Changing the rules of engagement in emerging market

BRICS nations play a crucial role in shaping economic resurgence

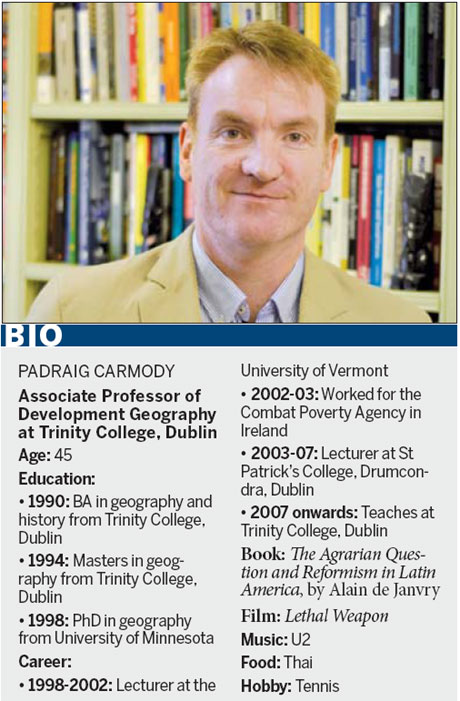

Emerging nations, particularly the BRICS nations, have through their growing engagements helped Africa chart a new course in geopolitical ties, particularly with the West, says Padraig Carmody, a well-known political geographer from Ireland.

Carmody, associate professor of development geography at Trinity College, Dublin, and the author of The Rise of the BRICS in Africa, says that these BRICS nations offer Africa an alternative engagement model, one that is characterized by policy innovations and respect for state sovereignty. The 45-year-old scholar says the real success of the alliance comes from its ability to stimulate development in Africa.

"I think some of the BRICS engagement has been more innovative and has greater development potential if it's expanded. It has at times been more respectful and attuned to the local context in Africa," Carmody says.

British economist and former Goldman Sachs Asset Management Chairman Jim O'Neill was the first person to use the acronym BRIC, which stands for Brazil, Russia, India and China, for the group of fast-growing emerging nations in 2001. The group was later expanded in 2010 to include South Africa.

Although the relationship between China and Africa has generated much attention in recent years, the influence of other BRICS countries has been studied in less detail by academics and journalists.

While world trade tripled between 2000 and 2009, it grew 10-fold between the original BRIC countries and Africa, from $16 billion to $157 billion, according to World Bank statistics.

This phenomenon is occurring against the background of BRICS countries gaining more political power globally. For example, the G20, which includes many rising powers, has apparently displaced the G8 as the primary forum for global economic discussion and coordination, Carmody says in the book.

Prior to the BRICS involvement, many African countries borrowed loans from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in the 1980s and 1990s. In return they were made to liberalize their economies, following the tenets of the "Washington Consensus".

Carmody says that this liberalization in Africa, before it was ready, has led to "deindustrialization across the continent" because local manufacturers could not compete with cheap imports and subsequently went out of business.

"I worked in Zimbabwe in the 1990s and had an opportunity to study this phenomenon closely," he says. "When the trade restrictions were lifted in Zimbabwe, the Zimbabwean manufacturers couldn't compete with the flood of imports."

At the same time, many raw material-producing African countries wanted to pay back their debt to the World Bank and IMF by exporting more goods. The excess supplies caused a drop in the prices of raw materials, thereby creating a deepening debt trap.

"Primary commodities such as cocoa and timber are price inelastic. Suddenly they (African nations) were exporting more primary commodities, but people in the Western world weren't drinking four cups of cocoa every day because there was more stock in the market. They were still drinking one or two cups as before."

He says the combined impact was deindustrialization and increasing reliance on transnational organizations. "The global free market approach is not formulated to local needs and wants. It was a top-down approach," he says.

However, this situation has changed drastically with the emergence of the BRICS nations.

Citing an example, Carmody says the Export-Import Bank of China is now the largest provider of loans to Africa, ahead of the World Bank. China is also Africa's single largest trading partner and, according to World Bank statistics, trade increased in real terms by 70 percent from 2000 to 2011.

Loans from China, however, do not impose conditions on African countries as do those of the World Bank and IMF, so allowing Africa potentially more room to develop in its own way, Carmody says.

Chinese loans often come in the form of resources for infrastructure swaps. Carmody says one positive aspect of the model is less chance of corruption, as the swap means loans are used to pay for infrastructure rather than being funneled into central government accounts.

At the same time, China's growth has fuelled a demand and resulted in higher prices for Africa's primary exports since the early 2000s.

Carmody says the rapid growth of the BRICS countries in recent years also provides lessons for African nations, compared with countries that industrialized early, such as the UK and the US.

He says one lesson Africa can learn from China is pragmatism, developing through experimental approaches, summed up by the phrase "crossing the river by feeling the stones." It was coined by the late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping to describe China when it opened up more than 30 years ago.

Carmody says China's attempt to share its growth model by setting up special economic zones in Africa is especially helpful. These zones offer tax incentives to attract more private investment and also contribute to Africa's export diversification.

At one of the special economic zones in Ethiopia, for example, there are several Chinese companies that are producing shoes, he says. Their contributions have helped Ethiopia to become an exporter of finished goods (shoes) rather than just raw materials (leather).

"I think this is the type of relation that Africa needs," he says.

Carmody says Africa can also learn important lessons from Brazil on reducing poverty and inequality.

For example, the Fome Zero or Zero Hunger program introduced under Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in 2003 has significantly helped Brazil's poorest families, a result backed by World Bank research. He says similar poverty reduction programs are now being piloted in Africa.

He says a common characteristic of the BRICS, with the exception of Russia, is that they have experienced Western colonialism or domination, which puts them in a mindset more able to sympathize with Africa.

"It brings a mindset that relationships should not be structured by force. They should be structured by cooperation, and win-win outcomes. I think there is genuine resonance here."

He says the current view of Africa as a business opportunity is a "healthier perspective" and one that has helped governments identify more opportunities.

Western governments, in contrast, have in the past treated Africa as a charity case, and a "hopeless continent" as The Economist magazine called it in 2000.

(China Daily 12/02/2013 page13)