A renegade who used the past to envision the future

"If you spent a year looking at Chinese painting before Dong Qichang, and then spend a month looking at Dong Qichang, you'll see him breaking down pictures in the same way that the cubist did. That's why some of paintings look unpretty."

Yet unlike many pioneering artists who were dismissed or even rejected during their time, Dong, thanks in part to his "savvy, powerful personality" to quote Scheier-Dolberg, was able to rise very high in the government as a scholar-official, which in turn allowed him to "operate in the elitist circles in Beijing and then back in Songjiang (modern-day Shanghai), his base in eastern China".

The collector was also publishing his own art theories, as well as collections of fatie, model letters to practice calligraphy with. "So basically he was setting the standards for what was good, what you should be studying," says Scheier-Dolberg.

These standards were avidly taken up by his disciples and their disciples, among whom Wang Shimin (1592-1680), dubbed by Scheier-Dolberg as Dong's "chosen student", and his student Wang Hui (1632-1717). It's also worth noting that Wang Shimin's grandson Wang Yuanqi (1642-1715) later became a core figure of what's known as the Orthodox School, formed by those who continued to orbit around Dong, half a century after his passing.

"Around this time, his theories coalesced and hardened," says Scheier-Dolberg.

Among other things, Dong divided the tradition of Chinese painting into two schools: the North School and the South School. On a metaphysical level, those belonging to the North School (professional painters) were believed to have gained the access to their art through hard, dayto-day practice, while their counterparts (literati painters) did so by epiphany. When it came to painting styles, the former tended to follow rules while the latter, driven by the desire for self-expression, acted more impulsively and freely with brush and ink.

But in reality, the line could be fine, so fine that such rigid categorization could appear to be mind-closing. In fact, according to Scheier-Dolberg, Dong, although "quite hard on professional painters", had generally stayed open-minded when it came to judging a specific painting — done by a professional painter or not — on its own merit.

"And it's important not to overstate his influence," he adds.

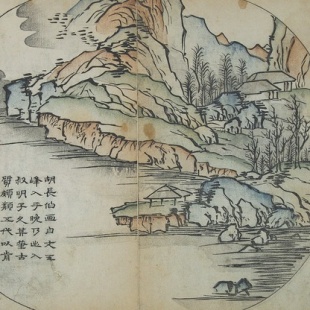

In 1679, 43 years after Dong's death, a professional painter named Wang Gai published Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, which was to become the Bible for those who were simply not fortunate enough to be trained the way Dong advocated. For them, the manual, made possible by the latest development in woodblock printing, was the closest they could get to some of the fabled masterpieces.

While some layers of pictorial subtlety were inevitably stripped in the printing process, the resulting version — in black and white — contained a crispness that had inspired at least one student — carpenter-turned-artist Qi Baishi (1864-1957), to adopt a style noted for its pithiness and modernity. By doing his part to take ink-brush painting forward, Qi, today regarded as giant in 20th-century Chinese art, could well have been a darling of Dong.

In 1630, six years before his death, Dong made an album of small paintings, "exploring the styles of different landscape masters from the 10th to the 14th centuries while imbuing each of these renditions with his own inimitable manner", to use the words of Scheier-Dolberg.

On a separate page included in the album, he reflected, not without a sense of hubris, on his ongoing effort to reinvent Chinese painting, and himself. "There are people who think the definitive Dong painting has yet to appear," he wrote.