German manufacturing model best for China

Veteran observer believes sector still has great potential despite its high share in economy

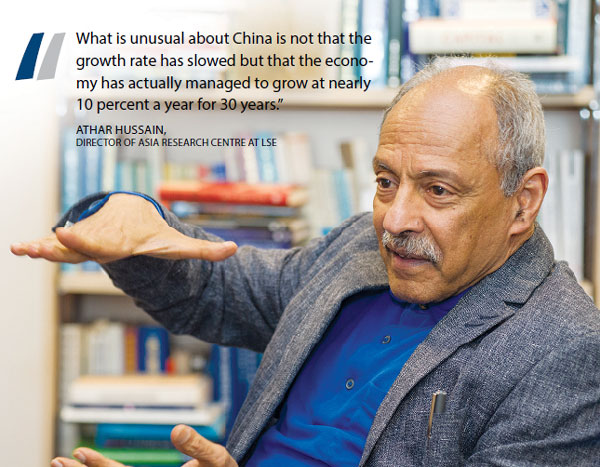

Athar Hussain is puzzled as to why everybody seems surprised about China's slowing growth.

The director of the Asia Research Centre at the London School of Economics and a veteran observer of the country's economy, insists returning to some form of normal rate was an inevitability.

|

Athar Hussain believes China will be defying the odds if its longer-term growth eventually settles between 4 and 5 percent. Nick J. B. Moore / For China Daily |

The recent slump in the Shanghai Composite share index and other factors has prompted some commentators to suggest the 7 percent annual GDP target, achieved so far this year, will be difficult to reach in the second half.

"What is unusual about China is not that the growth rate has slowed but that the economy has actually managed to grow at nearly 10 percent a year for 30 years," he says.

"Historically, we haven't seen that kind of growth experience anywhere"

Hussain, 72, was speaking in his 10th floor offices at Clement's Inn in central London. He has studied China intently since reform and open-up in the late 1970s.

He has met many key political figures behind China's economic development and during 2006 and 2007, spent a year in Beijing working as a consultant on the European Union project on social insurance with China's Ministry of Labor.

"I have been going to China on a more or less regular basis since 1987, at least two or three times a year and there have been periods when I have been five or six times."

Hussain's thinking is very much influenced by 90-year-old US Nobel prize winner Robert M. Solow and his theory that economic growth is related to technological progress, which he believes applies to China.

"When you begin the growth process, you have ample opportunity for catching up since you can continually transfer labor from low to high productivity sectors."

Hussain now argues it is increasingly more difficult for China to do this.

"If you take mobile phones for example, China might not quite have caught up with Samsung but if you look at phones produced by Xiaomi (the Beijing-based electronics maker), they are in many senses just as good.

"The gap between Chinese technology and the world's best is now not that great."

Hussain believes China will be defying the odds if its longer-term growth eventually settles between 4 and 5 percent.

"An economy cannot grow faster than the rate of growth of its productivity and one of the most rapid growth rates of productivity we have seen is Japan in the 1960s and 1970s when it was 4 or 5 percent," he says.

"The only economy that has reached a high level of maturity and still maintained high growth rates is South Korea (which even after the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s had growth of nearly 10 percent). It invested heavily in science and technology, which is a model I am not quite so sure is open to China."

Hussain believes the Chinese economy is still grappling with the problems created by the 4-trillion-yuan (588 billion euros, $644 billion) stimulus - the biggest financial injection in economic history - in the aftermath of the financial crisis, which is hampering the government's attempts to rebalance the economy toward services.

"At the turn of the century, you had the state sector reducing as a proportion of the economy and the non-state sector increasing. What we saw after the financial crisis was a reversal of the process with money channeled through state-owned enterprises causing excess capacity.

"It is not that the Chinese haven't been consuming during this time. There are more shopping malls in China per head of the population than anywhere in the world. The Chinese are consuming with great enthusiasm. It is just that other areas of the economy have grown faster."

