Xu Bing's China bursts forth in artwork

Creator of Phoenix art project: 'Cultural DNA elements ... are deeply embedded'

The Falk Auditorium, the main conference room at the Brookings Institution, is a venue where contentious issues such as maritime disputes in the South China Sea, a coup attempt in Turkey and a recent talk on whether the US is losing China to Russia are aired.

On Tuesday, the full house was intrigued by a panel on Chinese contemporary art.

Xu Bing, well known for his Phoenix art project on display in New York City two years ago, recalled that when he first came to the United States in 1990, he kept his old art work in a suitcase and dared not show it to people.

But soon he realized that those art works strongly reflect his unique cultural DNA, which blends influences from Chinese traditional culture, early socialist China, China's reform and opening up, and his contact with the rest of the world.

"These cultural DNA elements, even if you try to hide them, are deeply embedded in yourself. When needed, they will re-emerge again and help your work," Xu said.

|

Xu Bing, a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, discusses his artwork during a panel discussion at the Brookings Institution in Washington on Tuesday. In the background is a photo of his famed Phoenix.? Chen Weihua / China Daily |

After spending 18 years in the US, Xu went back to China in 2008 to serve as vice-president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing, where he is now a professor.

The big screen in the room showed his creation of square word calligraphy. Only careful observers will find that they were actually one-block words made of English letters bent to the shape of Chinese characters.

Also included is a silk banner Xu created for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The seemingly four Chinese characters actually are English words "Art for the People", a slogan by Chairman Mao Zedong.

Xu admitted that the words have a deep impact on him, noting that a major problem of contemporary art is the gap between the art and ordinary people. "It has played a vital role in my work of global contemporary art," he said.

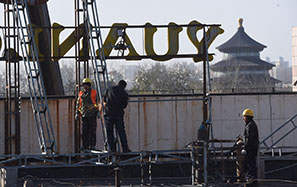

His popular Phoenix project includes a pair of two phoenixes, 100 feet and 90 feet long. They were created largely out of construction debris and tools he salvaged from worksites in Beijing. The work took two years, compared with four months as previously planned.

Xu felt proud that some people see his works as traditional while others believe they are contemporary.

Fan Di'an, president of CAFA, described the development of Chinese contemporary art in past decades, evidenced by the mushrooming art museums.

The transactions of Chinese contemporary art now account for 18.5 percent of the global total.

He said that more Chinese contemporary art should be introduced to the world. "So there is still deficit of art exchange on the part of China," he said, citing the many exhibits of Western artists in China.

Xu felt proud that some people see his works as traditional while others believe they are contemporary.

Fan Di'an, president of CAFA, described the development of Chinese contemporary art in past decades, evidenced by the mushrooming art museums. The transactions of Chinese contemporary art now account for 18.5 percent of the global total.

He said that more Chinese contemporary art should be introduced to the world. "So there is still deficit of art exchange on the part of China," he said, citing the many exhibits of Western artists in China.

Jan Stuart, curator of Chinese art in the Freer and Sackler Gallieries in Washington, worked with both Xu and Fan in her previous capacity as Keeper of Asia in the British Museum in London. She praised both for their contributions to contemporary art.

Stuart pointed out the Western-centric misconception that China is being forced to conform to Western traditions in the global art market. She said that if there was a Western-centric global art market in 1980, the beginning of the global art market was in China 10 centuries ago.

"And the Chinese global art market started through ceramics was the greatest first global commodity, and it took painting and shape and glaze technology aesthetics all over the world," Stuart said. "So we have borrowed from China many times in our traditions."

Stuart dismissed some Western critics for focusing only on a few Chinese artists, for what she called political reasons. She praised Xu for his work and Fan for bringing Chinese arts to the world.

She called Xu the most dangerous artist "because he doesn't look at whether you are Chinese or American, or whatever you are, he questions your ability to interpret what you see".

"He actually says, perhaps everything you see is an illusion, perhaps you haven't really thought to the bottom of it," Stuart said.