Designers of the new world

|

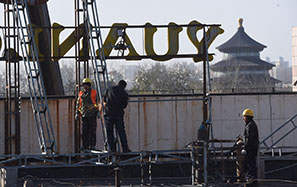

British company BDP is working on the layout of a new Ikea shopping mall in Beijing. Provided to China Daily |

For international architectural firms, rapid urbanization in China translates to 'Have tools, will travel'

In a London office, a French architect Sebastien Pollet is working on the layout of a 250,000-square-meter Ikea shopping mall in Beijing to be opened next year.

China is urbanizing at breakneck speed, and that has created business for architects worldwide such as Pollet, who works for the British firm BDP in an office transformed from a 19th century brewery house.

Each year about 15 million Chinese people, more than the populations of Sweden and Denmark combined, move from rural areas to cities. Three decades ago, 170 million people lived in urban areas in China, now the country has 700 million.

Newcomers to cities go through fundamental lifestyle changes, and they need schools, hospitals and places for leisure. The transformation is changing the lives of millions of people and the landscape of Chinese cities; and Western expertise in design, urbanization, and architecture will be part of the force that forges that change.

Pollet says the plan is for more open space and natural light in the new Ikea on Beijing's Fifth Ring Road because it functions differently from Ikea stores in Europe.

For urban Chinese, Ikea is more than a place for buying furniture. The shopping mall will have the Ikea store as an anchor to attract people, but once there they will be able to do different things. It will be a place for friends and families to hang out, experience a different lifestyle, relax and entertain themselves.

In Europe, architects and designers have fewer opportunities to turn their ideas into reality. Developing countries are experiencing a building boom, and sometimes an architectural firm is asked to give ideas on designing part of a city, or even a whole city.

"That represents a different way of thinking, which is very exciting," says Peter Drummond, chief executive of BDP.

BDP has worked on more than 10 projects in China, and now work there accounts for 15 percent of its business, compared with 1 percent five years ago.

Its business in China started with projects for Ikea in 2007. BDP has also designed stores for the Swedish company in Portugal and Poland. Along the way it has also won contracts to design other projects China. In 2011 it opened its own studio in Shanghai, and has designed various projects since then, including a tennis center in Guangzhou and eco-housing projects in Nanjing.

When BDP opened its China office it sent three people to Shanghai, one British and two Chinese, who had worked in its office in Britain. In a couple of years it has grown to an office with more than 20 people. It was fast, although Drummond says speed has never been the firm's priority. In fact, the speed of development in China is so fast that it is worrying, he says. A project that may take two or three months to do elsewhere is expected to be completed within two weeks in China.

In doing things too quickly there is great potential for mistakes or compromising on quality, says Drummond, who trained as an urban planner and has been in the business for 30 years.

Similar developments happened in Britain in the 1960s, he says. At that time, the country, like China now, experienced massive growth in car use. Every household needs to own cars, and historic cities do not fit with people's new lifestyle any more. Many highways and carparks were built, and many beautiful historic buildings were demolished to make space for them. Around the same time, in the social housing boom, big apartment buildings were built and traditional detached houses were torn down.

BDP's design philosophy is more about people than technology, he says. It is about the way people use buildings and how they move around in them. It pays great attention to the experience of a patient in a hospital, or how a seven-year-old child experiences school. All the work has that as its starting point, Drummond says. Although BDP stood firmly on its principles and challenged some of the practices in the boom years, it has made mistakes, he says. Many of its buildings were built in a rush, and 20 or 30 years later they were being torn down.

He says the firm is coping with the speed in China but insists on its own philosophy, and part of that means doing few housing projects in China. Its projects are mostly commercial and public buildings such as universities, hospitals, and retail centers. The company has also learned how to do things fast. This includes working through nights and doing a lot of drawings.

"We have learned a lot how you can do things quickly," Drummond says. "We have done things that we thought we could not do."

Technology also helps with efficiency. Architects in different countries and offices can coordinate and work on projects together. Technology has also made it easier to make changes and display projects.

Drummond says he wishes he had entered China two years earlier. Many American firms had established themselves earlier in reaction to the financial crisis, and the market in China was already highly competitive by the time BDP established itself there, he says.

Changes in BDP's business also reflect the way the work of architectural firms is changing worldwide. The firm, which is 50 years old, has about 10 offices in Britain. Specializing in social infrastructure such as schools, university buildings, and hospitals, its domestic business had been so successful that it did not expand into the international market until late in the game.

The firm changed its way of thinking about 2006, when it decided to be more internationally focused, Drummond says.

"We could either stay at home, or we follow the markets, and we decided that the best would be to follow the markets."

The change happened as the world went through a major shift, Drummond says. In the past 10 years, BDP has started to receive more inquiries from developing countries. For example, it was asked to work on hospitals and universities in Lebanon and in Libya.

Its competitors, firms in the US, Singapore and Japan, have started to travel everywhere for projects, too.

Apart from the shift of economic power, technological progress and the economics of travel have also made working together across borders possible.

It was an unusual experience for anyone to fly to Germany 30 years ago, Drummond says, but people now are used to international travel.

Architecture used to be a relatively local business, and for 30 years BDP's office in Sheffield worked on projects in the surrounding county of Yorkshire. These days people travel more, working on international projects, Drummond says, the team is much more international, and language has become more important.

Apart from China, BDP has also set up offices in India and the Middle East.

Each place has different difficulties and challenges, Drummond says. The pace in China is worryingly fast, but that in India is too slow.

The key to manage in a globalized world, Drummond says, is to be flexible.

"To expect the unexpected," he says, because if you think you know something, it will turn out that you do not.

"Acknowledge there will be surprises, and deal with them."