Suicides reveal rural seniors' desperation

Many take their own lives so as not to be a burden on their children, according to one researcher, as Tang Yue reports

Editor's note: This is the last in a recent series of reports by China Daily looking at the lives of elderly people, the problems they face and ongoing efforts to improve their standards of living. Also, the story aims to raise awareness about suicide prevention among seniors as Sept 10 is the annual World Suicide Prevention Day.

Fang Fengying lost her only child in 2002, when her 19-year-old daughter fell to her death from a four-meter high ledge in the suburbs of Beijing.

Less than a decade later, in 2011, Fang's husband died of esophageal cancer. "It was even more difficult than losing my daughter because I was left totally alone in the world," the 63-year-old recalled.

"I was fully prepared. I was ready to jump to my death at any time."

Fang began to see things that weren't there. Once, in a confused state, she mistook a woman on the street for her daughter and tried to convince the stranger to come home with her.

She was depressed, but fortunately two of her friends noticed her behavior and took her to a hospital for treatment.

Though still on medication, Fang said she has found a new partner and can enjoy life again now. But not everyone is so lucky.

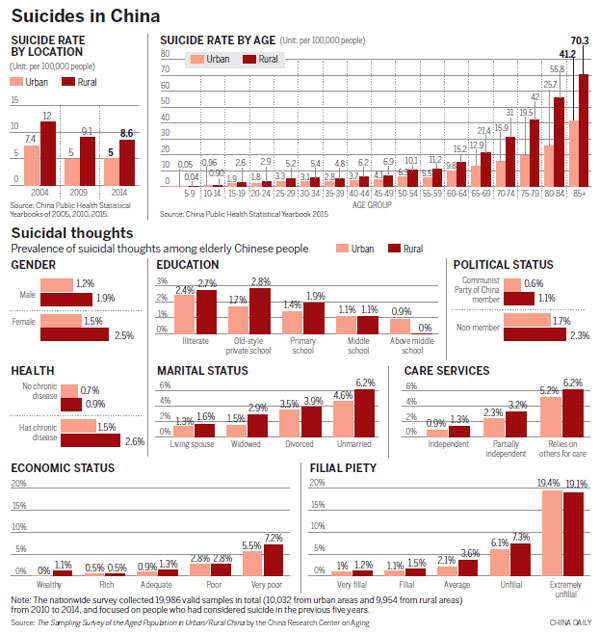

According to the World Health Organization, China's suicide rate dropped from 19.4 per 100,000 in 2000 to 7.8 per 100,000 in 2012, when the global average was 11.4 suicides per 100,000. Yet figures from the China Public Health Statistical Yearbook suggest that suicide rates are much higher among the older generation, especially in the countryside.

According to the data, in 2014, the suicide rate among 55 to 59-year-olds living in urban areas was 5.53 per 100,000, rising to 41.2 per 100,000 for those age 85 and older. In rural areas, meanwhile, the rates for the two age groups were 11.2 per 100,000 and 70.3 per 100,000, respectively.

However, high suicide rates among the elderly are not unique to China, according to the WHO report.

Li Xianyun, deputy director of the Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center, attributed the phenomenon to multiple factors such as deteriorating health, loneliness and low self-worth.

According to Mu Guangzong, a demographics professor at Peking University, seniors in China are particularly vulnerable due to the former one-child policy, which led to families with fewer children, and the limited scope of social services that cannot keep pace with a rapidly aging society.

Statistics published by the National Health and Family Planning Commission in 2015 showed that half of China's senior population, or more than 100 million people age 60 or older, were classified as "empty nesters" as their children had left home.

"The whole of society largely ignores the elderly. Textbooks have 200 to 300 pages on child psychology and only two or three pages when it comes to the elderly," said Lin Xue, who majored in psychology and is now a psychological consultant with the Beijing-based "Love Elderly Hotline".

The service was launched a decade ago after its founder, Xu Kun, prevented a desperate widower from committing suicide and realized the scale of the problem.

"For those who lose their partners, the first 18 months are pretty dangerous and for those who lose their only child, they need attention and care for their entire life," she said.

In addition to the hotline service, which the government funds, Xu also organizes meetings and outings for those who have lost loved ones, sponsored by US multinational Johnson and Johnson.

"We escape the festivals together. Those times when families would usually be gathering are always the hardest time for them. Instead of indulging in sadness, why not go on a trip?" she said.

The urban-rural gap

The significant difference in suicide rates between seniors living in urban and rural areas is a uniquely Chinese problem, according to Li from the Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center.

She attributes it to the differences in living standards, and medical and social services that exist in China's countryside versus its cities.

A study by the center found that 63 percent of those who took their own lives, and 40 percent of those who attempted to, had a mental disorder. The rates were even higher among people age 55 and above, Li said.

"But many people in rural areas still don't see mental problems as a disease and, even if they do, they lack the resources to get treatment," she said.

Yang Hua, a researcher with the China Rural Governance Study Center at Huazhong University of Science and Technology, has a different theory.

Based on field studies he has carried out since 2008 in Hubei, Henan, Hunan and Shaanxi provinces, he believes there are four main reasons for suicides among the elderly in rural areas: boredom, self-interest, altruism and desperation.

At one extreme, Yang said he discovered that half the elderly people who took their own lives in Jingshan county, Hubei province, did it for their families.

"When they are diagnosed with a disease that is incurable or the treatment is very expensive, they sometimes just choose to end their lives themselves; they don't want to be a burden on their children," he said.

In other cases, elderly "empty nesters" were left destitute after they became too old to farm, because farmers were not included in the national pension system until 2009.

Today, most farmers in China can receive at least 70 yuan ($10.50) per month from the central government plus a separate sum of money from the local government, which varies from place to place.

"It's not much, but in some poorer places, it gives hope to those who are struggling," said He Xuefeng, director of the China Rural Governance Study Center.

Yang, from the China Rural Governance Study Center, warned of the possible knock-on effects of urbanization on seniors in places like Henan and Hubei.

"Their children have left home and live in the city and because house prices are rising rapidly and the cost of raising children is so high, these children neglect their parents left in the countryside," he said.

"It is a very serious problem in a fast changing society, but still remains largely ignored."

Wang Zehua contributed to the story.

Contact the writer at [email protected]

|

|