|

|

Many movies about Japan's 2011 disaster have been made; Japanese workers were filmed evaluating damage in the documentary "Nuclear Nation." Berlin International Film Festival |

|

|

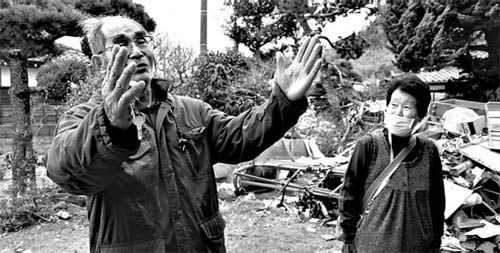

These survivors were interviewed in the film "No Man's Zone." Aliocha Films and Denis Friedman Productions |

In the annals of catastrophe cinema Japan's 2011 triple disaster has proved to be an unusually accelerated case. Within months of the powerful earthquake and tsunami of March 11 that killed thousands and caused the reactor meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, there were already enough movies on the subject to constitute an all-but-instant subgenre.

The Berlin Film Festival in February featured three documentaries on the aftermath, dealing with topics like the complications of the cleanup effort, the plight of evacuees and the resurgent anti-nuclear movement. Japan Society in New York marked the first anniversary with screenings of films like "The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom," a short documentary by Lucy Walker that was nominated for an Academy Award, and "Pray for Japan," which its director, Stu Levy, made while volunteering in the stricken Tohoku region.

This new strain of post-traumatic cinema also includes several fiction films, like Masahiro Kobayashi's "Women on the Edge," in which three estranged sisters reunite amid the wreckage of their hometown, and "Himizu," an adaptation of a manga about troubled teenagers that the director, Sion Sono, rewrote to incorporate a backdrop of actual devastation. In October, the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival showed 29 films about the earthquake's aftermath in a program called "Cinema With Us."

Some films suggest deeper impulses. "It became almost an obligation to do something about the quake, to the point that doing something else was somewhat regarded as a sin," said Toshi Fujiwara, whose film "No Man's Zone," about the abandoned towns in the Fukushima area, was shown in Berlin.

Chris Fujiwara, the artistic director of the Edinburgh International Film Festival and formerly a lecturer at Tokyo University, noted that many of the films "raise explicitly, or allude to, a very broad and rich context for understanding what the disaster has revealed about Japanese society."

Some of the documentaries that were shown in Yamagata sparked vigorous discussions, according to Asako Fujioka, director of the festival's Tokyo office. She said that the films often "reveal the unease of the filmmaker, caught between two emotions: an urge and sense of duty to record the reality, and a sense of guilt of intruding and possibly taking advantage of the victims' tragedy."

Many of the ethical questions about documenting disaster center on the difficulty of reconciling outsider perspectives with the experiences of those directly affected. With the March 11 movies these concerns may also be "colored by Japanese cultural notions of decency and shame," Chris Fujiwara said.

In "311," one of the more controversial films at Yamagata, four Tokyo filmmakers chronicle their journey to the Fukushima area. What begins as an awkward, blackly comic road trip, with cameras trained on Geiger counters, becomes even more discomfiting as they interview traumatized residents, document the retrieval of bodies and are told to stop filming.

The Yamagata festival's "Cinema With Us" program has traveled around Japan in recent months. Ms. Fujioka said some audiences, especially in the disaster zones, were moved to tears, but she also noticed a lack of interest in certain regions.

"People, especially young people, seem to want to move on now that they are not in danger themselves," she said. "There is a bit of disaster fatigue."