Desert town in China retains old India link

A desert town is perhaps the most prominent among locations in China that still reflect its links with India in ancient times.

Dunhuang in today's Gansu province in northwestern China, where a trove of Buddhist artwork was created over centuries (fourth to 14th), tells that story.

The town, on the fringes of the Gobi, shows other signs of the confluence of cultures, including Islamic. It was a military garrison during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), with the Crescent Moon Lake — a blue-and-green patch amid the "singing dunes" of sand that appear beige or gray, depending on the time of day or night — serving as an oasis for trader caravans. Bactrian camels are sighted there as part of present-day tourism.

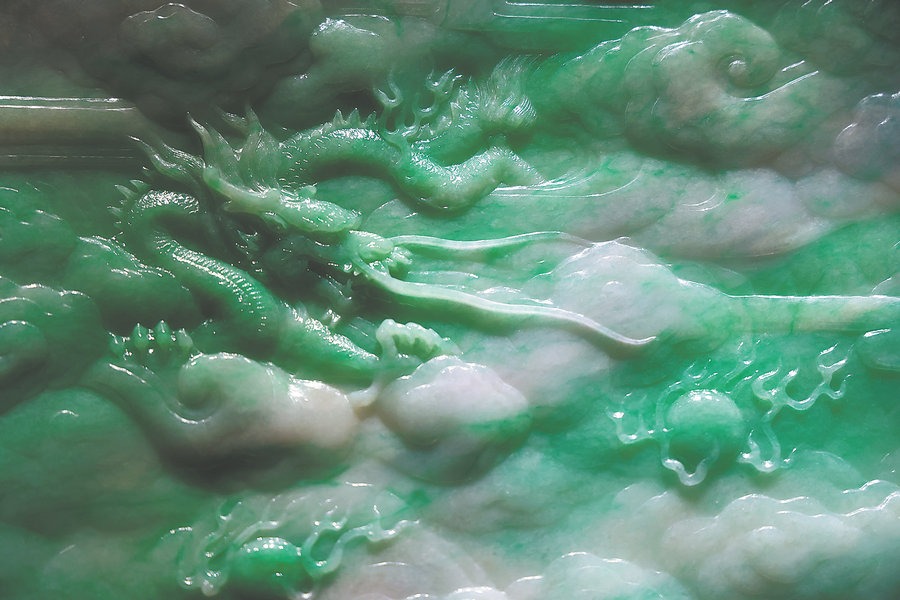

But the area's top draw, the Mogao Grottoes, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, built on mounds and painted with thousands of Buddha figures, including sculptures, in soft pigment and mineral colors across some 45,000 square meters of wall space, reveals the extent of the Indian connection.

The 492 preserved caves, once home to meditating monks, stretch 1,600 meters long by the dry Dachuan River.

The arrival of Buddhism in China from India is illustrated: One mural depicts Emperor Ashoka, who sent his emissaries to promote the religion in Asia, praying beside a stupa. The seventh-century artwork was given a touch-up during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), tour guide Li Yaping told me on a recent visit.

The Qing era saw more repairs but not all followed the original color schemes. The site's preservation is overseen by Dunhuang Academy over the past decades.

The Tang Dynasty (618-907), heyday of the arts and crafts in imperial China, backed the Sinicization of Buddhism. Mogao witnessed the changes, Li said.

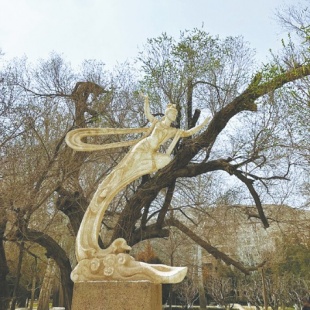

The statues of Buddha's prominent disciples, Kashyapa and Ananda, older and younger respectively, inside one cave have physical attributes that appear close to local people even while wearing dhoti, an Indian male garment. The Jataka tales on Buddha's reincarnations are mural motifs in some publicly open caves. "Flying apsaras", the celestial beings from Hindu and Buddhist mythologies, emerge elsewhere (Cave 296, for instance), and gradually become feitian (in Chinese), the modern-day cultural emblem of Dunhuang.

An exhibit at the nearby Dunhuang Museum of "eminent monks" who "came and went along the Silk Road" mentions Indian names, their travel years and work — the translation of sutras.

Chinese monk Xuanzang visited India over 17 years in the Tang era.

Other exhibits say the Han empire "started the early-stage exploration to Dunhuang by emigrating residents, establishing prefectures, counties and setting up a military defense system" at the westernmost end of the Hexi Corridor.

"The Confucianism culture in the Central Plains took root in Dunhuang, and the Indian Buddhist culture also spread to Dunhuang along the Silk Road," a museum document says.

Silk and paper were major export commodities from Dunhuang in the old trading days; major imports included woolen and linen fabrics, blood horses and rare birds (peacocks, for example), museum records show.

The grottoes house exquisite art and provide rich material to study politics (the rise and fall of dynasties and kingdoms), ethnic groups, society (a cave painting captures a prison scene) and folk customs. Dunhuang flourished under the Sui (581-618) and Tang dynasties, as well as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907-960), and saw the patronage of families that ruled the area from time to time. An artwork now used in Mogao merchandise portrays royal women of different ethnicities.

The caves contain paintings of 49 female donors (to art), including a Uygur princess, Li said.

According to the UNESCO website, "Dunhuang art is not only the amalgamation of Han Chinese artistic tradition and styles assimilated from ancient Indian and Gandharan customs, but also an integration of the arts of the Turks, ancient Tibetans, and other Chinese ethnic minorities."

From the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534) to the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), the caves of Mogao "played a decisive role in artistic exchanges between China, Central Asia and India".

Chinese, Tibetan, Sogdian, Khotan, Uygur and even Hebrew manuscripts were found within the caves, the website says.

The Library Cave, discovered in 1990, lodged tens of thousands of manuscripts.

A six-syllable mantra in ancient Tibetan characters etched on a black stone slate and a woodcut block with rune in Sanskrit, both from the Yuan era, found later at other archaeological sites in China, are among relics displayed at Dunhuang Museum.

"The 'Mogao spirit' is hard to define," Li said.