Tragic legacy still matters

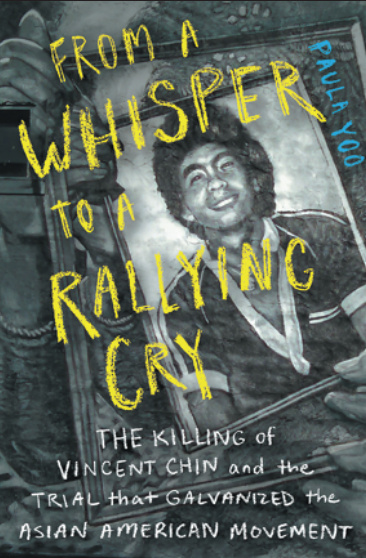

As time passed, recollection of the name Vincent Chin faded. However, his name and story resurfaced after anti-Asian hate crimes spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, says Yoo.

"I myself have experienced anti-Asian racism because of the pandemic. When I was walking down the street one day, a car drove by and someone yelled 'Chink!' at me. A white man refused to get on an elevator with me even though we were both wearing masks," she says.

In Atlanta in March 2021, a white man shot and killed eight people, six of them of Asian descent. "But yet the sheriff quoted the killer as saying he was having a 'bad day' and they did not, at the time, consider it a racist hate crime," Yoo points out.

That "bad day" comment, just like the lenient sentence in Vincent Chin's case, told the victims' families and the Asian community that "you don't count when it comes to civil rights. You don't count when it comes to the dialogue on racism in this country," Yoo says. "This is why Vincent Chin's legacy matters."

Today, the term Asian American has expanded to a more inclusive term AAPI-an abbreviation that stands for Asian American and Pacific Islander.

Yoo says that the fact that AAPI history wasn't taught in primary school was the key reason why AAPIs are often viewed as outsiders in this country.

She recalls that, a few years ago when she visited her parents' house, she found a box filled with drawings she had done in elementary school.

"I smiled at the cute images of myself in kindergarten, with my black hair and dark eyes. I clearly identified as Korean American. But as I flipped through the pages, I noticed something was off.

"The drawings of me with black hair and dark eyes were soon replaced with blonde hair and blue eyes. I was holding a tangible piece of evidence as to why representation matters not just in books, but in our schools and libraries," she says.

A recent survey reported that one out of four Asian American youths reported experiencing physical and verbal anti-Asian harassment and bullying because of the pandemic. That number could be reduced to zero if AAPI history was taught in school, Yoo says.

The media also needs to do a better job to cover news involving AAPI, says Yoo, who has worked as a journalist for the Detroit News and the Seattle Times.

"What we have seen in the social media constantly are videos of a black or brown man beating up an elderly Asian person. However, a recent survey found that 70 percent of all anti-Asian crimes were done by white perpetrators," Yoo says.

Such skewed coverage makes the minority communities look more racist than white people, explains Yoo. "That kind of treatment ignores the real elephant in the room, which is the white supremacism and systemic racism," she says.