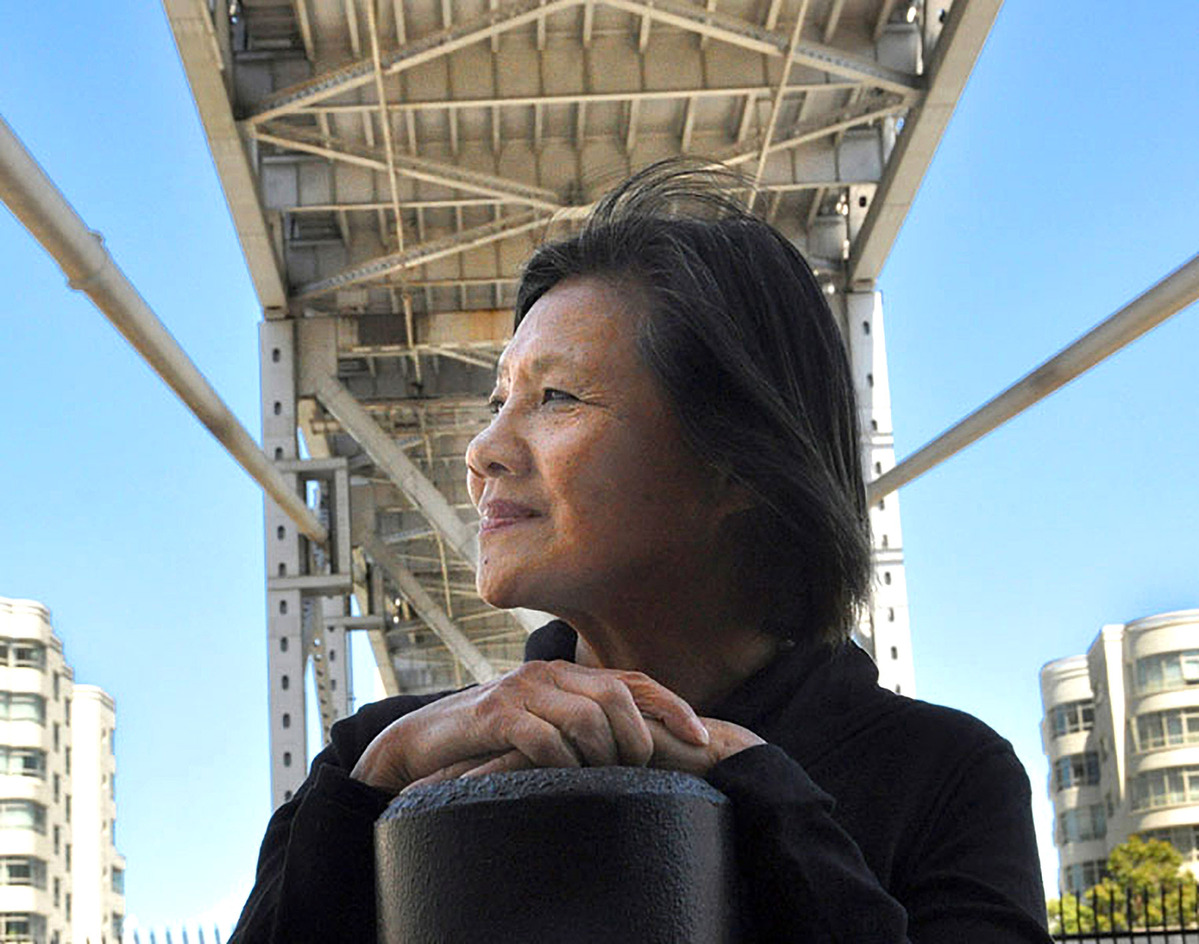

Chronicler of immigrant journeys

Genny Lim, who was recently named San Francisco's first Chinese American poet laureate, tells Mariella Radaelli that she will continue to uphold the legacy of her Guangdong-born parents and champion the cause of fellow Chinese American artists.

In the name of her mother

Though she has never lived in China, Lim says that her writing is informed by Taishan culture. For instance, one of her most representative poems, Mothertongue (2017), evokes the sounds of the Hoisanwa dialect spoken by her Chinese ancestors. It is dedicated to her mother, Lim Lin-sun, who never learned to speak English.

