Abe turns his back on history

The Japanese government is continuing a tradition of refusing to address the issue of war crimes

In an interview with the Financial Times in 2005, Yuko Tojo, granddaughter of Japan's prime minister in World War II, Hideki Tojo, called Japan's aggression "a defensive war". Her justification: "Japan did not have resources."

She is not the only Japanese who justifies Japan's invasion with such a crude and shallow reason.

Her grandfather was executed by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in 1948 for crimes against humanity. Hideki Tojo is one of the most notorious of the 14 Class A war criminals enshrined - along with another 2.5 million war dead - at the Yasukuni Shrine. These war criminals make the shrine a controversial place, which a sensible Japanese politician should not visit.

Yuko Tojo is one of Japan's war-dead kin who are bulwarks against moving the "souls" of their fallen relatives from the shrine.

The ruling Liberal Democratic Party dares not settle this controversial aspect of the Yasukuni Shrine given that it counts heavily on constituencies dominated by relatives of the war dead.

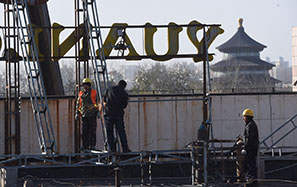

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made his third ritual offering to the shrine on Oct 17, the first day of the shrine's four-day autumn ritual. Abe did not visit in person, but he turned a blind eye to the visits by his cabinet members and LDP lawmakers.

During the ritual, about 160 members of the Japanese parliament - about 20 percent of the country's lawmakers - and several cabinet members, including Senior Vice-Foreign Minister Nobuo Kishi, Abe's younger brother, paid homage at the shrine.

"I believe it's natural to express homage to those who fought and sacri-ficed their precious lives for the sake of their country, and to pray for the repose of their souls," said Deputy Chief Cabi-net Secretary Katsunobu Kato.

Abe's dedication of a symbolic gift was likely catering to the Japanese nationalists who urged him to visit the Yasukuni Shrine in person. He paid his respects at the shrine last year when he was in opposition.

During their visit for the "2+2" meeting with Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida and Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera in early October, US Secretary of State John Kerry and Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel laid wreaths at the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery in Tokyo. They were the most senior foreign dignitaries to visit the cemetery since 1979. And the cemetery said the US officials' visit was initiated by the US and not by a Japanese invitation.

Calling the cemetery Japan's "closest equivalent" to Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, US officials said the visit was "a gesture of reconciliation and respect".

The Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery was built in 1959 to permanently keep the remains of unidentified Japanese - mainly soldiers and some civilians - who died overseas during World War II. Japanese prime ministers and conservatives always liken the Yasukuni Shrine to the US national cemetery.

Was the US visit an attempt to resolve the Yasukuni controversy by conferring legitimacy and respectability on Japan's Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery? US officials have not commented on the move.

Kishida called on the US to understand Japan's position that it has apologized to its Asian neighbors for its aggression. "Japan has been dealing with issues from the past as faithfully as possible," Kishida said at the meeting in Tokyo with Kerry, his US counterpart.

Questioned at the continuing extraordinary session of Japan's Diet, Abe said his cabinet upholds the view of history inherited from previous cabinets.

If so, why do the historical controversies remain a flashpoint in Japan's relations with its immediate neighbors?

On Sept 4, German President Joachim Gauck, accompanied by France's Francois Hollande, visited Oradour-sur-Glane, a ghost town left behind after the largest massacre in Nazi-occupied France nearly 70 years ago. The German and French presidents hugged and held hands in a solemn tribute to those French who were killed.

The visit aimed to underscore French-German postwar reconciliation, and the importance of remembering Nazi atrocities.

Even now, the search for the murderers continues. Six men from the fanatical SS Das Reich division that was responsible for the massacre have been under investigation in Germany for almost two years on suspicion of murder or being accessories to murder.

Gauck, the first serving German leader to visit the French ghost town, alluded to the pain that some in France feel because the case remains unresolved.

"When I look today into the eyes of those who have been marked by this crime," he said, "I can say I share your bitterness over the fact that the murderers have not been brought to justice, that the most serious of crimes has gone unpunished."

That's Germany's attitude. How about Japan and its leader?

Japan tries hard to wash its hands of its past rather than conducting sincere and thorough soul-searching for its own benefit and that of the victimized nations. As a result, many aspects of Japan's version of its modern history could turn out to be political time bombs, especially in its relations with China and the Republic of Korea.

After visiting the Yasukuni Shrine on Oct 20, Keiji Furuya, the minister in charge of issues related to the abduction of Japanese nationals by the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, said Japan's commemoration of its war dead was a purely domestic matter.

Japan has definitely not addressed its history in good faith.

It is no wonder that when the regular rituals are held at the Yasukuni Shrine - in spring, on Aug 15 and in autumn - the country's relations with China and the ROK are certain to sour even more.

The author is China Daily's Tokyo bureau chief. Contact the writer at [email protected].