A poem of Qianlong's choosing

One particular painting seems to encapsulate the efforts of ancient rulers to gain a political and cultural mandate, Zhao Xu reports.

Different renditions

The collection received its canonization and came to be known as Shi Jing at the enshrinement of Confucius and his thoughts in the ensuing era. For two millennia, it has been an unquestionable classic and a foundational text, which not only informed and inspired, but also validated every aspect of ancient Chinese society, from family life and education to politics and statecraft.

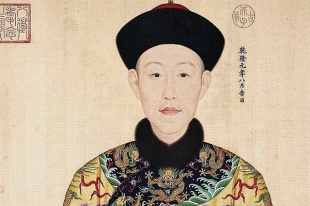

"Ascending the throne nearly a century after the demise of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the emperors of which were members of China's majority Han ethnic group, Qianlong the young Manchu emperor still felt the need to proclaim his legitimacy, by associating himself with works that marry China's age-old painting tradition to which he was utterly devoted, with the teachings of Confucianism," says Wu.

She was alluding to Qianlong's reassembling of largely-dispersed works by Ma Hezhi from the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279). A court painter, Ma spent a sizable part of his career bent over Shi Jing-related works under the royal edict of Emperor Gaozong, under whose reign a weakened Song Dynasty moved its capital from North China to today's Hangzhou city in the south. This was a teetering empire that had lost large chunks of land to, and had two emperors held captive by, the rival Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), the founders of which were genealogically linked to Qianlong's ancestors.

The fact that Shi Jing has 305 pieces and that Ma was required to paint them all meant that his artistic legacy was secured — even more so due to the impassioned efforts of Emperor Qianlong who ordered, four years into his reign in 1739, that paintings should be made depicting the works in the Shi Jing collection "based on the brushwork of Ma Hezhi". Each and every one of these paintings was accompanied by calligraphic works showcasing the book's original texts — composed by both the emperor himself and those whose brushmanship he appreciated. (Today, these works are part of the collections of the Palace Museum in Beijing and its counterpart in Taiwan.)

The effort went on for a whole six years, at the end of which, the emperor only found renewed passion to commission another mini-project: eight painted scrolls correlating with the eight stanzas of the poem July.

Among these different renditions is one that captures the gist of the poem — the longest of all folk poem-songs contained in Shi Jing. It starts with two stargazers in the far right corner, continues with some plowing and the picking of mulberry leaves, before ending with a refined scene of gentlemen gathering under a thatched roof.

If the gentlemen, enjoying tea and one another's company while being entertained by musicians, represent ancient China's literati class — educated members of the society who filled the bureaucracy, then the foremost of the two stargazers — the other, standing behind, was clearly his attendant — may be the embodiment of the man who sits above that bureaucracy: the emperor himself. The resemblance between this particular painting and one by Ma is striking to say the least.

"He's looking at one particular star — the Fire Star — whose westward shift of position in the sky was typically seen as the transition between the summer and autumn. Although winter was still months ahead, that's when people were expected to prepare for it. The ruler would be more concerned than anyone else if he were to find contentment in seeing his people 'going up to the hall and raising the buffalo-horn cup'," says Wu, quoting from the poem's last stanza.