As a child, Lim would feel embarrassed when her mother opened her mouth in public — "speaking an extinct language with a lot of inflections, tones, and pitches". Lim Lin-sun ignored repeated requests from her daughter to switch to English, carrying on speaking in her native dialect, which "was very noticeable and idiosyncratic" even from the perspective of the family's Chinese neighbors, many of whom were from "the educated classes who looked down on us".

In order to counter such prejudice, "I had to resurrect my culture and language in a dignified, celebratory way, and with pride," Lim says. To that end, she started The Last Hoisan Poets, a small writers' collective that meets from time to time to read their works, written in both English and Hoisanwa.

Lim mentions that the presence of Nellie Wong, 90, and Flo Oy Wong, 86 — both daughters of Chinese immigrants from Tai-shan like Lim herself — in the group has led to "a renewed appreciation of and interest in the fading language and culture of our Taishan ancestors". Inspired by them, some of the younger Chinese American writers in San Francisco have started "researching their own genealogies and family histories". Lim herself leads an online memoir writing workshop, with a special focus on mining family narratives for material, for Asian American writers.

Southern voices

"Lim's poetry is an important part of the canon of Chinese American poetry, notable for how it vividly captures certain elements — sights, scents, sounds — of the everyday lives of Chinese Americans in Chinatown," says Juliana Chang, a professor of Asian American Literature at the Santa Clara University in California. "She writes poems about the unsung heroes of the community, especially women."

Chang also mentions that Lim's poems were a vital part of the blossoming of Asian American literature in the '70s and '80s. She considers the musicality inherent in Lim's poems — particularly those included in collections such as Winter Place (1989), Child of War (2003), Paper Gods and Rebels (2023) for example — as one of her hallmarks. "She is influenced by the rhythm and cadence of jazz and blues music, and has performed with various jazz musicians."

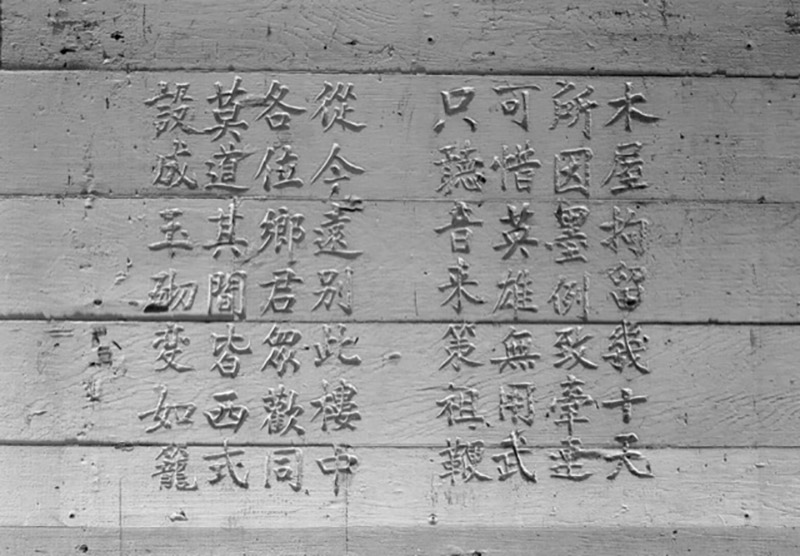

Lim herself says that the sonic rhythms of the language of her Chinese ancestors intersect with the improvisational nature of jazz music in her poems. She often incorporates elements of wooden-fish songs — a folk art form that combines storytelling with singing and is performed in a Guangzhou dialect — in her poems. Traditionally, wooden-fish songs — named after the fish-shaped musical instrument that's integral to the performances — are sorrowful ditties. The themes range from missing a relative who went abroad to desertion by a spouse.

Lim says that she finds a resonance between Afro-American blues and wooden-fish songs. "Both involve tonal scales played on a minor key and come from the South," she says, underscoring the fact that the melancholy tone in both is meant to express the hopes, despair and longings of the poor, dispossessed and marginalized communities.