Lessons from history

The registration certificate was quite worn out, as Dere's father always carried it. "If you were stopped by any authorized person and you didn't have the registration certificate on you, you could be subjected to immediate deportation," Dere says.

His father and grandfather worked together in a laundry for 30 years in east Montreal. The work was isolating and mind-numbing. They spoke a smattering of English and French and were mute when it came to communicating with the outside world. Economic exclusion went hand in hand with social exclusion.

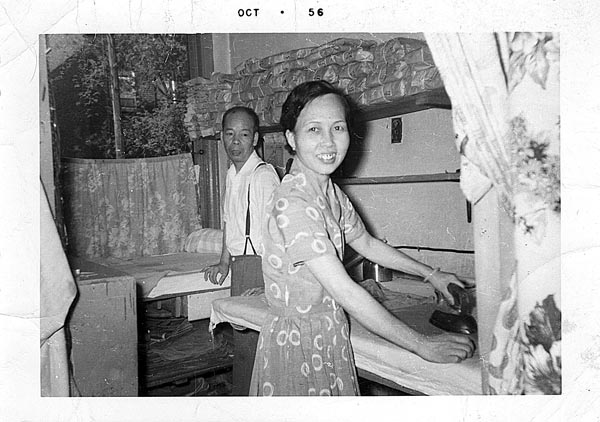

His mother couldn't come to Canada under the exclusion act. She was left in a village with her children to survive on the money her husband sent home, experiencing the Japanese invasion and later the civil war. The couple finally reunified in Canada in 1956, 31 years after they got married in 1925.

"My parents were in their early 50s when they started to share the joys and sorrows of living together again," Dere recalls.

His mother passed away when she was 101, having spent 50 years in China and 50 years in Canada. Her death came three weeks after the Canadian government apologized to the Chinese community for 62 years of state discrimination.

"She was a true Chinese Canadian," Dere says. "She was a woman warrior, determined to succeed, despite all the obstacles she was carrying within, often with overwhelming love."

On June 22, 2006, former prime minister Stephen Harper formally apologized to Chinese Canadians for the government's racist legacy. His apology was accompanied by the announcement of "symbolic payments" of $20,000 to roughly 20 surviving head tax payers and about 200 living spouses of deceased taxpayers. Many descendants continue their redress campaign for family members excluded from the 2006 settlement.

After the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1947, Chinese Canadian communities began calling on the federal government to redress Chinese workers who built the Canadian Pacific Railway and the approximately 4,000 of them who died working on its construction.

However, the Canadian government refused to talk to them with a policy of "no talk, no redress, no compensation". It took 22 years for Chinese communities to redress the head tax payers and their families.

Two national organizations-the Chinese Canadian National Council and later the National Congress of Chinese Canadians-pressured the government to acknowledge and address its history of anti-Chinese immigration policy.

"The government only made an apology because we fought for it. It was not something that was given to us. This is something we earned," says Avvy Yao-Yao Go, a lawyer and former executive director of the CCNC.