Society

Young entrepreneurs find starting up a hard sell

By Duan Yan and He Dan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-15 08:22

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

Students at a vocational school in Yiwu, Zhejiang province, work as part-time couriers for retail website, Taobao.com, during their summer holidays in July. Zhang Jiancheng / For China Daily |

Financial and bureaucratic obstacles are in the way of college graduates opening their own businesses. Duan Yan and He Dan in Beijing report.

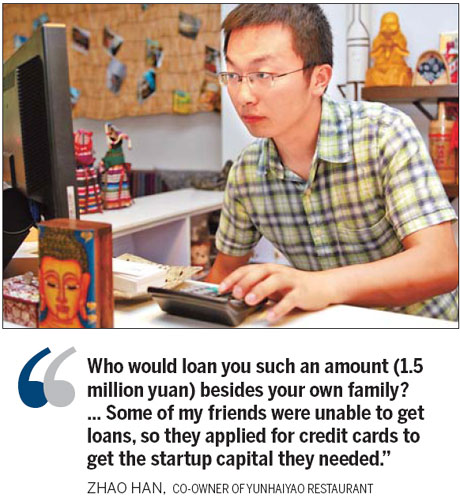

When the call went out for college graduates to relieve the pressure on China's struggling job market by starting their own businesses, Zhao Han was more than happy to answer.

He deferred his studies at the prestigious Renmin University of China for a year and began work on opening Yunhaiyao, a Yunnan restaurant he co-owns with three friends in Beijing's bustling Houhai area.

Yet, the transition from student to boss is proving far from easy for the 24-year-old, who said his efforts have been hampered by a business environment lacking in support for young, inexperienced entrepreneurs.

"I always knew there would be difficulties in running a business. But maybe I overestimated my ability in coping with the challenge," said Zhao.

More than 6 million college students entered the job market this year, joining the 800,000 still unemployed from the class of 2009, according to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

Since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, which resulted in a sharp decline in opportunities, universities and central government officials have urged graduates to launch companies.

Zhao, a guo xue (traditional Chinese culture) major at the time, was among a small number who took the advice.

Just 0.2 percent of 5.6 million students chose self-employment after graduation in 2008, according to the most recent data released by the China Higher Education Student Information and Career Center.

"The percentage (of self-employment in China) is still pretty low, compared to the average of 1 percent in developed countries," said Yu Jian, director of research at the career center.

However, he pointed out that the number of young entrepreneurs is likely much higher today "as many people branch out on their own after only a few years of employment".

The greatest challenge facing any new business is seed money, and research has shown Chinese graduates suffer a serious disadvantage in getting bank loans.

Despite preferential policies issued by the government to encourage banks to offer small loans to student startups, experts say complicated application procedures are preventing many from raising enough capital.

A survey of 4,000 student- and graduate-entrepreneurs in Jiangsu province by researchers at Soochow University this summer found that 62 percent listed funding as the biggest headache.

More than 78 percent said they relied on personal savings or help from friends and family for seed money, while less than 4 percent successfully applied for bank loans, according to a report by the Suzhou-based college's business school.

"Banks are cautious about lending to small businesses," said Yu, "and funds from charitable foundations are also limited as so many students graduate every year."

Foundations offering interest-free loans for startups also set strict application requirements, such as clear business plans.

"It's not really wise for graduates to just start their own business simply because they can't find a job," said Zhu Yongqing, a Shanghai-based project director for Youth Business China, which offers advice and interest-free loans of up to 50,000 yuan ($7,400) to 18-to 35-year-olds looking to start a business.

Zhu's office has agreed to roughly 40 loans since it opened six years ago. He said about 40 percent of the borrowers will be able to repay in three years, while 5 percent will settle the debt ahead of schedule.

When Zhao Han and his partners opened Yunhaiyao in late October 2009, they initially invested 1.5 million yuan, all of which came from friends and relatives.

"Who would loan you such an amount of money besides your own family?" said Zhao, whose three-story restaurant overlooks a 500-year-old Ming Dynasty bridge and costs about 100,000 yuan in rent every month.

"Some of my friends were unable to get loans, so they applied for credit cards to get the startup capital they needed," he said.