Organ donation coordinators turning death into life

After a video showing organ recipients expressing their thanks to a donor went viral in 2019, many viewers were moved to tears.

In it, the five people who received organs from the same donor, who loved to play basketball, formed their own team in commemoration.

"You gave me the gift of life, so I will take up your passion," each of the five recipients said in the video. Dressed in sports outfits emblazoned with the date the organs were donated, the five recipients all referred to themselves using the donor's name.

Still, finding willing donors isn't always easy, and behind each donation lies the efforts of organ procurement coordinators.

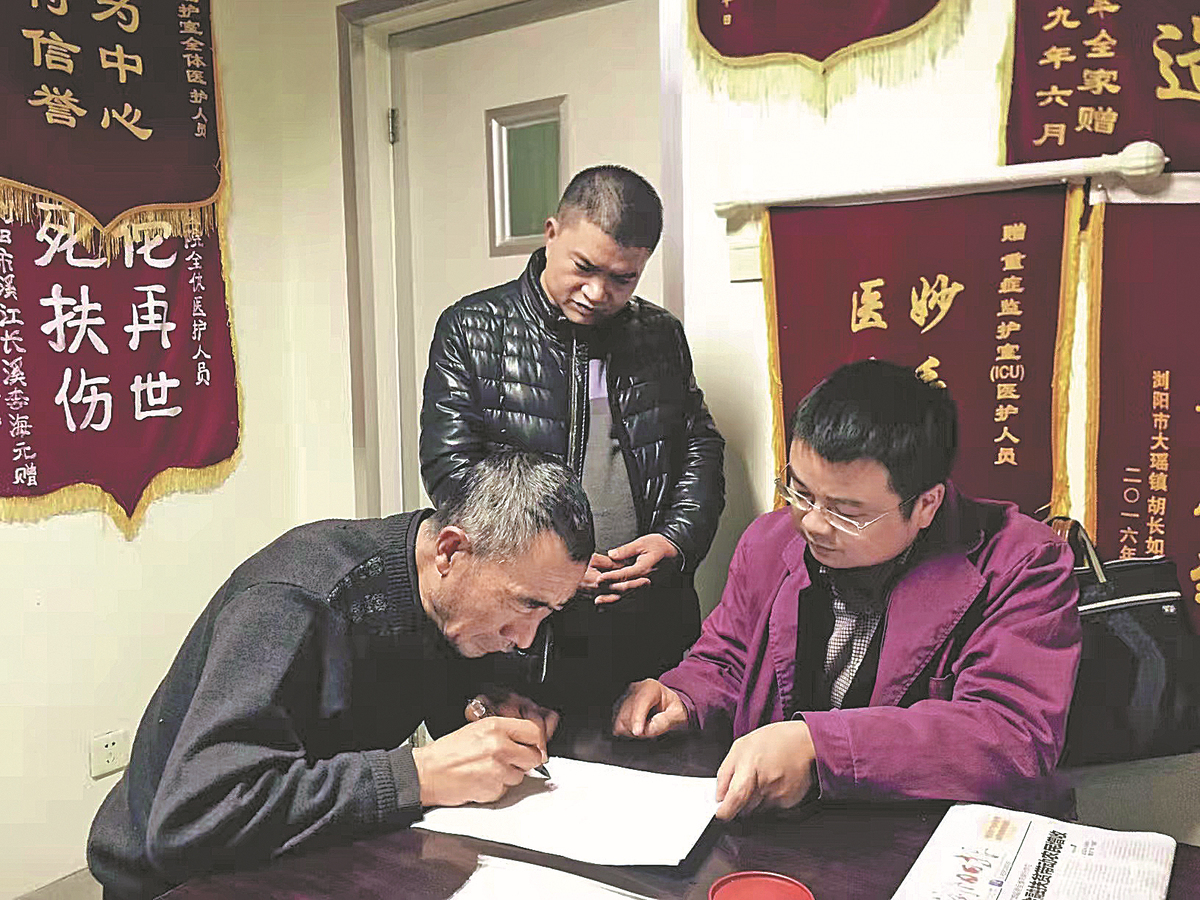

Sometimes-as was the case with the parents of a 17-year-old boy in Changsha, Hunan province, who donated his heart, liver, lungs, kidneys and corneas to seven people in 2017-the first attempt doesn't always succeed.

"It was really hard to ask them whether they were willing to donate the organs, especially at the moment they were grieving the loss of their only son," said Guo Yong, 40, director of the Organ Procurement Organization at the Second Xiangya Hospital of the Central South University in Changsha.

But in organ donation, time is critical. Vital organs can only be kept viable for a few days. As Guo and his colleagues counseled the parents, they worked slowly to build up a connection, but when they asked, the parents refused.

"They called us heartless," Guo recalled. "We respected their grief, so we chose to withdraw and wait."

Fortunately, the boy's parents eventually called back and agreed to the donation.

As a result of the traditional notion of the need to keep a body intact in order for the deceased to rest peacefully, many Chinese don't accept organ donations, said Guo, who began procurement work in 2010 while he was pursuing a master's degree.

"In 2010, we had little experience in organ donation coordination. It was a new thing in China," he said, and for the first two years, his attempts ended in frustration. "People didn't understand organ donation and didn't understand our job. To them, it was like we were organ traders."

The situation is improving, as more people are beginning to accept the idea. Over the past 10 years, Guo and his colleagues have successfully coordinated over 900 cases, and his office has grown to 10 workers from just 2 in 2010.

The donation procedure includes talking to donors' doctors and family members to review the candidates and then working with the families, hospitals and transplant programs to facilitate a successful donation and organ matching process.

"Counseling families on donation is instrumental to making the program successful," Guo said. "The ability to be kind and empathize is the basic quality a coordinator needs."

He and his colleagues have visited the 17-year-old boy's parents regularly since they agreed to the donation. They were invited to attend a sports event in 2019 in which organ recipients whose lives had been saved were participating.

"Watching recipients running, walking and jumping gave the parents relief. They said they had made the right decision to donate their son's organs to help others live," Guo said.

"Our job is like building a bridge between life and death. We are saving people indirectly. That's why most of us in the office keep going, even though we encounter many, many difficulties."

Every member of Guo's team is available by phone 24 hours a day. They respond immediately, even on holidays.

Guo suggested that authorities should release regulations on the management of organ procurement to ensure the work goes smoothly and benefits more people.

He has pledged to donate his own organs, as have other coordinators.

"Organ donation is giving life," he said. "We welcome all who want to join the work of building a bridge of life to patients on the verge of death."