Beware - 'kidnappers' from cyberspace

Updated: 2016-04-15 06:36

By Luo Weiteng in Hong Kong(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

|

Ransomware culprits have turned to blackmailing victims with the data they have hacked into. The nasty business has surged since it first appeared in Russia and Eastern Europe. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

A window pops up on the computer screen warning: "Your personal files are encrypted by CTB-Locker" - some 10 minutes after Betty Xu clicked a suspicious attachment called "Terms and Conditions" in an English-language email sent from "Bothman".

With the popped-up window failing to be closed and the countdown having started right away, the Beijing-based marketing director assistant was then told to pay 3 bitcoins (about $1,300) within 96 hours to have her files unlocked.

"At the very outset, I thought it was just an advertising scam," says Xu. "Having seen all the files on my computer failing to open, I then realized it was the malicious attachment I had unwittingly clicked that had made me a victim of a cybercrime wave racing across the globe."

It's ransomware - a nasty business whereby criminals can lock up or encrypt a person's computer's data, forcing the user to pay a "ransom" or lose his or her files forever.

As the name suggests, a "ransom" is involved, mostly paid with the bitcoin - a digital currency of an anonymous nature that makes it very difficult for those involved to be traced.

Last year, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) dealt with 2,453 complaints about ransomware holdups, costing victims more than $24 million.

In Hong Kong, which ranks 6th in the region and 39th globally in terms of ransomware, up to 21 attacks are reported daily, according to the 2016 Internet Security Threat Report released by US tech firm Symantec on Thursday.

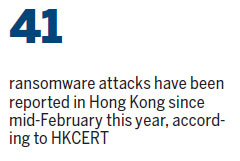

Some 41 ransomware attacks have been reported to the Hong Kong Computer Emergency Response Team Coordination Centre (HKCERT) since mid-February, with 38 hacking cases reportedly confirmed as infection by a new strain of ransomware - Locky.

A cheery-sounding name as it may be, the new variant has been on an aggressive hunt for victims since it first appeared in mid-February.

Between March 16 and 18 this year, HKCERT had noted a sudden surge in the number of Locky-related cases to 15. The number of attacks reported on a single day rose from 3 to 6.

Among local schools, more than 10 ransomware attacks have been reported in the past two months, said Albert Wong, chairman of Hong Kong's Association of IT Leaders in Education.

Leung Siu-cheong, a senior consultant with HKCERT, believes it's only the tip of the iceberg, and the problem should be much more serious as many of the cases go unreported.

Many of the victims, especially institutions, he points out, still tend to keep the problem out of view, largely because they don't want their clients or the public to think they're incapable of protecting their computer systems, client records and public interest.

Since ransomware first surfaced in Russia and Eastern Europe in 2009, dozens of software companies have advertised solutions for ransomware, but only a few have claimed success, says Leung.

Even the FBI has been quoted as saying: "The ransomware is that good. The easiest thing may be to just pay the ransom. And, an overwhelming majority of institutions just pay up."

This is also what Xu was told by cyber-security experts, who believe that her only option was to pay the "ransom" to free up her data.

Dismissing the idea of caving in to hackers' demands, Xu did manage to redo some of her files with the help of colleagues. For the rest, she still has to work overtime to restore them.

However, unlike Xu, many institutions may not be able to afford remaking an enormous load of files and records overnight, or waiting for weeks to restore servers from backup.

No wonder there's no dearth of headline-making cases involving schools, hospitals and even police departments in the US that have had their computer systems hacked into and forced to deposit "ransoms" ranging from $500 to $17,000 into criminals' bitcoin accounts.

High-profile cases that have been emerged in Hong Kong include that of The Chinese University of Hong Kong's Faculty of Medicine, which had records of more than 1,000 patients "held hostage" in 2014, with hackers demanding 0.6 bitcoin to have their files decrypted. The faculty, however, was said to have had its data backed up and just ignored the criminals' demands.

Small-and-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) which, by and large, lack the resources to defend themselves against cyber attacks, make an easy target for hackers. About 30 out of 41 ransomware incidents reported in the past two months in the SAR involved SMEs.

Although attacked victims may have no choice, but to pay up in many cases, Wong advises it's still not wise to yield to these "ransom" demands.

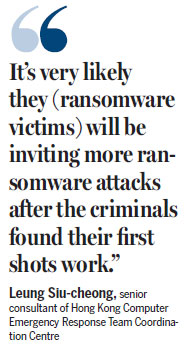

Leung says: "It's anything but a simple question of 'trading money for safety' as victims may think. But, it's very likely they'll be inviting more ransomware attacks after the criminals found their first shots work." "How much money do you have to satisfy their insatiable appetite?" he asks. "Not to mention paying the ransom cannot 100 percent guarantee you'll get the decryption key from hackers and have your data back."

Typically, it's the idea of simply paying up that makes ransomware attacks a lucrative business, warns Leung. The average amount for freeing a hacked computer or decrypting files in Hong Kong soared to 4 bitcoins recently from half-to-one bitcoin in February. One bitcoin is equivalent to $420.

Leung believes such cyber holdups are rising and will continue to rise globally. The point is such dirty business goes far beyond extortion in the form of malware, and is more of an industry chain where hackers supply ransomware with different buyers to help them launch vicious ransomware-style attacks and have victims' devices held hostage.

Data from Symantec's latest report shows that the more damaging style of ransomware attacks grew by 35 percent last year, with more aggressive attacks spreading beyond personal computers to smartphones, Mac and Linux systems.

Earlier last month, ransomware attacks were reported to have gone beyond Microsoft's Windows operating system to Apple's Mac computers for the first time with ransomware "KeRanger", which locks data on Macs so users cannot access it, being downloaded about 6,500 times before Apple and developers were able to thwart the threat.

With ransomware extortion cases spreading like wild fires, it usually takes up to 229 days for them to be detected. One can hardly bank on firewalls completely to thwart such attacks. Therefore, data backup and a "human firewall" always matter a lot, advises Fred Sheu, a Hong Kong-based national technology officer at Microsoft.

The importance of backing up data as a hedge against cyber attacks can never be overemphasized and a "human firewall" stands as the last line of defense, says Sheu.

"Data are always priceless and their loss is unbearable," Leung says. "So, do not let criminals easily prey on your willingness to click on infected links, emails and photos from unidentified senders."

(HK Edition 04/15/2016 page8)