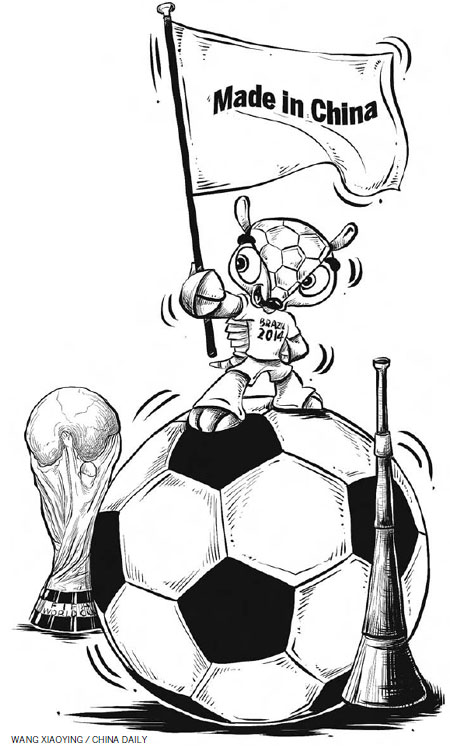

The World Cup made in China

Chinese soccer fans have to simply accept that the chances of the national men's team playing in the World Cup finals again (after 2002) is at best slim. Perhaps a joke doing the rounds best illustrates this fact: A fairy promises Chinese people to make their one wish come true. Some people ask her to make the world a peaceful place, free of wars. The fairy seems embarrassed and doesn't respond. Then some soccer fans request her to send "our men's soccer team to the World Cup finals". The fairy says: "Well, let's talk about world peace!"

But the Chinese team's absence from the World Cup in Brazil (and possibly the next few Cups) has not stopped Chinese enterprises from using the soccer craze to make "big" money.

A number of domestic enterprises have dipped their fingers in World Cup-related business. For example, Yingli Green Energy Holding, a leading renewable energy company and official secondary World Cup sponsor, is installing solar panels in some stadiums. Like other big brands, such as McDonald's and Visa, Yingli's name can be seen in the hoardings around the pitch in the World Cup stadiums.

Chinese manufacturing companies have been busy producing authorized products, such as the official match balls, called Brazuca, and miscellaneous other commodities, such as mascots and national flags. Wagon Enterprise in Dongguan, Guangdong province, which is authorized to make World Cup-related products, has produced more than 1.5 million mini-replicas of the World Cup trophy and 400 types of other products.

Given the soccer craze, Chinese enterprises are expected to make good profit from the gala in Brazil, with some researchers, including those with Moody's Investors Services, saying that the Chinese economy would benefit more than Brazil's from the World Cup. Perhaps their contention is based on Chinese enterprises' all-round involvement in the World Cup. A closer look into the role of Chinese enterprises in the production chains of World Cup-related products will, however, show that they are wrong.

Most of the Chinese companies benefiting from the World Cup are from the manufacturing sector, and, as original equipment manufacturers of major international brands, their gains are small compared with the brand owners. For example, for 2010 World Cup, Chinese companies made the vuvuzelas, which were heard across South Africa, and sold them to foreign dealers for 2 yuan (32 US cents) each, which were ultimately retailed by vendors in the host country for 40 yuan a piece (and as high as 100 yuan each in specialty stores). The Chinese manufacturer, therefore, made only a tiny proportion of the total profit.

This year, the Brazuca, the official (Adidas-branded) balls made by Shenzhen-based company YaYork Plastic Products, cost 1,299 yuan each, according to a company employee. No one knows for sure what percentage of that amount will go to the Shenzhen company, but, based on previous cases, it is likely to be tiny.

An oft-cited case illustrating Chinese manufacturers' poor standing in the global division of labor is that only about 2 percent of the profits from sales of the much sought after and expensive Apple iPhones goes to the Chinese original equipment manufacturers.

In market economy, most of the profits come from links such as designing, brand, research and development, and services - not manufacturing. For higher returns on added value, enterprises must upgrade their designing and R&D abilities, create their own brands and provide other product-related services - this is the success mantra of Apple.

Most Chinese enterprises are yet to go that far. The Chinese economy may have become the second-largest in the world, but its overall economic influence across the globe is largely based on low-end manufacturing and consumption of resources. It has become the "factory of the world", which is not the same as a real industrial power that controls the competitive production chains.

If China succeeds in its efforts to restructure its economic model and make it more technology- and innovation-driven, its enterprises will hopefully play a more active role in the global division of labor. For now, only a small number of Chinese enterprises are climbing up the ladder of global production chains.

Renewable energy giant Yingli is one of the leading Chinese companies to shine at the World Cup. Although it paid as much as $17 million to become a secondary sponsor, the deal is likely to yield positive results by making Yingli known to millions of people across the globe.

Moreover, China's electric vehicle makers won the contracts to provide hybrid buses and electric multiple-unit trains to help soccer fans travel in World Cup host cities and connect stadiums with different areas. If this trend continues, more Chinese players - not soccer players, though - could be seen displaying their skills at the next World Cup.

The author is a senior writer with China Daily. [email protected]