Release program boosts Chinese sturgeon population

After construction started in 1971 on the Gezhouba Dam, a sprawling water-control facility and hydroelectric power station on the Yangtze's mainstream, the fate of the Chinese sturgeon and several other noncommercial species attracted great attention.

"At the time, China had not established a system that required major projects to be vetted for their environmental impact, and the creation of the Gezhouba Dam spurred a lot of research and discussion among scientists," Jiang said.

In the years that followed, researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and other research bodies discovered that fish species of high economic value — such as the grass and silver carp — were highly adaptable and minimally affected by the dam. They quickly formed new spawning grounds. Therefore, experts decided that the rescue efforts should be directed elsewhere.

The Chinese sturgeon and some other migratory species were not so lucky. The ancient fish spend most of their lives in the ocean but return to freshwater areas to reproduce. They embark on long journeys to reach their spawning grounds in the middle reaches of the Yangtze during the spring and summer months, when the females release eggs into the river while the males release sperm to fertilize them.

The fertilized eggs then drift downstream, where they develop into free-floating larvae. These young sturgeons eventually settle onto the riverbed and continue to grow before eventually migrating back to the ocean.

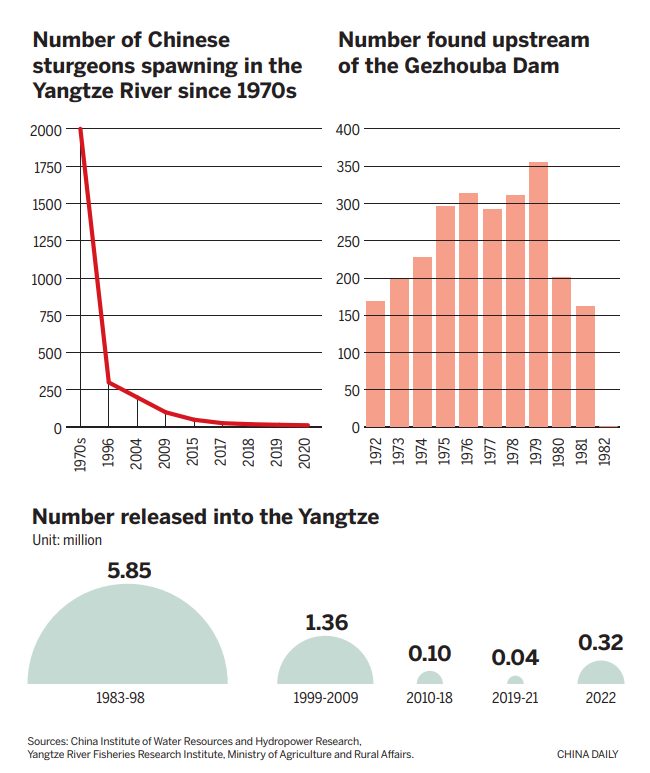

However, the Gezhouba Dam and other infrastructure partially disrupted the process. Before the Gezhouba Dam prevented fish on both sides of the facility from accessing the upstream and downstream parts of the Yangtze River in 1981, there were 16 spawning grounds spread across the Yangtze and its tributary, the Jinsha River. In 1981, only one spawning ground was discovered downstream of the Gezhouba Dam.

In 1982, naturally spawned young sturgeons were spotted in the waters near the dam, showing that the fish still managed to reproduce despite the new dam disrupting their migration path. Therefore, authorities abandoned an expensive plan to open a migratory pass through the dam and settled on more affordable conservation methods that could deliver immediate results, such as releases of fish, the creation of conservation zones and the imposition of fishing bans.

The same year, the Ministry of Water Resources established a body to carry out the releases, which later became the Chinese Sturgeon Research Institute, Jiang's employer.

"The institute is the first of its kind in the country, and it has gradually morphed into the backbone of the protection of the endangered Yangtze River fish species," he said.