NATO's eastward pivot is to interfere in regional affairs

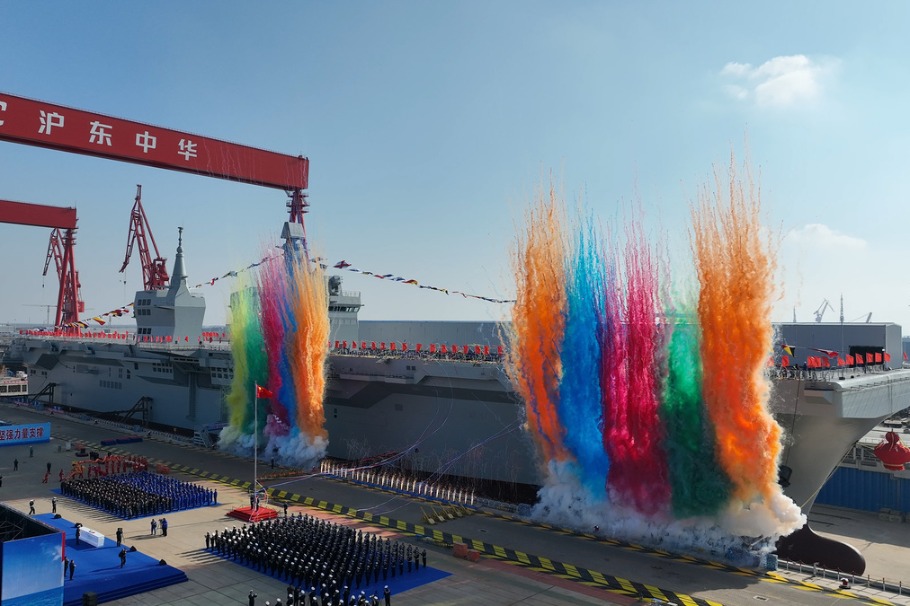

MA XUEJING/CHINA DAILY

China should stick to the vision of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security and advance the Global Security Initiative along with other countries

Since the end of the Cold War, NATO has been pushing for its transformation from a regional security alliance to a global one. With the world undergoing profound changes and the United States pivoting toward the East, NATO's turn to the Asia-Pacific is the latest development of the group's ambition to become a global alliance.

The key policy aim of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, via community building and by striking a balance between great powers, is centrality. It is reflected at two levels: securing the core position in pushing for regional integration and building the Asia-Pacific partnership network. It underscores ASEAN's central role in coordinating regional relations, promoting regional economic integration, building regional political and security frameworks and coordinating the relations between major powers in and outside the region.

However, since 2020, NATO and its members have enhanced interactions with four Asia-Pacific countries — Japan, the Republic of Korea, Australia and New Zealand — and increased the vigilance against China, threatening the security order in the region and ASEAN centrality.

NATO's shift to the Asia-Pacific is the latest development of the group's accelerated expansion drive after the end of the Cold War. Despite the impacts of the Ukraine crisis, NATO's expansion into the Asia-Pacific has been launched under the leadership of the United States, and key allies of the US in the region have started cooperating with NATO in some fields.

NATO's turn to the Asia-Pacific is aimed at countering the "systematic challenges" posed by China, including its growing economic clout, increasing military strength represented by the nuclear arsenal, its development model, and China-Russia strategic mutual trust. NATO not only includes "China challenges" in its official documents to push for an institutional shift of the group's goals, but also proactively follows the line of the US' strategic competition with China.

NATO's eastward pivot is focused on aligning with key partners in the Asia-Pacific and building a North-South pillar. NATO has upgraded its longstanding security partnerships with Japan, the ROK, Australia and New Zealand to build a de facto alliance which allows it to interfere in regional affairs and protect its interests in the region, with Japan and the ROK being the two most strategic pivots. Since Joe Biden took office, NATO has elevated its military interoperability with the two nations and strengthened the building of platforms for coordination, to give play to the two countries' leading role in institutionalizing NATO's Asia-Pacific security partnership system.

Despite NATO's Asia-Pacific pivot, the group's center of gravity is still Europe. NATO members from the Central and Eastern Europe particularly insist the group's top priority is tackling threats from Russia, and don't want NATO to have a bloc confrontation, or even conflict, with China. Key countries such as France have explicitly stated that NATO should be essentially a "transatlantic" security alliance, and are opposed to giving Asia-Pacific countries membership, or establishing liaison offices in the region.

Upholding open regionalism and multilateral coordination mechanisms represented by "10+N" have long been the foundation for ensuring ASEAN centrality in the region. However, NATO's shift to the Asia-Pacific threatens ASEAN centrality and the region's security order.

First, ASEAN adheres to constructive cooperation that doesn't target any third party, and leads cooperation in East Asia through consultative multilateralism. In contrast, NATO joins hands with its partners in the Asia-Pacific to push for bloc security cooperation based on common values to fight imaginary enemies, which seriously threatens the open and inclusive East Asian cooperation model.

Second, ASEAN seeks to strike a balance between major powers in Southeast Asia and the Asia-Pacific region by proactively developing bilateral ties with them and taking advantage of their strengths, conflicts and strategic competition. In contrast, NATO and its member states seek to restrict Russia's participation in global diplomatic events by comparing the Ukraine crisis to geopolitical tensions in the Asia-Pacific, making ASEAN-hosted multilateral diplomatic events the new wrestling ground of major powers, thus weakening the role of ASEAN as a regional mediator.

Third, NATO and its members hype up maritime security issues and nuclear threats to step up cooperation in maritime defense and nuclear weapons. The group accelerates the adjustment of supply chains to ensure economic security, while fragmenting regional mechanisms dedicated to resolving hotspot issues. This threatens the agenda setting power of ASEAN at its multilevel meeting mechanisms in a wide range of areas, as well as its strategic autonomy and centrality in the region.

To counter NATO's movement, ASEAN has reiterated its commitment to building a neutral area and striving for balance among major powers. It gives play to its strength in economic cooperation to make up for its weakness in defense cooperation and defuse the security risks escalated by NATO.

First, ASEAN is responding to NATO's expansion into the Asia-Pacific by setting peace — and development-oriented meeting agendas and reiterating its commitment to preserving regional multilateral cooperation based on the ASEAN model. It also seeks to rally public opinion against NATO, and urges it to respect the centrality of ASEAN.

Second, ASEAN is exploring how to create new opportunities by promoting the flow of production factors between itself and developed economies in Europe as well as major emerging countries in the world, and is pushing for the building of high-level and comprehensive regional free market rules. It is also expanding cooperation in subregional economic and trade exchanges and digital transformation to counter the NATO's "economic security" narrative trap by promoting common prosperity.

Last, ASEAN is, on the one hand, enhancing its collective military operation capacity based on internal political consensus, and on the other hand building and consolidating crisis management and control and defense cooperation mechanisms with regional powers to enhance its comprehensive defense capacity to hedge against the military risks from NATO.

In the face of new global and regional security situations, China should stick to the vision of common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security and advance the Global Security Initiative along with other countries, thereby contributing Chinese wisdom to building a more-balanced global security order with the UN as the core.

China should not only continue to develop comprehensive partnerships with ASEAN nations, and accelerate the settlement of maritime disputes, but also enhance collaboration with ASEAN in the digital and green economy. It should support ASEAN's autonomous development and proactively participate in ASEAN-led regional multilateral cooperation mechanisms.

Sun Chenghao is a fellow at the Center for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University. Wang Yinuo is a research assistant at the Center for European Studies at China Foreign Affairs University. The authors contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at [email protected].