Russian lives 'remain stable' amid conflict

Positive trend

According to data from the Federal State Statistics Service, known as Rosstat, the growth of investment in fixed assets in the first nine months this year amounted to 5.9 percent.

"Based on the data for nine months of this year, it is already clear that there will be a positive trend in investment at the end of the whole year," Reshetnikov said.

However, Western sanctions have, in some ways, dimmed hope that Russia could become a modern, prosperous nation in the near term, Vladislav Inozemtsev, director of the Center for Post-Industrial Studies, told The New York Times.

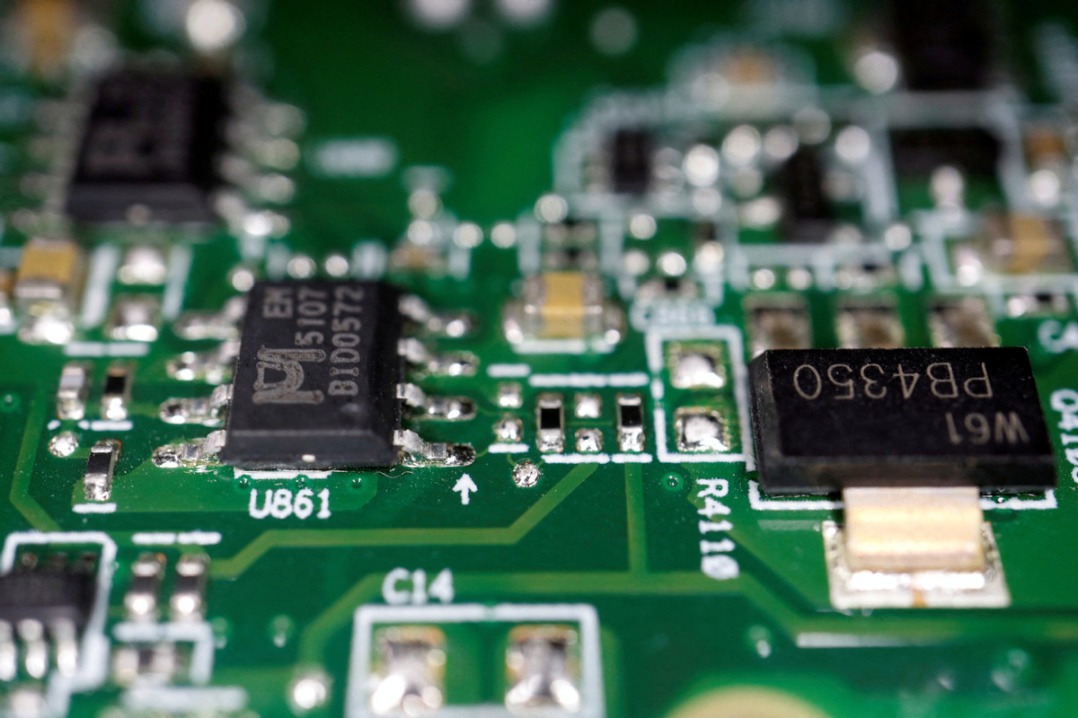

Beneath the veneer of normalcy, key drivers of economic growth like technology transfer and investment are eroding. "It's like a cake that was dropped on the table and it looks more or less fine, but inside it's all blown up," he said.

The most visible and dramatic impact has been on manufacturing, a sector that employs 10 million Russians and the centerpiece of Moscow's ambitious program to diversify the economy and reduce its reliance on oil and gas exports.

Still, Moscow had withstood sanctions better than many in the West had expected. Since February, the International Monetary Fund has revised its economic outlook for Russia upward twice and is forecasting a 3.5 percent decline in gross domestic product this year, similar to the Russian government's projections.

But the loss of investment, technology and skills caused by the sanctions is likely to echo across generations, depriving many Russians of a chance for a better economic future, experts said.

When Volkswagen launched full production cycles in Kaluga in 2009, Valery Volodin, a welder at a sprawling Volkswagen plant in western Russia, did not only get a job, but also unexpected support.

"I got paid to get trained for the job," he said. When robots replaced him, he was retrained. The job provided him 50,000 rubles ($718) a month, a payment required by Russian labor law that is the equivalent to two-thirds of his salary.

Volkswagen used to hire about 4,200 workers at the Kaluga plant, which it owns directly. Volvo and Stellantis, which produced and sold the Peugeot, Citroen, Opel, Jeep and Fiat brands in Russia, also have plants in the region. Pharmaceutical companies also flocked to Kaluga, which has a population of 1 million.

An ecosystem of suppliers and related industries sprang up to serve them, employing at least 25,000 people, said Dmitri Trudovoy, chairman of the independent Workers' Association trade union.

By 2020, Volkswagen's output alone represented about 13 percent of the Kaluga region's entire industrial production.