Following in the Khans' footsteps

|

|

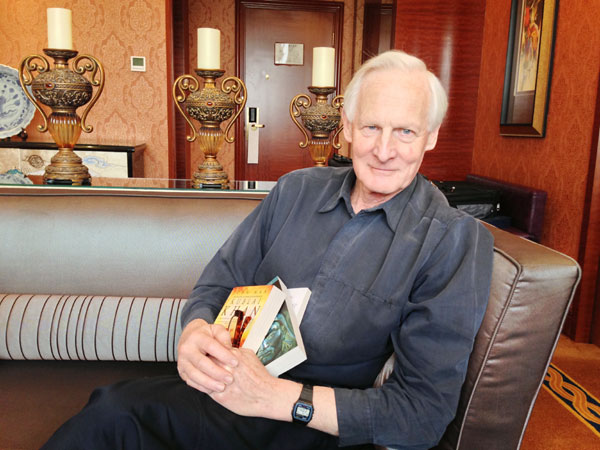

British author John Man with three of his books about the Mongolian empire and its rulers. Yang Fang/China Daily |

Marco Polo first introduced Kublai Khan and his empire to the West in the 13th century, while more recently a British author has devoted himself to the exploration of Mongolian history and culture for the past two decades.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Man, a historian and travel writer, has written three books about the Mongol empire: The Leadership Secrets of Genghis Khan, Genghis Khan: Life, Death and Resurrection, and Kublai Khan: The Mongol King Who Remade China, and his books have been translated into 20 languages.

"Genghis is a big name, internationally," the author says at the China Grassland Culture Forum in Hohhot, in January. It was Man's second appearance at the forum, which features experts from home and abroad.

"I wanted to go somewhere far away," says Man, who started studying Mongolian culture at university. "And at the time I thought Mongolia was a very remote country."

In response he studied Mongolian for a year in London and signed up for an expedition, which was canceled at the last moment. "So it became an unfulfilled dream for me."

Man became a journalist and a writer after graduation, but in the early 1990s, when his publisher asked him if he had any ideas for his next book, the idea of going to Mongolia came to him.

He published his first book about Mongolia, Gobi: Tracking the Desert, in 1997. But he realized that the real key to the Mongol empire was Genghis Khan and he determined to do further research on the historic figure.

"One of the ways to research Genghis Khan is to go to where he is buried. And the other is to find out how he died."

Man believes Genghis Khan died in a remote valley in China and he has been there twice.

"It is very hard to get to, but not too high to climb. A lot of Mongolians go there."

He failed the first time but succeeded the second time, making him one of the few Westerners to explore the valley.

He says it is important to preserve the Mongolian grasslands, calling them among the most important landforms on Earth.

He adds that the influence of traditional Mongolian culture is declining as its people adapt to modern lifestyles.

Herdsmen send their children to the major cities to become better educated, but the result is that they don't use or pass on the Mongolian language, can't ride horses, perform khoomei (throat singing), or play the matouqin (horse-head stringed instrument).

Man suggests young Mongolian people should return to the grasslands and their traditional culture.

"Everything is changing fast. It is vital for us to preserve these cultures," he says.