Graceful technique that takes patience to master properly empowers enthusiasts

The fluid combination of slow, graceful movements and lightning-quick strikes easily sets taijiquan apart from other martial arts.

The earliest traceable origin is in mid-17th century Henan province, home to its first popularizer, the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) general Chen Wangting.

In modern times, taijiquan has become popular among Chinese of all ages, genders and ethnicities. Its mental and physical health benefits have also garnered enthusiasts across the world.

Taijiquan, influenced by Taoist and Confucian thoughts, as well as traditional Chinese medicine, builds upon theories of bodily energies, the yin and yang cycle and the unity of heaven, earth and man. Unlike combat-oriented martial arts, it focuses on internal development, and is characterized by set exercises, breath regulation and the cultivation of a righteous, neutral mind.

Taijiquan's basic movements center upon wubu (five steps) and bafa (eight techniques) with a series of routines, exercises and tuishou (hand-pushing skills performed with a counterpart).

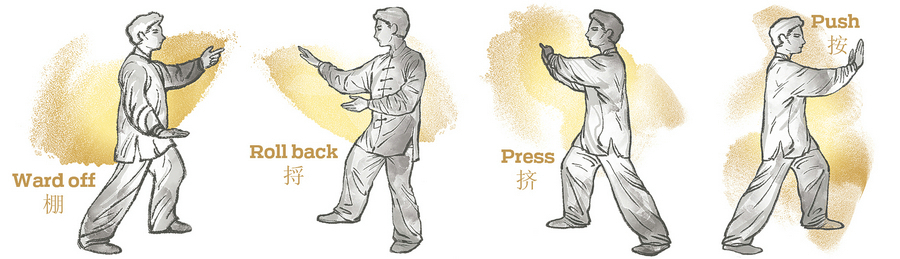

Bafa refers to peng (ward off), lyu (roll back), ji (press), an (push), cai (pull down), lie (split), zhou (elbow strike) and kao (lean). It represents the eight fundamental methods of training the body's power, and lays the foundation of all the skills and techniques of taijiquan.

Correct practice of taijiquan must be built upon a clear understanding and identification of the power. The study of the eight techniques is central to understanding and applying taijiquan's hand-pushing drills.

Practitioners must fulfill all the requirements of the postural and energy system before they get the hang of executing the trained power.