A family's legacy returned, with interest

If the colored glazed tiles and other components used in the constructions at the Forbidden City and the Summer Palace in Beijing were to be laid on a path leading to their place of origin, the road would lead all the way to Shanxi province.

The famed glazed tile of Shanxi is an art form that dates back to the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-589) and the later Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Because of its complicated production process and high cost, the tiles were used only in building palaces and religious buildings, where budget was the least of concerns.

Among the several major workshops making colored glazed tiles in Shanxi, the one run by the Su family of Mazhuang village in Taiyuan is the most famous.

Craftsmen from this family served at two of the largest glazed tile workshops in Beijing during the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, producing tiles for the royal families' constructions.

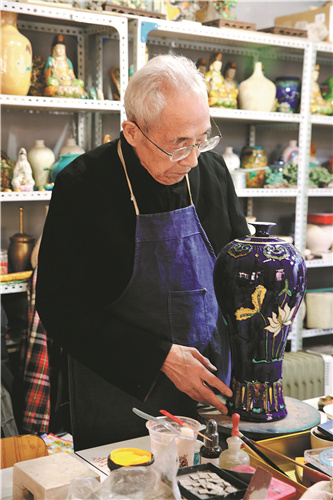

Ge Yuansheng, 82, is the seventh-generation inheritor of the Su family craft, which has been recognized as a national cultural heritage.

The craft was being passed on to only male offspring of the Su family. The tradition was broken only once, during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), when all craft work-including the production of colored glazed tiles-was regarded as an "evil legacy" of the feudal society and suspended.

The legacy could easily have died. But soon after the "cultural revolution" ended, sometime in 1979, a commune of Haozhuang village in the suburb of Taiyuan set up a workshop to produce colored glazed tiles. Ge, the commune's head, invited Su Jie, the Su family's sixth generation craftsman, to come to the factory and teach the craft to other members of the commune.

Su was so moved seeing hope for the craft's revival, he passed on his family legacy to Ge, thus making him the seventh-generation inheritor of the Su family craft.

Ge was then 39."It was from that moment that my life began revolving around colored glazed handicrafts," Ge said.