Hussain was born in Hyderabad, India, but his family migrated to Pakistan in 1948 just after partition.

He was educated at the University of Karachi in the 1960s and while he was completing his studies there, his professor told him to meet with the French consul in the city.

"I had a conversation with him for about 20 minutes and he said, would I like to go on a scholarship to France for a year. I just said 'okay'."

He went initially to Universite de Dijon but then in 1965, he went to the UK to carry on his graduate studies at Oxford University and has remained in the country, apart from spells as a visiting scholar at MIT and Harvard in the 1980s.

After teaching at Reading and Keele universities, he went to the LSE in 1987 and became director of the Asia Research Centre just less than a decade ago.

The center, which is chaired by British economist Nicholas Stern, aims to look at Asia through the prism of social sciences.

"We are not a regional studies center but there are lot of issues that are of great importance to social sciences on a regional basis," he says.

Hussain, who co-authored a number of books including Transforming China's Economy in the Eighties, believes that if it is to upgrade its economy, it must follow Germany's 4.0 manufacturing model rather than the UK's financial services one.

"While the share of manufacturing in China is still high, I still think there is great potential there. Germany is a good role model for China. Even though the German car industry was quite advanced in the 1960s, it has kept investing and investing. They may be a high-cost producer but because of technical innovation, people are prepared to pay high prices for BMWs."

He says that because of its giant size China faces problems that do not apply to small countries like Demark or Sweden, which became evident when the global recession hit.

"If you are the world's largest trader, the growth of your export market is limited by the world's rate of growth since there is only so much demand in the world. If you are a small country you can grow at almost any rate."

Hussain, like Paul Krugman in the United States and Financial Times chief economics commentator Martin Wolf, is among those skeptical about austerity being the right medicine to resolve current economic issues.

He believes there would be little risk for even indebted countries to invest more in infrastructure so as to boost productivity in the long run.

"I think if the Italian government has no problem selling government bonds, then I don't think it would be a problem for the British government. People use this argument about passing on debt to their grandchildren. Grandchildren, however, can't finance their own debt by issuing more debt. Governments can."

Some of the major debates in economics surround French economist Thomas Piketty, but Hussain prefers the work of British economist Tony Atkinson looking at the economic consequences of inequality, which are also relevant to China.

"I do think inequality is going to become an important economic and political issue. If you look at the bonus of managers in the financial sector, they are earning billions of dollars. Some work hard but a lot of the roles just involve sausage machine processes, no real fresh thinking but repetitious forms of calculation," he says.

Hussain is far from a doom monger about China but he believes there is an urgent need to restructure state-owned enterprises and move away from an investment-intensive model that creates excess capacity.

"I don't really see the problem of a crash but the system still encourages huge wasteful and excessive investment. This needs to be addressed."

Bio

Athar Hussain

Age: 72

Director and professor, Asia Research Centre, London School of Economics

Education

BA (Hons) and MA, University of Karachi, 1960-64

Universit de Dijon, France, 1964-65

MPhil and MLitt, University of Oxford, 1965-70

Diploma in Modern Chinese (Cambridge Board)

Career

Lecturer in economics, University of Reading, 1970-71

Lecturer in economics, University of Keele, 1972-80

Senior lecturer in economics, University of Keele, 1980-86

Reader in economics, University of Keele, 1986-95

Senior research fellow, LSE, 1987- 2007

Director and professor, Asia Research Centre, LSE, 2007- present

Books: Growth Theory: An Exposition by Robert M. Solow; and Inequality by Anthony B. Atkinson

Film, Casablanca (1942, director Michael Curtiz) "I still see it and there remains something about it that remains very engaging."

Music, Ode to Joy from the final movement of the Symphony No 9 by Ludwig van Beethoven. "It is the European Union anthem and better sounding than any individual country's."

Food, South Indian vegetarian but also Shanghainese xiaolongbao (small dumplings).