An eccentric approach

Painted and written art

But is it only about bamboo? "No," says Dolberg. "Because bamboo is natural, it inevitably led to the understanding of the patterns of nature and the structure of the universe. It's the gateway to understanding the whole thing."

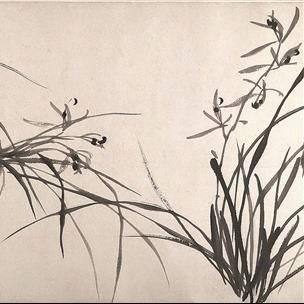

Yuan Dynasty painter Li Kan (1245-1320), whose work was featured in the Met show, must have thought so. Having traveled the country studying different varieties of bamboo, the man emerged to write his own treatise on the plant, and to give them highly realistic painterly renditions in which the sun-dried, faded tips of the leaves were treated with a graded ink wash.

By this time, bamboo had long entered the canon of literati painting and as such should by no means be treated lightly. That's why painterpoet Zhao Mengjian (1199-1264) had composed several long poems on how to paint bamboo and plum blossoms — the latter, blooming in late winter and early spring, contains an apparent symbolism for those who believed that "every winter has its spring", to quote a US writer.

In case one doesn't know, the term "literati paintings" loosely applied to works by the society's highly educated members who generally approached painting in the same way as they did calligraphy and poetry-writing, often as expressions of subtle, permeating thoughts.

Zhao, a master calligrapher, later transcribed these poems, composed on disparate occasions, onto a long, horizontal scroll of artwork that can be viewed as one holds it in hand and gradually unrolls it from right to left.

The piece's inclusion into the Met's show serves a deliberate point, says Dolberg. "Bamboo painters would often talk about the fact that the strokes they used to paint bamboo are quite similar to the ones they adopted for calligraphy." That is, similar in appearance, same in spirit.

Think about the animated, ink-soaked brush, from under which elegant characters are fast emerging alongside plum blooms and buds whose depiction requires "barely connected" strokes as fine as "a bee's whisker", to use Zhao's own words. In both cases, spontaneity comes from study, and dynamism from deliberation.

Of the eight colophons attached to Zhao's piece, five were composed by people who were closely associated with Zhao and with one another, between 1267 and 1288. (Colophons here refer to commentary writings usually made by those into whose possession the original piece had fallen. Either taking up a place within the piece or attached to its end, colophons are often works of calligraphic art in their own right and accumulatively provide a record of its history.)

Affectionate posthumous tributes, the writings have collectively painted an image of a man whose devotion to art never tempered with his generosity when it came to gifting friends with paintings. He was sorely missed by his men.

Another piece featured by the show and drenched in similar communal spirit was an over 6-meter-long hand scroll painted in 1505 by Lu Fu, known by his contemporaries as the plum-blossom painter. It was commissioned to commemorate an afternoon a man named Zhang Ling spent with Shen Zhou (1427-1509), a Ming Dynasty scholar who by that point had reached the pinnacle of his fame, as a man who was prescient enough, noble enough and — as some might like to point out — wealthy enough to have never attempted to serve the government.

After the painting's completion, Shen inscribed a poem on it, and was followed by other prominent members within his literary clique who played a game by following the same rhymes — we know the story because one of them had recounted it briefly on the painting.

Providing a magnificent example for the interplay between painted and written art, these inscribers nestled their calligraphy between the flower-laden boughs, sometimes allowing one particular stroke to dally with a delicate petal, as Shen had done.

Like the jade-like petals shimmering in flooding moonlight, the painting responds to the glowing additions of these big names through its own beauty. Rather than painted on, the white flowers and the snow that chills their fragrance were brought forth by the painter who left these areas untouched, choosing instead to deluge the background in an icy, consistent blue that contains no brush marks and never encroaches upon the flowers that seem to have transpired out of it.

"How Lu Fu did it was an ongoing mystery. Most scholars believe that he must have applied a certain substance — something nonabsorbent mixed with water — to the petal areas before applying the blue, which, as a result, would simply stay out of those parts," says Dolberg. "But this would have been very difficult to manage over such a long, complex composition."

Equally if not more remarkable is the fact that the painting, which by virtue of being a hand scroll is supposed to be viewed bit by bit, was actually painted with its entirety in mind, and therefore is best appreciated completely laid out, as it was displayed at the Met.

"If you step back and look at the whole thing together, you start to realize that instead of comprising multiple vignettes, the painting is in fact an up-close view of a horizontal slice of one blooming tree, with its sprawling branches coming in and out of the frame all the time," says Dolberg.

"It's very rare for an ancient Chinese painter to think of the hand scroll as a kind of long slice of a larger scene, and give it a monumentality as Lu did here."