A resolute spirit

For the next eight years, Lotte's family survived with her father trading his stamp collection and Lotte taking odd jobs, including at a Chinese department store that sold tea biscuits to local foreigners. At the end of the day, Lotte recalled, she would scrape the bits of sugar at the bottom of the biscuit tin to bring home to her mother.

She utilized her English-language skills and ran errands for Chinese merchants. Every three months, she sold her thick brown hair by the ounce. She even started a little business with one of her boyfriends, turning Chinese comic books into bundles of toilet paper.

She was the first love of the most well-known Shanghailander, W. Michael Blumenthal, who later became the US secretary of the treasury in the Carter administration. She called him "Werner" and they remained friends for life.

In 1943, the Japanese ordered all the "stateless" Jewish refugees to move into a special designated area in Hongkou, which already had 100,000 Chinese residents. Living conditions became even harsher, with 10 people squeezed into one room, Lotte said. Dire poverty, hunger, disease and death were commonplace, and every summer, Lotte recalled, so was amoebic dysentery.

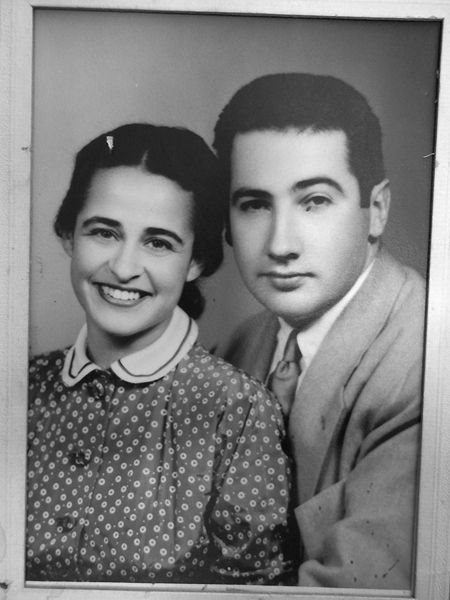

Not long afterward, Lotte's father died of kidney cancer, leaving a teenage Lotte to support herself and her mother until 1947, when they were able to emigrate to the United States. After arriving in Los Angeles, Lotte found a job as a legal secretary at the Hollywood movie studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where she met the writer Alan Marcus. They were married in 1952 and settled in Carmel, California.

That is where I met Lotte in 2003. I had been researching and documenting the history of my father's rescue activities in Vienna and learned that she still possessed the passports and visas that my father's consulate had issued.