leading inadvertently to intertribal friendships and marriages. Pan-Indianism, a philosophical and political movement promoting unity among all indigenous peoples, was activated and came to the fore in the US in the 1960s and '70s.

By then the 1928 Meriam Report, commissioned by the Department of the Interior, had been out for about 40 years. The report, a comprehensive update on the state of Native American affairs, included scathing criticisms of the boarding schools, exposing their dark side from widespread use of corporal punishment, exploitation of student labor to chronic malnutrition and bad sanitation.

Yet even though the report called for the boarding school system to be abolished and to be replaced by day schools, it persisted, and even flourished, with enrollment reaching its highest point in the 1970s, 60,000 new enrollments being made in 1973 alone.

Extreme poverty, Montgomery believes, was the reason. Often unable to reintegrate with their community due to factors ranging from cultural and linguistic disparity to the lack of a basic knowledge of tribal work, the graduates were also "systemically excluded from the white-controlled job market", she says.

"They were not only traumatized but also couldn't make a living. So the next generation grew up in utter poverty."