Ancient houses in Beijing hutong are now selling for a price that goes beyond silver and gold. Tiffany Tan and Sun Ye investigate the where, who, what and how.

Zheng Xicheng isn't exactly thrilled at the prospect of getting his hands on 7 million yuan ($1.10m) and buying his own apartment. The 74-year-old would rather continue staying in his childhood home, a courtyard house on Jiudaowan Xixiang, a hutong on the northeastern corner of Beijing's former city walls. But Zheng's elder brother, and co-owner of the property, is set on selling since he's facing pressure from one of his two sons. "His daughter-in-law with the older son told his wife, 'You should already think about how to divide our inheritance'," says Zheng, who lives in the seven-room courtyard home with his wife, daughter and a grandchild.

|

|

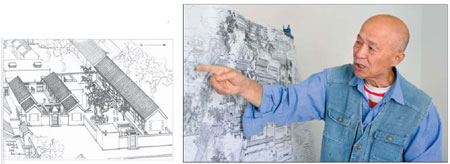

| Zheng Xicheng cherishes the memory of his childhood spent in a courtyard house on Jiudaowan Xixiang. He captures it all in a sketch published in his books. Liu Zhe / China Daily |

"My elder brother became very angry, saying, 'I'm not dead yet, but they've already come to discuss their inheritance'."

This is a common story among the owners of the Chinese capital's courtyard houses, many of which belong to the old families of Beijing.

If it were up to Zheng, a retired ivory carver, he would turn his childhood home into a museum for Beijing's courtyard homes, or siheyuan.

In the last 10 years, he has sketched the layouts of at least a hundred such homes - quadrangles usually bordered on all sides by living quarters - and published two books on the subject in an effort to preserve a piece of the city's fast-disappearing ancient residences.

The artist, who survives on his pension and a trickle of royalties, has no way to buy out his brother. So, respecting his sibling's wish, Zheng put up his home for sale in 2009. To date, he's still waiting for the right offer.

Since the market for Beijing's courtyard homes began growing in 2003, elderly owners wanting to sort out their children's inheritance have made up the majority of sellers, according to real estate agents who specialize in selling courtyard homes.

If a siheyuan has more than one owner, the consent of all titleholders is necessary before the property can be sold. Some joint owners, anticipating the disagreements that can arise among their heirs, decide it may be better to simply sell the property and divide the money now.

"When the head of the family dies, this property becomes an inheritance, and there can be many beneficiaries. In some cases, at least 20," says Miao Weilan, manager of Jiaxingjia, an agency that brokers courtyard home sales.

"Also, it's often not pre-arranged as to which room goes to whom. Even if the rooms have been assigned, who is responsible for renovating the yard? Because most homes are very old, and some leak when it rains, ordinary people can't afford the renovation and would rather sell them, then buy new apartments."

According to some estimates in the absence of official figures, Beijing has 10,000 privately owned courtyards and one-story homes, but only a fifth has clear ownership certificates or deeds. Among the eligible courtyard homes, about a hundred can be found on the market every year.

The rest are either owned by the State, and cannot be sold, or fall under State-owned companies, which can also be sold.

To spare new owners the nightmare of their siheyuan being torn down if an urban renewal project descends on their area, agents advise customers to buy courtyards located in culturally protected hutong, largely concentrated in the Dongcheng and Xicheng districts.

The most coveted, as well as the most expensive, courtyard homes are located around the Forbidden City and Houhai Lake, where the nobility used to live. Courtyards here cost as much as 150,000 yuan per square meter, so a small 200-sq m siheyuan may carry a price tag of 30 million yuan.

Courtyards on the other end of the spectrum, usually found south of the old city walls where commoners resided in imperial times, cost about 50,000 yuan per sq m.

The siheyuan market, however, is in a slump right now.

Sales of courtyard homes have fallen 20 percent year-on-year, reflecting China's economic slowdown, says Zhang Fan, president of Shunyixing, one of the biggest agencies handling siheyuan sales and renovations.

Zhang's business saw a spike in 2009 and 2010, when the agency sold more than 30 courtyard homes each year. Last year, she says, they sold 20 to 30 courtyards; this year they've only sold six so far. Individuals, both Chinese and foreigners, as well as companies have bought the courtyards.

Who are these individual buyers, and why do they put their millions into sometimes dilapidated old residences?

"Eight out of 10 are Beijingers with an affinity for courtyards," Zhang says. "For instance, they spent their childhood in a hutong. When they grow up and become successful in business, they want to return and recapture the feeling of the old days."

Zhang could have been talking about Wu Jun.

In the spring of 2009, Wu and her husband bought a courtyard home on Mao'er Hutong, on the west side of the Nanluogu Xiang shopping and dining alley, and turned it into a bookstore-cum-tea house.

"We built this primarily because of our interest in Chinese culture, not for business," Wu says. "Anyway, the property's value appreciates fast."

Now the couple is looking to buy a bigger courtyard where they can move the store, since they'd like to live in the first one with their 7-year-old son and parents.

It doesn't hurt that courtyard homes are high-yielding investments. Three years ago, Wu and her husband bought their 300-sq m courtyard for 14 million yuan. It's worth more than double that now, says Miao, their real estate agent.

Courtyard homes quickly appreciate because they are limited, endangered commodities. They also offer landed residences within the heart of Beijing, when other landed property can mostly be found outside the Fifth Ring Road.

But there are some people, like Qiao Gangliang, who are driven to own a siheyuan because of pride in their cultural heritage, as well as the desire to protect it from obliteration. The financial return doesn't factor into their equation.

"Some people will say, 'It's art, it's history, it's investment," says Qiao, senior vice-president and general counsel at Siemens China, a native of Beijing.

"I love it. I don't care if it's going to go down in value or go up in value," he says. "It's part of history, it's part of tradition, and you want to try every possible means to ensure that it stays."

That is the reason Qiao is hunting for his ideal courtyard home, preferably in a quiet, culturally protected area where there are also other retrofitted siheyuan already restored to their former glory.

Last year, Qiao visited Zheng's home on Jiudaowan Xixiang on his rounds of prospective courtyard houses available on the market.

Zheng says he was impressed by Qiao's desire to help preserve courtyard homes. Little does the elderly artist know that Qiao was equally impressed by his determination to offer his ancestral home only to buyers who will keep it true to its original form.

In a world where monetary benefits scream so loud, it is good to know there are still people who listen to a different voice.

Contact the writers at [email protected] and [email protected].