Former slave labor tells of brick kiln ordeal

(Agencies/chinadaily.com.cn)Updated: 2007-06-21 08:59

RUZHOU - Up from the countryside and desperate for work, 16-year-old Chen Chenggong jumped at the well-paying factory job offered by the unknown man who approached him at the train station.

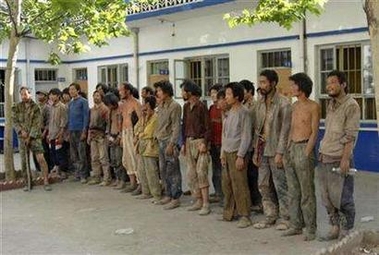

Workers stand at a police station after they were rescued from a brickworks in Hongdong County in Linfen, north China's Shanxi province, May 27, 2007. [Shanxi Evening News]  |

"I hope they are shot," Chen said of his former tormentors on Wednesday, his face, arms, legs and torso mottled with sores where the guards' blows became infected. Finally freed in a raid by provincial police, he returned home Saturday, but fear of his former tormentors remained palpable.

While Chen's story was impossible to immediately confirm, it jibes with many other tales told by former slaves over recent weeks. Apparently prompted by online protests and media reports, tens of thousands of officers have raided more than 8,000 kilns and small coal mines in Shanxi and Henan provinces, freeing nearly 600 workers, including 51 children, and detaining about 160 suspects.

China's central authorities have ordered thorough investigations.

Local governments, who benefited from bribes, taxes paid, and ownership shares, are widely believed to have protected the operations, although authorities have leveled direct accusations at only one village-level Communist Party secretary so far.

Chen's tale points to government neglect from start to finish. Having failed to qualify for upper high school, he was easy pickings for recruiters at the sprawling, chaotic, train station in Zhengzhou, provincial capital of his native Henan. Streets surrounding the station are plastered with job offerings and unlicensed job agencies, some of them believed linked to human traffickers who sell workers onto brick yards.

In response to allegations of such ties, at least one other major city in the area, Xi'an, said Wednesday it was banning all job agencies from around its railway station.

Following his March abduction, Chen said he often saw local uniformed police officers visit the brickyard in Shanxi's Hongtong region.

"They were paid off by the owner. The whole village was his," Chen said, surrounded by a small crowd of neighbors and relatives, who weighed in from time-to-time with comments and expressions of sympathy.

The 34 workers in his group included at least one foreigner, Chen said, a 20-year-old Iranian who had drifted across the border into China. He said children who looked as young as five made roofing tiles in a neighboring yard.

Food consisted of normal farmer's fare, he said, though there was never enough. "Sometimes we'd steal someone else's," he said. All workers slept on the bricks they hauled, with no showers, medical care or even haircuts.

Eight guards beat the slaves when they worked too slowly, while six guard dogs helped keep them in fear and prevent escapes, Chen said. Beatings were sometimes carried out with iron bars and wooden staves, although often guards would simply pick up a brick and smash it across a worker's head or body, he said. Workers who tried to escape were shackled, though still forced to work.

"It was very 'black'," he said, using the Chinese term for evil or corrupt.

Chen said at least one prisoner who managed to slip away reported the slavery, but no action was taken.

Many freed slaves were reported in a daze-like state from their ordeal and Chen seemed unclear about the circumstances of his release. One day, he said, the "big police" appeared and the yardseeing those who ran the yard go to trial.

Asked if he warned his son of such dangers, Chen Jinliang said: "You just never think of such things happening in a farming village."

Worries of retaliation by those connected to the yard remained constantly on the family's mind, and they agreed to be interviewed only after receiving assurances that the exact location of their homes would not be identified.

"I'm afraid of those people over there," Chen blurted out in a raspy voice, fumbling with a cigarette.

|

||

|

||

|

|